Mary Akers: First off, thanks so much for agreeing to adopt our GRAVITY issue and supply your wonderful images to pair with our poems, essays, and fiction. I’m so pleased with how the issue came together. And since I’m starting off with that, I think I’ll go ahead and make my first question on a related topic. How do you feel about pairing images with writing? I ask this, because I’m of two minds. On the positive side, I love connections anywhere I find them. And I love bringing different genres of art together; I feel like the combination of two art forms takes us more places than either one can take us separately. That, said, there is also a danger of one art form informing the other in a way that neither artist intended. Where do you come down on this spectrum?

Wiley Quixote: Thank you – I was happy to be asked and felt ready for the challenge, the timing was good for me.

Pairing images with writing is a welcome challenge. Happily, you offered me two choices – to tailor the images to each piece or to explore the idea of gravity on my own and let you do the pairing from the available shots. My first impulse was to do the former, but really, I had my own ideas and time constraints so I ultimately opted for the latter hoping for the best. I was happy with the results.

I think that the all art is (or should be) by nature dangerous and risky and you have to take the chance that it might fail. That’s part of what makes it pleasing when it works. Pairing an image with writing seems pretty tricky to me – it’s not a script for a movie where little is left to the imagination with the intent of telling that story through images, you’re providing a companion piece to another piece of work, where each has its own merit and form of expression. Given that there were 14 pieces from 14 different authors, I found that challenge on a one-to-one basis too intimidating an approach and it would have felt hubristic to have tried. The beauty of this collection to me was great diversity of expression around a particular theme and I felt like I wanted to be a participant and add to that conversation. In a conversation, the connections happen on their own.

MA: Yes, I agree. Maybe that idea is similar to what you say about art–it might fail, that conversation. But when it works, it’s a boon to both sides.

I have another, somewhat related question. Who do you think “owns” the interpretation of art? Do we, as artists, make our art and then simply surrender our creations to the viewer who then is free to take whatever meaning he or she wants from our creation? This being the “collaborative” notion of art, where the viewer is as important as the creator. Or do you think we, as artists can (and maybe should) expect viewers to recognize and appreciate the meaning with which we imbue our art? How do you think either viewpoint affects the “interpretive ownership” of art?

WQ: On the one hand, I really want the ideas I’m trying to communicate – explicit and implicit – to be executed well enough that they are witnessed, recognized, and appreciated. On the other hand, I only want to take responsibility for communicating it well enough to get the message across but not to fencing in someone’s imagination or hindering an interpretive response. I’m happy to disagree with someone’s interpretation that does not suit my intent, as long as they’re provoked or inspired to make use of their imagination. To me, that’s the dynamism of an otherwise static representation.

I’m inclined to return again and again to the idea of arrest and provocation. We can shape and channel with intention, we can qualify, manipulate, suggest and critique with expression, but we cannot command and dictate impression. What is art without an audience? What is expression without impression? It’s got be both things, and a matter of degrees as to which is the predominant factor in each instance.

“Ownership” implies ego to me. Artists, critics, and viewers can fall into that trap, but art is a living force that rises up from the spring of the muses and seeks a channel and a form of expression for an audience – even if you’re the only audience. We – the artist AND the audience – are the channel and receptacle and, at best, can collaboratively midwife an idea and give it an opportunity for form – it takes both expression to come into being and impression to achieve meaning.

MA: I like that answer. I struggle a lot with owning my old work versus letting my completed work go, so it’s nice to have that feeling articulated.

I love your pseudonym, but I’ve got to ask–and I know readers are curious, too. You’ve given your nom de photog a lot of thought, so I’m looking forward to your answer. Why the pseudonym? Is it for the sake of anonymity? Is it a statement against the NSA? Is it just for fun? Is it a way to say that the creator of art isn’t as important at the art created? Do tell!

WQ: I’m happy you’ve asked this question because I’d like to give the idea some public expression. I do so like to chase roadrunners and fight windmills.

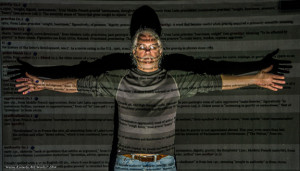

My pseudonym is a compound of the trickster and the fool, and being crafty with your approach is implicit in the name “Wiley.” Obviously, the name is foremost a pun on the familiar character of Wile E. Coyote. The coyote is a trickster figure in Native American mythology and plays a role in their creation mythology. As I recall, roughly, in the beginning there was only water. Coyote and fox where in a boat together. Coyote slept while fox rowed and created the world. Once it was created, coyote woke up and devoured it all. That is the essence of creativity to me. There is a creative aspect and a destructive aspect and the process is one lead by the ambivalent figure bearing those two faces: the trickster and the clever creator – foolish in retrospect, but ultimately the benefactor of all the innovations we come to take for granted. If I have a personal psychopomp for creative expression it is the trickster figure who always makes an appearance for better or for worse.

Then, there’s Don Quixote. Perhaps a tragic and foolish character, but a divine one – the archetypal dreamer: so detached from reality, and so noble in vision. His is the personification of the vivid and creative imagination that performs great deeds in lands far away.

To me the figure of this pseudonym is a personal gnostic demiurge.

The name actually arose as a consequence of being called quixotic and foolish for taking a principled stand years ago about something I felt strongly about (involving contemporary ideas of privacy and corporate and government transgressions against the fourth amendment – long before the Snowden revelations). In that regard, hyperbolic as it may sound, I’ve become accustomed to feeling like a kind of “Kassandra” – a mythological figure who was given the gift of prophecy but cursed to having no one ever believe her. It suits my intuitive nature, my anima. However, it’s not solely about that, indeed, that’s a small part of it, only an impetus. It quickly became part of a larger set of realizations about character and expression and identity – public and private.

I like to think that we are all “Horatios” and “Percevals”, fools everyone. And wisdom is the currency that rewards us for accepting it and living it honestly, sincerely. There’s great humility in that, and great reward – especially, I think, as an artist. You’re performing a service to the muse, not to the ego.

As someone who has long known the experience of the creative personality, but only recently, at a later stage in life, found opportunity for the expression of it, I am constantly hounded by my naiveté, my inexperience, my lack of academic training, and am subject to countless self-criticisms that stultify and smother progress and expression. All this is wrapped up in a dubious identity and self-image. It can be a prison, a poison, a windmill, a coyote.

The pseudonym gives me freedom from all that, and the opportunity to fail forward. I belong to the pseudonym, it doesn’t belong to me. It’s a way of surrendering my ego to the divine character of creation without the trappings of trying to own it. That doesn’t absolve me of responsibility; it’s just taking it on in a specific role distinct from whoever and however I may otherwise see myself. I cannot stress how important and freeing that has been for me as a burgeoning artist these past several years.

MA: I can see that. A sort of freedom from expectations–expectations that come from the world at large, but that also come from within. I like it. It seems very wise–a trickster even unto the self, if tricking is what it takes to create art unselfconsciously (and I think it is for most of us).

What is it about photography that draws you to it? Your images are so expressive. They are like stories all on their own. I know you’ve explored many art forms over the years. How did you arrive at photography?

WQ: I arrived at it by mistake. I bought a DSLR to take quality photographs of my drawings and pastel paintings and to photograph subject matter – I work from photographs. However, I took to photography like no other form of expression I’d taken to prior. To me it contains all the elements of painting, poetry, music, imagination – it’s so cinematic and so expressive of feeling. It can communicate so many ideas around a particular subject in just one click of the shutter. I continue to be amazed by it. It’s like a snapshot of the imagination.

Every photographer wants to tell a story. I find that, for the most part, the photojournalistic approach is too much like prose; I prefer poetry. So I’ve settled on the poetic narrative as my preferred form. Hopefully, it will continue to evolve in both style and expression.

MA: The poetic narrative. Nicely put.

Every artist I’ve ever met has a “second choice” option for their professional pursuit, creative or otherwise. What would you be doing if you were not doing photography?

WQ: Currently, photography is not a professional pursuit for me – I pay the bills with a full-time corporate job. However, my creative pursuits are dominated by photography right now. What would I be doing if not for photography? I don’t know, sulking? Is that a career path? 😉

I think outside of artistic expression it’d either be something in the humanities/people sciences or something without responsibility so that I could travel and experience life, living and the environment. I never want to live for my job; I want a job so that I can live. If I could have both, that’d be great, but I’m not sure it’s possible for me.

MA: Oh, I feel like I’ve known a few professional sulkers over the years.

And speaking of professional sulkers, who are your favorite writers?

WQ: In no particular order, for fiction, Mark Twain, Kurt Vonnegut, Tom Robbins, Umberto Eco, Philip K.Dick, Edgar Allan Poe. For nonfiction, Carl Jung and several of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd generation Jungians; Joseph Campbell, Alan Watts, Mircea Eliade. And for poetry, Galway Kinnell, Rainer Maria Rilke, Adrienne Rich, Denise Levertov, Mary Oliver, Pablo Neruda.

And just about any set of myths and fairytales I can come across.

MA: Oh, me, too. Myths and fairytales are wonderful sources of inspiration.

I’ve really enjoyed this interview, Wiley Quixote. Thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts with our readers. I’d like to close us out with one final question, if you don’t mind. What does “recovery” mean to you?

WQ: My experience has been one of self-discovery, determination, self-reliance, and the search for meaning; consciously and conscientiously accepting the path of Individuation; becoming; being; continually sloughing off old skins; adapting, creating.