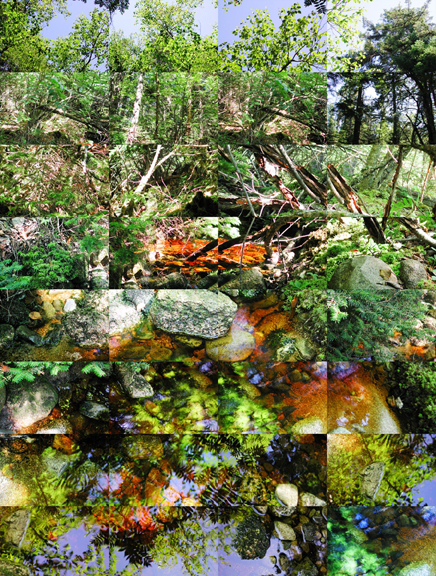

Photo Collage by Matthew Chase-Daniel, 2010.

(See also “Garnet” by Anne Colwell.)

When I was a girl, my father played paper dolls with me every evening after work, and when he cut out the dresses and hats for my little paper girls, he worked cautiously around their edges so they’d be just right. His eyebrows bunched together like two hairy caterpillars. His scissors closed slowly, millimeter by meticulous millimeter. He worked like he wasn’t a New York taxi driver who shared his cab with his terrible older brother and two other Russian men in our apartment building who smelled of gasoline and borscht. He worked like this was his living. He was a paper tailor—and a good one.

I was careless. Too eager to get past the tedious preparation and down to the business of playing. I sliced through an abdomen without looking, or cut off a sleeve. And when I realized what I’d done, I’d collapse against the kitchen table and wail. (I was an excitable child. This was before I learned too much emotion was a disadvantage to survival.)

“Zolotse,” my father would say, his hand on my back. “My gold. Don’t despair. You’ve done nothing that can’t be undone.”

With those reassurances in mind, I’d push myself up from the table to watch him repair my mistake. Because he was not just a paper tailor. He was also a paper surgeon.

He’d mend the wounds with precisely measured bits of scotch tape bound to the backs of the dresses so the stitching would be invisible. When he was finished, they looked as good as new. He was a paper miracle worker.

My mother watched us from the stove where she prepared food to satisfy both of their palates. Hot and sour soup for her, whose chili oil made my father’s eyes water just from sharing the same room as its powerful essence, and Olivier salad for him, a far blander mound of hardboiled egg, peas, and potato slathered in mayonnaise. Then there was always a third dish, one they could both sample: sautéed carrots and beets coated in soy paste. I still don’t know if this is a traditional Chinese dish that happened to incorporate elements of my father’s Russian heritage, or if my mother invented it, after she listed herself in a catalog, agreed to marry a man she’d only seen in a photograph, arrived in the United States two years before I was born, and was relieved and so very grateful to discover she could love the stranger that would be her husband. Grateful to be a wife in America, to be cared for. Grateful enough to cook and eat beets.

“You spoil her. You fix her mistake over and over. She never learn. She never do well herself.”

“You’re right, my love, lyubov moya,” my father answered. “Of course you’re right.”

But he was my paper friend. He continued to fix my mistakes, over and over again. Until the day he died.

Uncle Yegor moved from his apartment into ours the day after my father’s funeral. I was fourteen then. “Ivan wouldn’t want you alone,” he said. “I’ll watch over you. Keep you safe. For my brother.”

He slept on the couch that night, and the night after that. When he was still in our living room a week later, drinking Moskovskaya out of my mother’s porcelain teacups, she said, “Yegor, you been so good to us. But you don’t have to stay here no more. We’re fine. I have Mei-Li and she have me. We do okay.”

I watched from where I was doing my homework at the kitchen table. I knew she wanted him out, but was tiptoeing around everything she’d learned. Family honor. Patriarchy. Meekness.

His stare didn’t waver from the television, where the American soccer team struggled against South Africa. Yegor loved to see Americans lose. “I’ll stay,” he said, his voice gruff, almost threatening. “It wouldn’t be right to leave two women on their own.”

My mother gripped her hands at her waist and smiled in a way that scared me. “No, it’s okay. Really. We be fine. Mei-Li is smart girl. And I’m strong. We take care of each other. And you live close. If we need anything, we find you in no time. But you can go home. Don’t be uncomfortable for our sake.”

His gaze slid toward her. The darkness in his eyes made me put my pencil down. “Now Fan, you don’t sound very hospitable.”

My mother chuckled and shook her head. “Oh no. You misunderstand.”

Yegor shot to his feet and whacked my mother upside the head. It wasn’t forceful, but the sudden cruelty of it caused me to gasp. “Don’t you talk back to me. If I say you are being inhospitable, you are being inhospitable,” he said, and then he returned to the game as if nothing had happened.

Violence in our home was so foreign, so strange, neither my mother nor I knew how to react. I couldn’t see her face from where she was standing, but her body was rigid. After a few frozen moments, she turned on her heels, walked down the hall, and closed her bedroom door behind her. The announcer’s voice hummed in the background, but I couldn’t focus on his words. I could hardly even breathe. Yegor didn’t look back at me. He sloshed another helping of Moskovskaya into my mother’s teacup, one of the few items she’d brought with her from China, and when the American team scored a goal, he screamed, “Otva`li, mu`dak, b`lyad!” and hurled the cup against the wall where it smashed.

As I brushed my teeth that night, he walked down the hall and into my mother’s room. The brush stilled in my hand. I caught a glimpse of her sitting on her bed, a photo album open in her lap. When he appeared, her eyes widened in surprise, and perhaps in fear, but she said nothing to stop him. He closed the door.

Instead of going to bed, I gathered the shards of my mother’s teacup and laid them on the kitchen table. As Yegor’s grunts and my mother’s whimpers drifted through the walls, I hummed to myself and tried to glue her precious keepsake back together. But this time what was done could not be undone. It had been broken into too many pieces to fix.

~

If I ever have a daughter, I will give her a male name. Something like Jaw-long, meaning: like a dragon. Boys get names like that in my mother’s country. Jianjun: building the army. Lei: thunder. Huojin: fire metal. Yingjie: brave and heroic. Girls are defined by their grace, their compliance. Baozhai: dainty and loving. Luli: dewy jasmine. Renxiang: benevolent fragrance.

My name, Mei-Li, means beautiful. But what good did beauty ever do me?

It took a year from that first awful night for Uncle Yegor to come into my bedroom. Perhaps I should be grateful for that.

My mother went through the motions of stopping him. She tugged on his arm. She moaned. She asked him to come back to her room. But her words were hollow. Formalities. She knew she couldn’t stop him. Her name is Fan, which means orchid. Orchids are delicate flowers. Any sudden change in weather will cause their petals to drop. It doesn’t take much to wither their stems. What she told Yegor the year before about her being strong, capable of surviving on her own, wasn’t true. She wasn’t like a dragon. Or thunder. Or fire metal. She was an orchid, plain and simple, and he knew it.

Although my mother wasn’t putting up much of a fight in my defense, Yegor still wrapped his thick hands around her neck and squeezed until her eyes bulged. He wanted both of us to know he was capable of killing us. We only lived because he let us. He was the god of our universe.

Or maybe he wanted my mother and I to understand, if one of us left, if one us so much as said a word against him, he could kill the other. That was his leverage.

My mother sputtered. Her fingers clawed at his unrelenting noose.

“Stop! Do whatever you want to me. Just stop,” I cried.

And he did what he wanted. He was going to, anyway. He alternated between my mother and me for the next two years.

One day, when my mother was sick with the stomach flu and Yegor wanted beef stroganoff for dinner, I brought home the wrong cut of meat. He walked me down to the corner grocery store to show me exactly how stupid I’d been.

That’s where I first met Sister Loretta. She stole glances at Uncle Yegor and me, and I don’t know how she understood so implicitly, but when our eyes met, she recognized something in me. I felt it. She saw me in a way nobody else had—not my neighbors, not my teachers, not Yegor’s sister, Aunt Antonina. Or perhaps those people did see that thing in me, that broken thing, but they chose to look away because it was easier, safer. Sister Loretta didn’t look away. And neither did I. I saw something in her too.

As we approached the counter with a package of cubed round steak and a bottle of Yegor’s Moskovskaya, she appeared with a cart full of bagged groceries, a savior in an oversized sweatshirt. “Excuse me,” she said sweetly to Yegor. “I couldn’t get my shopping cart over that step in front of the door, so I left it out on the sidewalk, and now I need to transfer over all of these heavy bags. You’re big and strong. Would you help a feeble old woman?”

As soon as Yegor was out the door, she grabbed my wrist and her voice dropped into a lower, gruffer register. “35 Chauncey Street.”

“What?” I pulled my arm back.

“35 Chauncey Street. Mercy House. We can help you.”

Uncle Yegor had half of the bags in the outside cart now. Later that night he would describe his act of heroism to my mother as she shivered with fever. Because despite everything, sometimes it seemed he wanted her approval. Even beasts long to be loved. “Help me with what?”

She meant business and didn’t have much time. She leveled her stare. “You don’t deserve any of this. You need to get yourself out of this situation as soon as possible. 35 Chauncey Street. It’s the one with the angel doorknocker. Arrive any time. Day or night. We’ll keep you safe.” Then she turned to the Middle Eastern man behind the counter and nodded. “Sorry about the switch, Abdul. I’ll bring your cart back tomorrow.”

~

The next morning, before Uncle Yegor woke, I told my mother what the old woman had said, and that I wanted us to leave. She didn’t look up from where she diced cooked beets for vinegret. (She didn’t make anything but Russian meals anymore. Not Chinese, and never her hybrid.) “I have no work, no friends, no family. How do I survive? Where I go? Back to China?” Red juice pooled on the cutting board like fresh blood.

I asked her four more times. Let’s go to Mercy House. At least listen to what they have to say. But her answer was always the same. She feared Yegor, but she feared life without a man even more. And I couldn’t imagine leaving her alone with him. If I stayed, at least we had each other.

I resigned myself to this fate until the day Yegor didn’t like the tone I used to tell him dinner was ready and he put a knife to my throat. The steel was cool and sharp against my skin and his breath was warm and sour. His eyes were crazed, and his pupils dilated the way they did when he thrust himself into me. He was getting pleasure from this moment. It pleased him to have his way with my body, to have his way with my life.

That’s when I decided I would be more than just beautiful. I would be like the dragon.

I told my mother, when I left for school the next day, I wouldn’t be returning. And I wanted her to come with me, to meet me at Mercy House at 3pm, when Yegor had his shift with the taxi.

I waited on the front steps of 35 Chauncey Street for two hours before I gave up on her and lifted their angel doorknocker. Worry for my mother filled my stomach, my head, my mouth. There wasn’t room for anything else. I was afraid that if I parted my lips, my mother would spill out.

So I kept her in. I kept myself quiet. Because no matter how badly I wanted to be like the dragon, it couldn’t happen all at once.

Sister Loretta answered the door. “I’m glad you decided to come,” she said. And then she opened it wider. “Welcome home.”

Alena Dillon is the author of the humor collection I Thought We Agreed to Pee in the Ocean. Her work has appeared in publications including The Rumpus, Slice Magazine, The Doctor TJ Eckleburg Review, and Bustle. She teaches creative writing at St. Joseph’s College and Endicott College and lives in MA with her husband and their dog. “Mei Lei” is an excerpt from Mercy House, a manuscript she’s currently shopping to agents about a gritty nun who goes against church doctrine to advocate for survivors of sexual assault. Visit her at alenadillon.com.