Mary Akers: Thanks for agreeing to be interviewed, Ru. I found your essay (In All Things, Absent) about the loss of your mother to be so moving. Mother-daughter relationships can be fraught with conflict, can’t they? Even in the most loving relationships. A huge question, but, why do you think this is?

Ru Freeman: I think the relationship between mothers and any child is fraught. Physically bringing a human being into the world makes the whole world a woman’s concern; once a small human incubates in one’s body, the boundaries between what is felt within and what is happening outside dissolve. A woman becomes involved in creation, evolution, metamorphosis, all of those big things. How can she then disassociate from the product? Because in a very real sense, a being that was once physically a part of her is now wandering abroad! How do you stay in one place and nurture the happy but also sometimes deeply unhappy wanderer? So, yes, fraught.

The relationship between mothers and daughters are conflicted for all the best reasons – the need to distinguish a daughter’s version of mothering/creation from her mother’s approach, the desire to be somehow original as you go about being a woman in the world when so much of what we do as human beings is timeless and requires no change. So we turn to the way we cook, clean, do or do not coddle children, do or do not tolerate life’s injustices – particularly as they are meted out to women by men – choose to work outside the home or not, even how we dress. In Sri Lankan culture, too, a daughter (or son), remains a child. Then they grow up and have children of their own and I think it is hard for a mother to see that and assume that their child is going to be fully able to take care of little people. The possibilities for conflict? Endless!

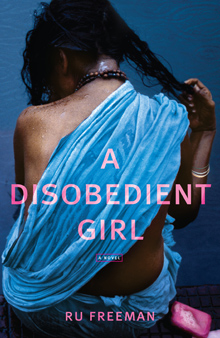

MA: Your gorgeous novel A Disobedient Girl wrecked me in the very best possible way. The relationship between Latha and Thara, the two young girls who grow up in the course of the story, struck me as another meditation on the complex ways that women can simultaneously love one another and undermine that love. Would you care to comment on that?

RF: I love women. I love their multi-faceted way of existing in the world and I want to gather them in my arms and keep them safe from everything! As I raise my three daughters now, I am often struck by the ways in which they pick up the obvious put downs that popular cultures inflicts on women. You know, the bitchy, catty words we are taught to use on other women. I find myself saying “don’t dress like a road tart,” while also defending the people one or the other may describe as being one! I tell them to beware of the temptation to call a beautiful girl a tramp or a slut just because of how she looks, and I tell them unless you actually saw a girl-friend engaged in some sort of unsavory behavior, don’t repeat the gossip.

One of my favorite books is Toni Morrison’s SULA. I think that novel encapsulated for me the way that women’s relationships are fractured by the introduction of men. I grew up with brothers, longing for sisters, and so almost all my most meaningful friendships are with women. They are the ones I feel I must trust even when that trust is betrayed. I am always deeply hurt when that happens, I find myself literally staggering back thinking “But how could she do that? We are the same.” And yet I have caught myself undermining other women with regard to the affections of men. A part of me would like to believe that women play these games because so many men lack the depth to be more than playthings. And so like cats with foolish mice we bat them here and there and amuse ourselves and, just like the felines, often aren’t even interested in consuming the catch! And part of me believes that the reason we consider it fair game to engage in that kind of behavior with another woman’s man is because we believe that no man is ever worth the end of a friendship with our women friends. But then there’s love. And that complicates what is already so intricate, so complex between women.

If you remember, Latha’s first revenge was not against Thara but Thara’s mother, Mrs. Vithanage, and it didn’t even occur to her that in choosing that particular form of revenge she would be hurting her friend. In writing the story of Latha and Thara, I wanted to explore the parts of them that forgave each other and loved each other no matter what. In the end whatever Thara is screaming at Latha, her real anger – in my mind, I don’t know what the reader thinks – is reserved for Gehan. And in Latha’s mind the real betrayal is also from Gehan. I wanted to go to that place where a woman can find the reasons to explain away the guilt of a woman friend, when she is simultaneously unable to forgive a man.

MA: Yes, I do remember! I thought that was a brilliant touch. It strikes me that the setting of A Disobedient Girl is so important to the story, as well.

I recently had the chance to visit the Georgia O’Keefe Museum. She spoke (in a film clip) about “the power of place,” and the first time she saw New Mexico and knew it was “a place where she could breathe.” Do you have a place like that in your life? Could you tell us a little bit about the inspiration that place gives you as an artist?

RF: The place that I have felt happiest at is at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Ripton, VT. In fact for years the background on my computer was a scene of the campus, with two empty Adirondack chairs facing the far mountains. Going there has been intensely affirming of all the parts of me that I like the best – the writer, the people-person, the dancer, the performer, the cross-cultural permanent foreigner, the quiet walker, even the socialite. In being all those things, I also got to set aside my biggest responsibility, being a mother, which is so full of fatigue and difficulties and drudgery that it is often hard to remember the grace and joy of it. For a short time I get to open all the hidden parts of myself and let the fairies and the goblins that live inside, out to play and get some oxygen. Bread Loaf rejuvenates my soul in a way no other place has ever done.

When I think of writing, however, something I rarely do at Bread Loaf, I think of Yaddo where I finished my second book. The immense quiet of the place during the hours that are usually the loudest outside its gates freed me to write non-stop and without a single moment of questioning – my work, my words, my ideas, my themes, my story, myself, anything. I derived great comfort from visiting the grave of Katrina Trask, and sitting there in contemplation of life, death, the vision that enables someone to imagine a place such as Yaddo is, and the generosity of spirit that made it possible to see beyond grief to gift. Even now I can close my eyes and go back to that time, and from there to the time before when she was still alive, her children were still alive and then back closer to when they were all gone and what she had left was a broken but remarkable heart. She chose to affirm life. It’s a great lesson and one that I learned there.

MA: You have strong convictions and have done a great deal of work in the areas of humanitarian assistance and workers’ rights. Could you tell us how (and if) those issues enter your creative work?

RF: Well, I think for most people who are involved in these things, it is a way of looking at the world, a way of existing. These issues with which I’m preoccupied all the time inevitably seep into my writing. I am concerned with “little” people, “ordinary” lives and very personal struggles. In my first novel, for instance, the matter of finding safety – literally, a roof over their heads, food – is the entire story of Biso and her children. And the matter of actualizing the self despite the way that her social status made Latha almost invisible was her story. Both tie into my interest in the social injustices that we, the privileged, are trained to airbrush to serve our own purposes.

MA:What role do you think politics has in the creation of art? Can/should good art be political?

RF: I think that every personal choice is a political one that impacts other human beings. Unless you are living off the fat of the land in the wilderness and even then – I mean, you’d have questions regarding who owns the land, what is in the water, etc. etc! And art, particularly art that involves the written word, deals with personal choices. The trick is, I think, to figure out how to create narratives, whether fictional or non fictional, that reflect but don’t necessarily comment upon the politics of choice. If it can be managed, it is, to borrow our old hackneyed workshop dictum, far more transformative to “show” a reader what is before them than to to “tell” them how or what to think about it. To allow the reader to absorb the story, consider the implications and come up with a response that they can own, that is the only way that someone like me can effect social change through the creation of art. I think though that in the end, the subtlety and compassion in that kind of writing is far more useful than what I do the rest of the time: browbeating people into submission with the spoken word, debating and arguing them into the ground!

MA: What did you think of the illustration that Morgan Mauer designed for your piece? Did you find any special meaning in it?

RF: I was intrigued by the way Morgan had depicted the treasure box of books. I didn’t have many books when I was growing up, but my family, my mother in particular, was the receptacle of stories. My first poetry, short stories, plays, all these things came to me in the voice of my mother, listening to her as she taught other students and, later, one of my older brothers and eventually me. I found it interesting also that the colors that Morgan had picked were colors that my mother loved – lilac and pink and green.

MA: And finally, what does recovery mean to you?

RF: In Buddhist philosophy, we don’t necessarily recover from loss or grief or hardship, we absorb those aspects into our lives. So recovery for me means living with a different awareness, of the consciousness of finite time. It also means looking more deliberately at what I still hold in my hand, knowing that it won’t always be so. It means understanding that all that I see before me will outlive my many and daily attempts to impose my will upon it. When I think about my mother and I want her back, I want to smooth away the rough edges in our relationship, tie up the loose ends, explain everything. As a Buddhist, I am comforted by the sense that she is, or will be, somewhere else in the universe, and that through samsara we are reborn among those with whom we have unfinished work. She and I, we were a work-in-progress, and in a way, while I wish that she is spared of the suffering that accompanies human life, I am also soothed by the sense that we will meet again.

MA: Thank you so much, Ru, for speaking with us today. It’s been a great discussion. And for readers, who wish to read more of Ru’s wonderful writing, visit her blog, which is also part of her gorgeous website.

Pingback: “In All Things, Absent” by Ru Freeman | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal