Denice Rovira Hazlett: There are few people in the world as mature and balanced and loyal and adventurous as Leslie Nielsen. She walks solidly along this shore and yet, at any moment, will venture confidently into the swelling and crashing waves to meet spilling and surging breakers alike with the same sweet mixture of erudition and acumen, always allowing her feet to come fearlessly in contact with all matter of benthic life. She is a scholar, a poet, and, I’m so honored to say, a dear, dear friend. Her piece, Still Shining, is a halcyon snapshot of those untroubled childhood moments just before slipping into the violaceous and pelagic place of sleep. I’m happy to have the opportunity to interview her today.

Leslie, there’s a theme of water in this piece–the word choices of “splash,” and “drift,” talk of fish and currents and, of course, the sister calling for water. The color choices, too, of green and lavender. Can you talk a little bit about those word choices?

Leslie Nielsen: I have a long-ago poem that explored night and sleep like a long underwater swim until morning casts awareness onto a gritty beach. Until this question, I’d forgotten about it. I suppose I do think of sleeping as submersion into a different sort of world than the waking one we leave behind.

Also, before each of my daughters was old enough to choose her own room color (and they’ve chosen vibrantly) I leaned toward cooler colors in hopes of calming sleep. That way of thinking, and the poem’s unrealistically quiet and steady slide into sleep are an idealized and loving vision for bedtimes that are often bumpier and, at our house,

usually very entertaining.

DRH: Your piece begins with “long from now you will remember,” which comes all at once as a charge and a hope and a personal memory. Why was it important for you to capture this moment? And what moment does this equal for you in your bank of childhood memories?

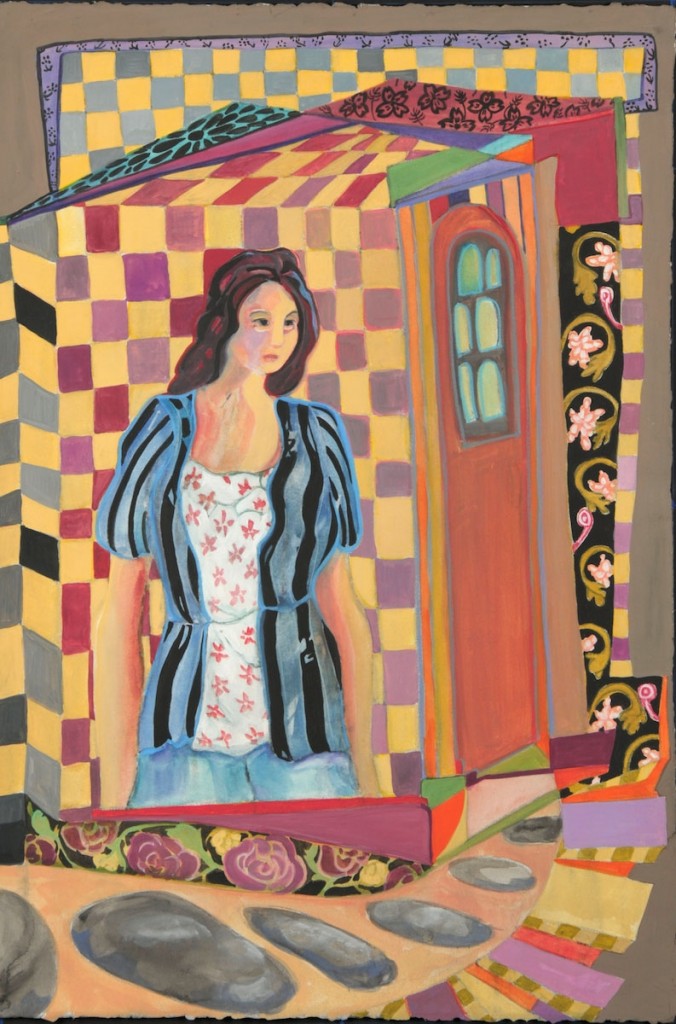

LN: In conception, the poem was about my two youngest daughters, but then the art chosen to accompany it in r.kv.r.y. slid me to a place where they were grown and in the long-from-now time. I think, as I mentioned, parents have idealized versions of what childhoods can be, and then in contrast, we live with our children through the details of every real day. At some point, each young adult composes the narrative of her own life and what it’s meant so far. My oldest daughter’s going through that now and it’s amazing how much her version differs from mine! I have a hope, though, that the quieter, ambient, inarticulate moments surface now and again as defining the texture of the childhoods they lived. But you’re also casting me backward in time through my own narrative, and I guess I end up in our old farmhouse, in bed, tucked in but not asleep, when we had company, hearing adult voices and all their music but none of the words—exactly the sort of texture I’d want my daughters to have stored away. That room was lavender, by the way, until I chose my own vibrant personality colors!

DRH: Is there a particular part of this piece that arrived to you like a wave, something welcomed and unexpected that made it all slide into place?

LN: More like a series of waves. Unlike so much of my writing which more resembles patchwork after being assembled from a chaos of inspirations and labors, this one arrived by patience, a few words or a line at a time on one evening. It underwent shockingly mild revision, also entirely unlike my usual upheaval. By the time the lines were arriving at “the moment / you won’t remember” I knew exactly where I was going.

DRH: I know line breaks are very important to you. Tell me how you chose your line breaks and how they affected the piece.

LN: There’s some balance of tension and flow going on, a slight lift at the end of each line. In the manuscript I’m working on, there’s a lot of attention to the pentameter line—disciplined adherence so I can learn to make it work for me without being mechanical and an equal dose of violation to keep each line dynamized. This poem, again, arrived gently on its own, so there wasn’t much scanning, but as I look back at it, I can see that all the exercising in meter is starting to pay off with a natural but rhythmic line.

DRH: This piece is so much about a sense of place, an environment, a cradling of warmth and trust and safety. Tell me why environment has so much impact on this piece.

LN: Annie Dillard opens An American Childhood with a sequence of spiraling-in /images, then makes the audacious claim that when every other memory has left her, she’ll remember the topography of the hills surrounding Pittsburgh, where she grew up. Whether because of her words or in verification of them, more and more I realize that the experiences of my childhood, map my awareness and preferences far less than does the farmland around Seville, Ohio. The barn, fruit trees in the pasture and orchard, various dips in the fields that flooded and froze over so we could skate around corn stubble on de facto lakes, coal furnace clinkers filling low spots in the driveway, excavation for remodeling, the huge garden. Yes, there was my family, but sometimes I think my sense of self connects to the place more than the people.

Children are their senses, and places, while they reflect the temperament and condition of the people who establish and tend them, don’t leave and go to work; they don’t lose their tempers or forget things. A place can’t really disappoint, and that’s a sort of safety for the senses. The two scarves, great big sarongs, really, that are mentioned in the poem have proven to be universal playthings—they’re costumes, tents, sacks, lines for practicing the limbo, and I drape them over curtain rods in the summer to darken bedrooms. I don’t actually think my girls should trust things more than people, especially me, but when I’m not there, their environment should bring them beauty.

Denice Rovira Hazlett has published more than 150 feature, travel, profile and short fiction pieces in publications like Farming, Ohio’s Amish Country, the Mennonite and more. Her online column for Larry’s Music in Wooster, Ohio, called Liner Notes, features local folks in the music field. She has written about diverse subjects, from the 2012 NCAA basketball Final Four® floor to The X Factor finalist Josh Krajcik and has tackled the tough issues like eating disorders and childhood sexual abuse. Denice currently writes short fiction that focuses on choices and regret, or the lack thereof. She lives in Charm, Ohio with two rescued pit bulls, a coon hound, a Jack Russell terrier, and a goofy black lab, all of whom receive lots of love from her five kids and musician husband. Join her at www.denicehazlett.com where she exposes beauty, cracks open darkness, and exhumes hope.

Pingback: Still Shining | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal

Pingback: Still Shining | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal

Pingback: Still Shining | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal

Pingback: “Still Shining” by Leslie Nielsen | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal