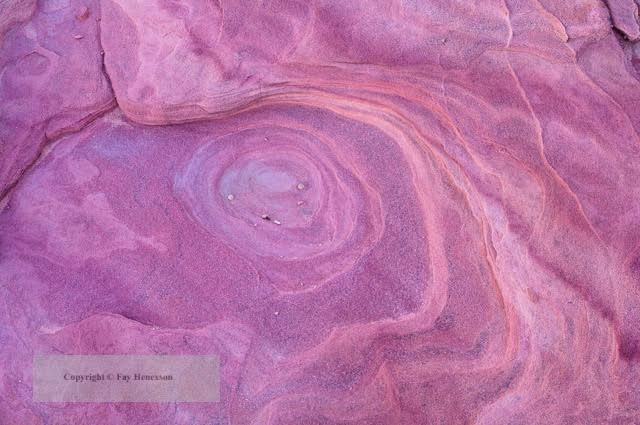

“Triptych of Textures,” Photograph by Fay Henexson

On Perseverance

12 step groups say: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again expecting different results.” No it’s not, I say, irritating the hardliners. The definition of insanity is not being able to distinguish between reality and non-reality. In psychiatric terms, people who do repetitive actions are perseverated. Perseverated means stuck. You wash your hands twenty times, three, four, five, six or more times a day, or check to see if the stove has been turned off dozens of times before you leave the house, or, like me, you never veer from taking the Manorville exit because you’re terrified to get lost.

I’m not insane. I have General Anxiety Disorder, which is a kind of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that can manifest in panic attacks so wild you appear momentarily schizoid. But I soldier on regardless. “Follow your fear.” My greatest fear is of success, not failure. I do failure well.

Perseverance is another way to define “doing the same thing over and over again expecting different results.” Go to enough meetings, you may never like them but you’ll learn about humility in action. Hemingway wrote the last page of Farewell to Arms, thirty-nine times to “get the words right.” Brenda Miller works on her essays for twenty years. I began the first draft of a memoir in 2000 the year after my mother’s death—I’m still writing it.

I recognize my own perseveration – it’s emotional – The beauty is I persevere anyway.

On Failure

Drawing, acting, being a daughter, mother, wife, and writing: I failed all of it until I got sober. Not that I was drunk from day one–albeit family lore has it that my mother put diluted gin and tonic in my baby bottle to offset diaper rash. Alcohol at my house spelled anesthesia. Weary of alcohol induced amnesia, I put it down and examined my ills. The crux began with lively and bright bifurcated parents; my mother from my father; her mother from the past; my father’s mother from four marriages; and my father from madness. They failed. Themselves, each other, and the children they produced.

“It doesn’t matter how rotten you are, or if you fail. A failed parent is better than a dead parent. A failed parent at least gives you someone to rail against.”

–Louise Erdrich

I failed to keep my father alive; I couldn’t prevent his becoming a ghost. How I would have loved his failure in the flesh; I would read to him poems by Roethke on the sadness of pencils, passages from Erdrich’s Plague of Doves, and Virginia Woolf’s failed righting of a moth. . ..

I am failing now.

I try again. I am failing better.

On Suicide

My father wrote poems, painted, and acted but none of that saved his life. Of course, he was a paranoid schizophrenic, dead by age thirty-nine – he hanged himself with his belt nailed to a door frame the summer of my fifteenth year. I doubt writing about his mother, who had him as a teen, could have made him well. I don’t like writing about my father. He was an absent father and his last action wasn’t a gift. I went to his funeral alone where I met his mother for the first time in my recorded memory. After his death I turned him into a potent specter I sought in the beds of strangers.

Having failed to take my own life a couple of times, I am an unsuccessful suicide. I have written about my mother and grandmother and me, but writing about my father feels insurmountable, and not just because I didn’t know him.

Maybe I like that omnipotent ghost too much.

Maybe putting him down on paper will transmogrify my flesh.

Maybe I’m a masochist who won’t let go.

On Funny

“Bundled in the back seat of a United Taxi cab, Mama and I set off on yet another one of our adventures: I to have an abortion and Mama, lunch—she’d brown-bagged a sandwich to take along.” That opening made me laugh. From laughter I could write my abortion story. My mother packed a sandwich to eat in the waiting room of the clinic, a few feet away from where her only child, a twenty-two-year-old college girl has the inside of her uterus suctioned out. There was never a question of keeping the baby. “I’m not going to be a nursemaid for anyone or anything unless it’s a ticket out of here,” Mama said when I’d broached the idea.

Mama called herself the head psychiatric and geriatric nurse at The Crisis Center, her term for our house. Mama was the “Boatswain of Crisis” and I was the storm. Dear God, but Mama was funny. Funny saved my life time and time again. Funny allows me to step away from what’s sad. There was such sadness at home anesthetized by alcohol and books. The booze did so much damage but the books saved us from truth—

Living with each other required fiction on all our parts.

On Mothers and Daughters

Mama was a looker: brilliant brown eyes, a Patrician nose and coral mouth, shoulder-length red hair, small waist on a five foot seven frame, Double D breasts, and a dancer’s calves pixilated by thousands of pale red freckles. But it was her wicked wit, powers of observation, and literate mind that brought me to my knees. Mama got her looks from Ellen Virginia Tobin White, the maternal family matriarch known as “Mummy.”

“There’s little Mr. So-and-so standing in the corner looking like a pale cocktail onion,” Mummy’s purported having said.

I have a picture of my grandmother and Mummy taken in Biloxi, Mississippi, 1935. They stand on a front porch, looking like weird Siamese twins bound at the hip, hair in identical bobs, and wearing Mary Jane pumps. Mummy coyly tilts her neck and eyes the camera. My grandmother squints; looks away.

“You’ll survive because you’re the center of your own universe,” Mama once said to me.

I look like Mummy and inherited the matrilineal tongue—when it comes to my own daughter, I bite it.

Lucinda Kempe’s work has been published or is forthcoming in Jellyfish Review, Summerset Review, Matter Press’s Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, decomP, and Corium. She won the Joseph Kelly Prize for Creative Writing in 2015 and is an M.F.A. candidate in writing and creative literature at Stony Brook University.

Read an interview with Lucinda here.