Diane Buccheri: A statement up front before we start: Tom, you keep alive everything that passes in front of, around, and in you, like flowers that never die. You pick each flower and write a story or a poem, recovering the details barely imaginable in daily life. I know you grew up with your paternal grandmother and maternal grandfather feeding your literary hungers and tastes, fighting for your palate. How do you tell younger writers to depend on such memories rather than ditching them like today’s plastic wrapping. Because you write in many voices, genres, do you know or recognize what makes a new day a poetry day or a prose day for you? Are there tell-tale signs saying where your energy is going, in what direction, for what cause?

Tom Sheehan: When I go down inside myself, searching or alerted to some knowledge, possession, kinship with an idea, a moment, it’s all of me being searched and telling me where I’m going, what I want to say. There are times when certain words leap to be said again, knock themselves loose from tissue holding them in place, to be used, to come out of their cover for a further idea, a metaphor, a stick to measure by. Such words are not created by me, but are borrowed for this occasion, this particular use … they’ve been around for a long time on their own, waiting to be picked up again by passersby, like me, like others before me. When a poem comes out of it, it’s hot light, lightning, illumination on the leap.

Prose takes another road and is often catch-as-catch can, simple as looking out the window from my chair where I can see the river (high tide, low tide, mid tide), the road, the wide cast of birds in the skies (pigeons, ducks and geese, cardinals, hawks, turkey vultures, yesterday an enormous black-winged eagle supposedly mastering his sky and being chased by a hawk a fifth of his size), the traffic, a chunk of history from the First Iron Works in America where I worked on the reconstruction 64-68 years ago, a site once operational from 1632-1638, and reconstructed and dedicated as a National Park, and my home being built 100 years after the initial operation. I am so travelled back in time, thrust into situations, exposed to characters who had a place in this founding … who hang around for the likes of me all these years later. Objects come at me, those past characters in their plights and situations demanding answers or resolutions, and I am impelled to complete the reconstruction of the whole site. I swear I hear the Scottish slave workers talking about home after their importation for laboring with iron ore, turning the world over on its side, ballooning great industries.

Diane: You get under the skin, into the hearts and minds and senses of each of your “characters” who are indeed real people or become real by your writing. Your sensitivity is astounding, even to me, after reading and publishing your work for over 10 years. How much is taken directly from real life?

Tom: Every word, every poem, every lie, every story, is taken from something, some place, someone I have encountered.

Diane: Do you ever know a piece or poem is done?

Tom: I fear there is always an imperfection that can be found, can be fixed. It’s nice to think that in 50 years, or whatever, someone will read a piece of mine and say, :”What he meant here is…” Perfection is search.

Diane: In your reading, what things stay with you?

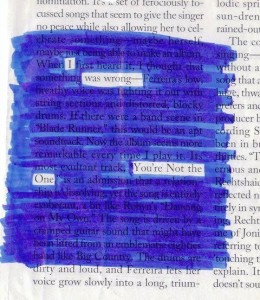

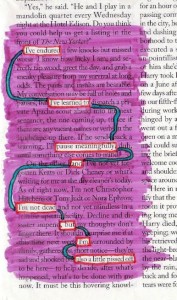

Tom: Where words leaped at me, the explosions of the language, where a highlighter might go crazy on a page: Thomas Wolfe’s “O waste of lost, in the hot mazes, lost, among bright stars on this weary, unbright cinder, lost! Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language, the lost lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door.”; Melville’s “Call me Ishmael”; McMurtry on horseback; a poem I’ve recited a thousand times … John F. Nims’ “Shot Down at Night”; hearing W.B. Yeats’ recording of “Lake Isle of Innisfree“; introducing Seamus Heaney to a standing crowd at St. Ignatius Church, Boston College, part of the James Joyce celebration, March 2, 1982.; a classic lead sports page paragraph of a Boston Globe sports report in October of 1941 by Fred Foye: Harrington-Shipulski, Shipulski-Harrington. Shipularington Harringpulskiton :The names Mike Harrington and Eddie Shipulski became a dizzying maelstrom of air bombs, bucks and touchdowns, and when the nose drops were administered here this drear day undefeated Melrose awoke to find itself defeated with Saugus High School, otherwise known as The Shipulski-Harrington Athletic Club, leaving town with a 13-0 victory.(I was in love with the language and the sport.)

And my father saying, early in the games, at the edge of my first failure, marked by the touch of his hand on my shoulder, You come into life with two gifts, love and energy, and baseball and football and hockey are going to take both of them for all you’ve got. I think his heart remembered a loss, his knees their pain. When they took his leg off, the pain did not leave him.

Diane: How often do you participate in readings?

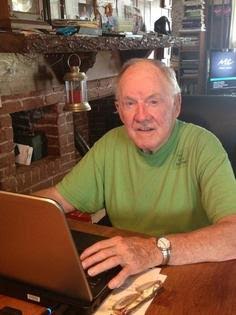

Tom: At 88, only the regular venues over the years; Out Loud Open Mike at Beebe Estates in Melrose (for 15 years perhaps) with Melissa Wattenberg and Rick Amonte, and the Jellicle Literary Guild in Melrose, MA with Raymond Soulard, editor of The Cenacle.

Diane: Do you remember your first reading, the last?

Tom: The two go together, strange as it seems: On Wednesday night, April 27, 2016, I had a revelation as I sat in the audience, waiting for my turn in a reading at Out-Loud Open Mike at the Beebe Estates in Melrose. Out of nowhere I suddenly remembered my first public reading 80 years earlier in Marleah Graves’ 2nd grade classroom of the Cliftondale School in Saugus, MA. I have lived here in Saugus since 1936, 80 years of my lifetime. We second graders sat on little green chairs in a circle in front of the classroom and I had written a piece on two pages of math paper about the freight train logos that passed daily through a local train crossing, or came out of my rabid reading about “elsewhere,” such as The Route of the Phoebe Snow, The Lackawanna Valley, The Boston & Maine, The Nickel Plate Road, The Hiawatha Line, Aroostook Valley, Bangor & Aroostook, Chesapeake & Ohio, etc. The names, the geography of them, fascinated me and my quest for learning more. When I finished my piece the girl beside me jumped up and kissed me on the cheek. Shortly after my son Jamie was born, about 40 years later, my wife Beth and I went to a plush restaurant where we first had to stand in line and wait for seating, and when my eyes met the eyes of the hostess, she said, loudly, “The Sheehan party, please.” And it was the same girl who kissed my cheek on that long-ago day, and we were seated right away. (Note: the school building is now named in honor of the teacher, the MEG Building, and serves as a civic center.)

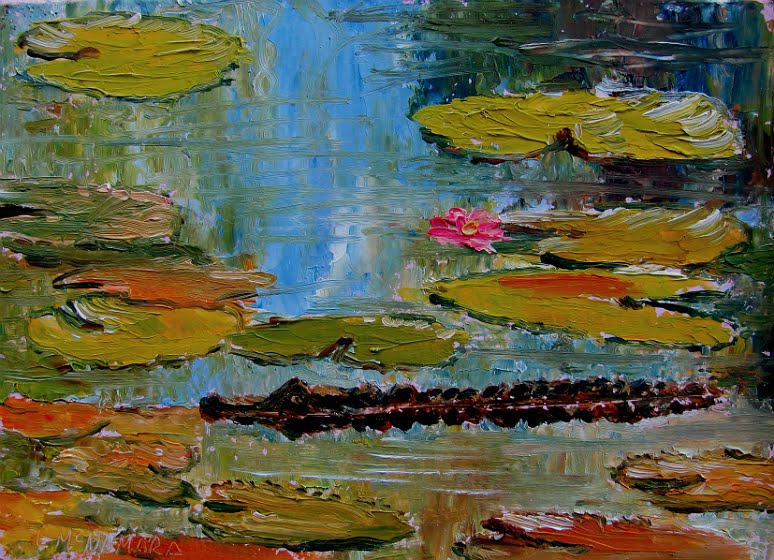

Diane Buccheri is the founder and publisher of the former OCEAN Magazine. OCEAN led her into photography. Words and images fill her days. www.dianebuccheri.zenfolio.com