Dustin Hoffman: Hey, Brandon, it’s a pleasure to interview someone I’ve spent so many nights drinking beers and discussing writing with. Now I have you where I want you, and you can’t just laugh off my questions with a joke about the literary continuum between Kafka and Looney Tunes. This time it’s serious. I’ve been reading your work in workshops and outside of class for years. You started writing mainly short fiction, but essays like “Paul Maidman ~ Banana Man” get a lot of your focus now. Could you talk a bit about how your process for approaching an essay differs from that of a story? What draws you to the essay form?

Brandon Davis Jennings: First it’s an honor to have this opportunity, to be interviewed by a writer I admire and have this interview published at a magazine that I respect. I’ll avoid all continuum references and get right to your questions. I’d be a liar if I claimed that most of the stories I’ve written weren’t rooted in my own experiences—good and bad. And I do consider myself a storywriter first. But the essay form is something I’ve been drawn to because the constraints it places on the narrative provides me with focus—sort of the way a poet might write a Sonnet in order to free himself from thinking about form. A lot of these essays, including this one about Paul, have things that I can’t shove out of my head; memories can become so distracting that in order to get past them, I have to write them and write them as truth. Simply put, I write these essays so that I can make room in my head for the stories I can’t tell yet. But I also feel the need to present these essay with all the care and attention that I would give a work of fiction.—Paul deserves nothing less than my best effort, and I wouldn’t want to present anything less than my best to an audience. And when it comes down to it, these essays are just the way I narrate my own life.

DH: Throughout this essay, we find inserts of dialogue that take place outside the reflective scenes. Arguments emerge through these excerpts that often strike at the very telling of the essay. What’s your drive to include these? How do you see them as contributing to the overall effect?

BJ: The internal discussions you’ve mentioned are something that happened by accident at first, and they’ve continued to show up in my non-fiction. Sometimes they are my conscience; sometimes they are complete artifice in order to get a laugh. Sometimes I’m not sure what they are until long after they’ve been written. As far as contributing to the overall effect, all I can say is that they exist within the essays because these essays are written by an older (and potentially wiser) me who feels comfortable making fun of himself and criticizing himself for being foolish or naïve or a jerk—for being human. There is always a voice in my head commenting on every thing I do; it’s like my conscience is work-shopping every choice I make (something that’s been going on for as long as I can remember); some of his comments are valuable, and sometimes he’s just talking to hear the sound of his voice. Maybe that’s a condition I should seek treatment for. But I’ve lived with it this long, so I won’t.

DH: Time becomes unhinged in this essay. We start with the banana show and then take big leaps to moments before and after. Rather than linear chronology, the essay scatters time into modular sections. How do you approach time when writing, and in this essay, how did you find the sequence that works best, as in, for example, framing this piece with the banana show?

BJ: Because I’ve been a literature student for a while now, it’s easy to write something and then look at it in retrospect and make up an answer to a question like this. I could say that time is unhinged in the essay because I want it to reflect the way that the memories came to me. But I think a more reasonable explanation is that I wrote this with the frame of the banana show because it was about Paul, and he was The Banana Man to me before he was anything else, before I knew what the name meant. And although I could have just come right out and said why and how he earned that nickname, I wasn’t ready to say how it happened until the final paragraph. Certainly suspense played a role in my decision to reveal all the details at the end, but it wasn’t the most important factor. I didn’t intend for this to have a big twist at the end; that kind of narrative is rarely something I find worth writing or reading. But I needed the space in between when I introduced Paul in the essay and when I explain how he earned his nickname to prepare myself to deliver it honestly to the reader. It was like a written representation of the space I often need between myself and an event in order to write about it artfully. Although I do think it’s possible to analyze these kinds of decisions in retrospect, I didn’t think about any of this until I’d had the essay drafted. I’m a sweeper, as Vonnegut put it. So the essay often has to be on the page before I know how it needs to be written.

DH: There are some really funny moments in this essay, and then some moments that make me laugh and then make me feel bad for laughing. How do you approach humor?

BJ: There is little about life that isn’t funny to me; it borders on sick. This year my fiancé asked me to play in an annual softball game, and I don’t play sports anymore (partly) because I don’t want to injure myself in pointless competitions. I played because I knew it would make her happy, and then I pulled my hamstring. I was angry in the moment, but things like that have happened to me my entire life, and if I didn’t laugh at them, I’d be even less fun to be around. So I don’t think I approach humor; humor approaches me. And if you feel bad for laughing at something I’ve written, then that has the potential to teach you something about yourself and about me. But I’m also a firm believer that if you understand exactly why something is funny, then it isn’t as funny as it could be. I won’t risk trying to explain that. I think that Craig Paulenich’s Goat Man poems achieve something along the lines of this; he blends horrifying and hilarious. A goat man is funny in a poem; a goat man is not funny when he’s reading a poem to you.

DH: In the last sequence of the essay, the narrator says, “Eulogies are terrible—almost without fail.” Yet, this essay leans in that direction at times. Perhaps even this statement denying eulogy draws my sentiments in that direction. How is and isn’t this a eulogy? How do you approach writing about the dead, honoring them and remembering them through what we might initially imagine as unflattering vehicles?

BJ: I like how you call me “the narrator”. That makes me feel like I’ve achieved a level of dream state in the essay, and that hopefully when people read this they forget that they are being told facts and just enjoy the ride of the narrative. But this was one of the most difficult essays for me to write because it feels like I’m taking advantage of a tragedy. Maybe that’s foolish, but it’s how I feel; so maybe I’m a fool. But when I heard Paul died, I read a few articles that talked about him, things that claimed he was all these things and that had he lived, he could have been all these other things. I didn’t give a damn about what he could have been because he was a great guy to me when we were stationed together, and even though he’s gone now, that is all that matters. If I died in ten minutes I wouldn’t want people to make me out to be some potentially amazing person. I want people to remember the great moments we had together and the shitty ones too. This is a eulogy for Paul, but it’s also a thank you, for giving me the inspiration to talk about things that I have been afraid to talk about for a long time. Writing this essay opened up a vault I’d locked down for a couple decades.

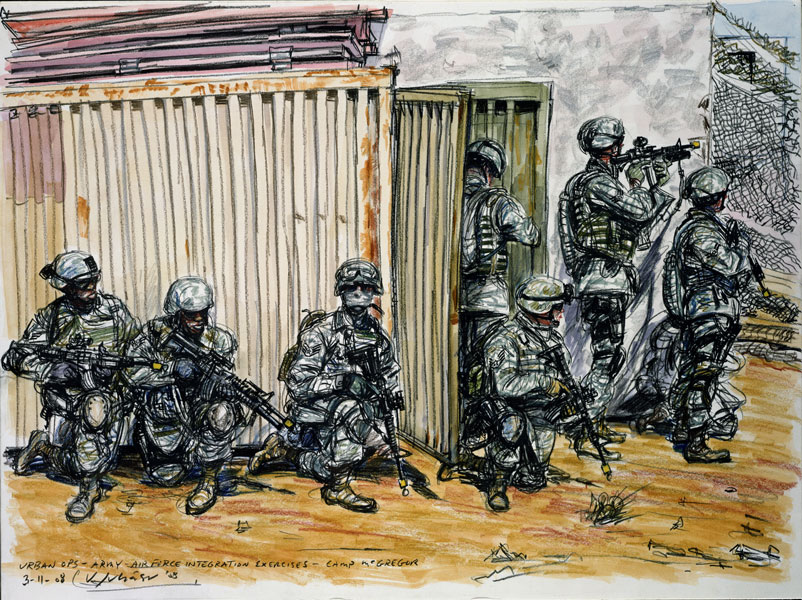

DH: What authors inspire you when writing about the delicately harsh themes of military life?

BJ: I can answer with Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, Tim O’Brien, Bruce Weigl—I could go on for pages probably. But I don’t read them or feel connected to these writers because I believe military life is any harsher than many of the kinds of life that people live. I think military life is romanticized a lot, and that’s something the above-mentioned writers work against; they aren’t recruiters—at least not on purpose. And I believe that having some kind of emotional pain that you can’t shake off is one of the draws of the military. People want their lives to matter and sometimes they think the best way to go about living a worthwhile life is by seeing how it feels to watch your friends explode. I’d be surprised if the number of people who signed up for EOD didn’t spike after The Hurt Locker came out, and I’d be a liar if I said there weren’t days that I wish I’d have done more while I was enlisted. Usually that only happens when writing is a challenge. I’m glad that I have all my parts and that I never saw anyone die.

DH: I’ve been enjoying reading archives on r.kv.r.y., and your essay fits the theme. What does “recovery” mean to you?

BJ: This is probably going to sound corny, but for me recovery is getting out of bed each day and being me. Some days it’s easy to recognize the things I should be grateful for, and other days it’s not. If I woke up one day and felt recovered, I don’t know what I would do with myself. There are always things pushing against me; recovery might be pushing back. And the only way I know how to push back is with words. That’s something that writing this essay about Paul helped me to understand more clearly.

Dustin M. Hoffman spent ten years as a house painter and drywaller before getting his MFA in fiction from Bowling Green State University. He is currently working on his PhD in creative writing at Western Michigan University. His work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Blue Mesa Review, Puerto del Sol, Artifice, Cream City Review, Copper Nickel, Witness, Palooka, Southeast Review, and Indiana Review.

Pingback: “Paul Maidman, Banana Man” by Brandon Davis Jennings | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal