“Till the Clouds Clear,” Image by Dawn Surratt

The rimed windows provide a rounded geometry, the panes rimmed in ice-fern. We move chairs away from them, closer to a room’s interiors. We learn to love audiobooks, short stories on the radio—local readers from Des Moines, and Selected Shorts from Symphony Space. We grow to admire Isaiah Sheffer, our winter guide, who takes us away from the chill rooms and into the world of stories. We develop passions for Mouse Trap, Monopoly, Gin Rummy, Hearts, and Battle. We love baking. The oven is lit and live for hours, it radiates. My kids spend lots of time at the kitchen table to be near the stove, cutting out hearts or winter scenes for shadowboxes, working math problems and English grammar. We love three-season porches, especially on the north side of the house, and the west—the worst cold comes from the northwest, down from the Arctic and across Montana and South Dakota. The porches insulate.

Outside, frostbite is never far off, a ghost that scares us to run ahead. Yet I know of no cleaner smell than the keen, cutting cold. Exsanguination—a few days ago, a friend gave me the word for it. I‘d been searching for ways to describe the air on cold days and the experience of inhaling it. Exsanguination—the blood retreats from the vulnerable parts of the body, most noticeably the nose. This retreat allows the experience of a fierce beauty hard to replicate—when I breathe in the air, it fairly rings through my body. I imagine chandeliers, glasses clinking. On subzero days, the air carries more oxygen. It’s denser, and sustains a freshness I can only describe by what’s absent—the smell of hot tires on pavement, pungent animal odors, sweet organic matter. The short periods I venture outdoors in frigid weather, I hold my breath momentarily, then let the air spiral in, the frosty burn of midwinter in the lungs. Too much time in subzero temperatures complicates breathing–I know this—it causes the airways to constrict. My son has asthma, and he has to be careful in very cold weather. He always carries an inhaler in his pocket. We keep a nebulizer at home, a machine to help him recover from asthma attacks.

~

He waves at us from a screened porch, a familiar-looking man I barely know, a tall, thin man. His wire-rimmed glasses are round, gold moons. He has fair hair, maybe it’s white. My mother stands by him, a wraith in a white mask and hat and gown. Even her shoes are covered. She stands in place, sandwiched between him and an Adirondack chair. There are other men on the porch, sitting in a dozen Adirondack chairs. My brothers and I, our dad, my Grandpa and Grandma Spears, wave back. I look at my Granddad Thompson with a smile, half-expecting that we might have a real conversation. I imagine what it would be like to hug him, to have his arms encircle me. Instead, the scene is surreal, a tableaux, the porch is high up and faraway like a stage. I crane my neck until it hurts. My brothers and I are too young to really understand. I must be five, my older brother six, my younger brother, four—too young to comprehend that Granddad Thompson, my mother’s father, is in the final stages of tuberculosis, which will take him within the year.

I hardly know him, don’t remember ever seeing him before this, and I don’t know where we are exactly. Possibly the VA hospital in Temple, Texas. He’s a World War veteran, so the VA seems the most likely place, and Grandpa and Grandma Spears live in Belton, a small town nearby. Years later an old postcard image of the hospital and its white porches seems familiar to me. Is that where he once waved at us? I wish I knew. This is my one living memory of Granddad Thompson.

~

Some years ago, my daughter Claire brought home from school a paper with creatures on it in black outline. Round creatures with thin arms and legs. She’d colored the forms in primary colors and green.

–Tell me about these, I said.

–They’re snot-boys, she replied, wide-eyed, smiling, triumphal.

–Snot-boys?

–Yeah. You gotta wash your hands or you’ll get a cold.

–Oh, germs!

–Yeah, germs!

The protocols derived from germ theory are pragmatic, they work: wash your hands, cover your cough or sneeze, and wash your hands again, disinfect surfaces, air out rooms, don’t drink after others, repeat the hand-washing once more. The year many of us prepared for the swine flu pandemic I taught in a large, urban high school in the Houston Independent School District. The administration held more than one meeting for the faculty about the expected outbreaks, and officials put into effect some simple measures. Remind students to wash their hands, to sneeze into the crook of an arm, to stay home if they were ill. Then we teachers were handed over-sized bottles of hand sanitizer and a box or two of Kleenex to keep on our desks at school. Of course, I hardly touched the bottle after it had been out on my desk a day or two, because all the students had been touching the bottle. And inevitably, a dozen or so became ill with the swine flu. By luck, I didn’t catch it.

I am still teaching, and I’m not often ill. My own protocol—don’t put fingers in mouth, eyes, nose, ears, unless they are clean. Don’t touch students’ desk, except with a paper towel and sanitizer. Don’t touch anything that belongs to a student, in fact—except that I must handle their papers, at least, so I always wash my hands after a session of grading papers. I keep on hand vitamin C lozenges or Emergen-C or both, along with Echinacea capsules. Okay, does this sound a little obsessive? Maybe, but I’ve been following this regimen so long, I hardly think about it very much. Only in writing down these details, do I realize how careful I have been.

~

My mother, narrator of Thompson family stories, says that my Granddad Thompson came to live at our house when I was an infant, about six months old, and my brother Craig, two years old. Here is how the story goes, according to what I was told, and I have filled in a few details from my imagination:

My grandfather sleeps in my room, a pale blue room with organdy curtains and oak floors. On warm days, the window is opened to let in the breezes. Besides the Jenny Lind crib, there’s a roll-away bed against one wall. My mother’s been using this bed in the middle of the night to nurse me. Now, this is Granddad’s bed. If my mother is still nursing me, she will do it elsewhere.

I do not know how long he lives in my room, but because my mother uses the word lives, I have to assume he stays a while. Why do my parents invite him to stay? They are soft-hearted; they never shirk obligations; they honor their parents. Maybe he’s homeless. In photos, he looks frail. Maybe he’s in poor health because he is an alcoholic. Alcoholics, with their compromised immune systems, are at high-risk for contracting TB. Granddad looks kindly, benign, but when he comes to live with us, he is deadly. He has active TB, though my parents do not know that right away. At some level, maybe he knows he is ill, but he doesn’t know what the illness is, or the consequences.

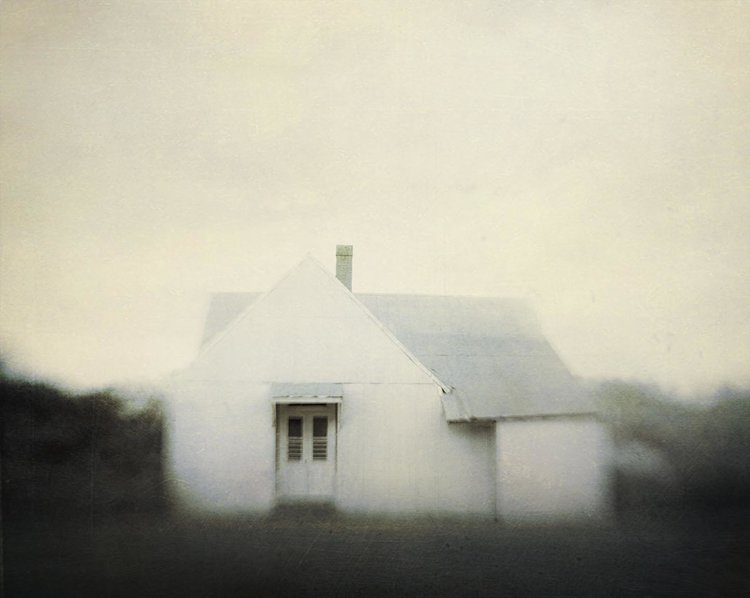

In Waco, Texas, where we lived during that interval, a large VA hospital complex sprawls over many acres. Maybe at first my grandfather received treatment there. Built on five hundred acres in 1932, the campus contains twenty-five red brick buildings built in the Italian Renaissance style, with white stone trim and red-tiled roofs, to contain so much illness and suffering. Though its surrounding acreage has shrunk, the campus still remains an impressive sight by air, and even from Interstate 35 that bisects the town. Up close, I imagine the hospital complex looks bolder. Looking at old hospital postcards provides a window into the world I grew up in, in the 1960s and 1970s, where a lot of pre-World War II buildings dominated towns: Many gorgeous old structures, built on a human scale. Gabled schools with wide porches on the main level, and two or three storeys high. Wide staircases inside and out. Craftsmen houses with ample, shaded porches, wraparound porches, porches that served as exterior rooms, an extension of the houses themselves, porches for dining, relaxing, welcoming, saying good-bye.

~

An early, effective treatment for many TB patients involved rest in a warm climate and plenty of fresh air, along with not-so-quaint procedures, such as “pneumothorax technique” (collapsing a lung to let it rest and let the lesions heal) and “phrenic nerve paralysis” (to ease the diaphragm from a hacking cough probably. But disabling the diaphragm would also make breathing more difficult, no?) Often TB patients were housed in solaria, to capture light and warmth; the many windows could be opened to let in fresh air. Or the patients could be found on wide and sometimes multilevel porches, resting in beds or in “deck chairs,” like the Adirondack chairs I recall on the porch where I last saw my grandfather. This practice gave the patient exposure to the healing sun and clean, dry air. Actually, this was the only known early cure for tuberculosis, before the development of surgical techniques and before streptomycin and capreomycin.

Children with positive TB skin tests most often get the infection from an adult, whose coughs and sneezes contain much more of the mycobacterium tuberculosis, or Koch’s bacillus, than a child’s. Normally, most children exposed to someone with active tuberculosis are tested for the disease, with a tuberculin skin test. If the test results in a raised bump at the site of the injection, the child has been infected with TB, though the disease may lie dormant for a time. But any child under five years old will undergo a chest x-ray, even with a negative skin test. Very young children have a lower immunity than older children and adults. They must be checked over several months for signs of latent infection.

I’ve never had a positive skin test, nor did my brother. I have to guess that Craig and I were never in Granddad’s path when he sneezed or coughed. Did we ever take a course of antibiotics as a precaution? I don’t know that either, but I have a screaming recall of chest x-rays and being held down tightly. Even now, whenever I have to have to TB skin test for job purposes, I feel a tightness in my chest for days, waiting to hear the results of the test.

~

When I was a teenager, I took to lifeguarding in the summers. I loved to swim. I used to swim so much that my dreams often involved swimming underwater for extended lengths of time—and holding my breath. Often I’d wake myself up, out of breath. The last moment of dreaming, I propelled myself up to the surface, my heart beating audibly, gulping the good air. A mostly clear, rippling surface of water served as the matrix for my summer waking hours. I watched people swim. I swam. At night, some of us lifeguards would meet up, to climb over the fence of the public swimming pool and take a surreptitious swim. Swim some more. We couldn’t get enough of it. I became an expert at forward motion just below the surface. I could hold my breath for well over two minutes, if not longer. Sometimes I wished that I could just breathe in the water and take the oxygen from it, instead of rising to the surface to take in the air.

~

Christopher Koehler, in “Consumption, the Great Killer,” speaks of the romantic portrayals of TB in nineteenth-century literature and music, especially in the characters Mimi of La Boheme and Satine in Moulin Rouge. Their deaths are meant to depict something tragic, and beautiful. Yet, Koehler tells us, “the dying consumptive faced night sweats and chills, paroxysmal cough, spread of the disease to other organs of the body, and of course, the wasting away that led helpless bystanders to name the disease ‘consumption.’ ” Of course, these characters were also exposing others to their deadly disease. Before the advent of antibiotics, about eighty percent of TB sufferers succumbed to the illness. Twenty percent survived, however “romantically” or frightfully they recovered, to breathe new air into their scarred lungs, good air that traveled in blood cells through their wasted bodies.

Even though my grandfather lived in the era of antibiotics, he was not ultimately saved from tuberculosis. His lungs were weakened from smoking, his immune system compromised from alcoholism. Granddad was born into a wealthy family that became destitute in the Great Depression. My grandmother divorced him early because of his drinking. He’d fought in a world war. He’d seen a lot of hardship before he died in his sixties. And he died a hard death. As a child, my last memory of him on a porch, smiling and giving us a wave, was confusing. I wasn’t told that he was dying, that this would probably be the last time I would see him. The moment did not seem tragic then, just curious. Now I see him in my memory, half in sun, half in shade, with his semi-smile and weak wave, about to turn around and walk fully into the arms of his disease.

~

This past summer I had a small cabin built on some wooded land. The cabin is painted a soft green to blend in with the surroundings. There are sitting porches built onto the front and back of the cabin. I love porches, the fresh air, the wind through the trees. The wind in the trees imitates the sound of taking air into our bodies. Porches connect me to some of my strongest memories. Not only do I see Granddad Thompson waving from the hospital porch, I see my cousins and myself roughhousing on the big wraparound porch at Grandpa and Grandma Spears’s house. In Colorado, my brothers and their families relax on the front porch of our cabin some summer mornings until 11 am or noon, reading, talking, watching the hummingbirds, planning a hike. At my childhood home, there I am, a teenager, with my friends sitting on the front porch late at night, just shooting the breeze, laughing. And while we laugh, we fill our lungs with deep draughts of cool night air.

Rebecca Spears is a writer and instructor from Houston, Texas, author of The Bright Obvious (Finishing Line Press). Her work is included in TriQuarterly, Calyx, Crazyhorse, Verse Daily, Image, Relief, Ars Medica, Nimrod, Borderlands, and other journals and anthologies. Currently, she writes online posts for Relief Journal and serves on the board of Mutabilis Press. Spears has received awards from the Taos Writers Workshop, Vermont Studio Center, and The Writers Colony at Dairy Hollow.

Read an interview with Rebecca here.