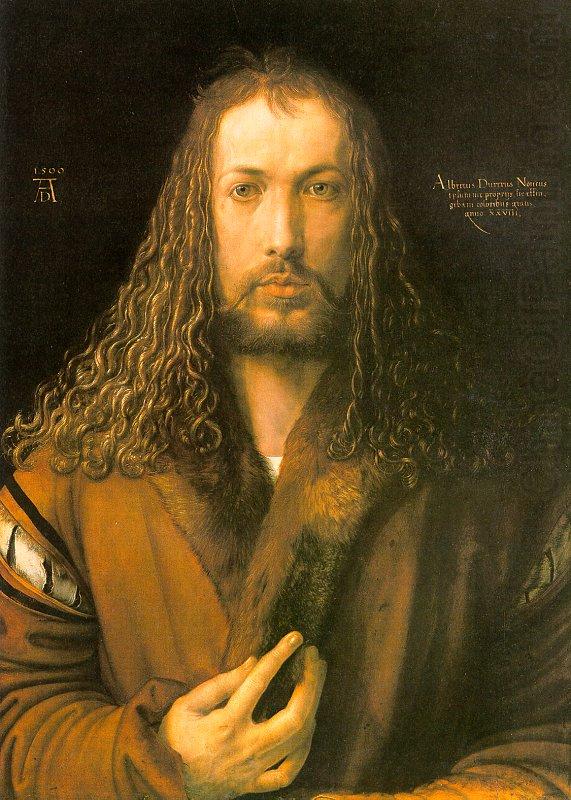

Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight Years Old Wearing a Coat with Fur Collar by Albrecht Durer circa 1500

I bought my brother Davey a winter coat when he was sober, finishing his long interrupted college degree, and staying on his anti-psychotic medications. David, I mean. He’s forty-five, not a kid any longer. He stayed sober and sane for the past six years. Something changed. A hormone shifted. One of his pills worked too little. Or it worked too much. Some hand of fate loosened its grip, or, grabbed tight, and he was drinking again, calling at 3 a.m., telling me what the feral cats were telling him, fighting with his psychiatrist, fighting with our mother, filling his credit cards with purchases and returns and re-purchases and re-returns of iPads, laptops, and the Oxford English Dictionary, twenty volumes, delivered who knows where. He gave away or threw away or somehow lost his winter coat.

After a stay at detox and then a psychiatric hospital, Davey is living with our mother and reading the copy of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations that he asked me to get him for Christmas. Written nearly two thousand years ago, Meditations is the thoughts of a Roman Emperor on accepting duty, service and other things, like fate, that I don’t worry about given that I’m busy in the world of law, intellectual property, and money. Davey’s resigned to circumstances; I make my own life.

“Bad job on the translation,” he says over cheese omelets our mother cooked. He wears a white wool sweater and jeans that are Christmas presents from our mother—from me, since I gave mom the money. Davey’s voice sounds as if he borrowed it from a stranger. He looks unfamiliar; but it’s been three years since I’ve seen him, and I’m tired from the cross-country flight. Davey and I still have the red hair and freckles of my mother’s side of the family. We’re both thin, but at 5’7” I’m taller. He still has that scar from when he was beaten up and too drunk to fight back, but his meds are user-friendly these days, no dead-eyed staring and jerky motions as from the Stelazine and Thorazine. We have my father’s blue eyes, but David’s are sad, as if he’d fallen down a rabbit hole and emerged when he was thirty-nine, not knowing what his life was or where it had been. We had such hopes during these past six years when he finished his B. A. in classical literature and applied for graduate school in education. Hope rose like ghosts from our childhood’s grave.

Optimism comes from my father’s side of the family. So does schizophrenia. Although mom thinks Davey’s bipolar, too.

“All right, I appreciate the gift, it’s just very modern…” Davey says, tapping his index finger on the table.

“That’s bad?” I ask. “Making an obscure book accessible? Maybe you would have preferred it in Latin?”

“Can you go shopping with David for a coat?” Mom intervenes, frowning. Her once crimson hair has faded to cinnamon and grey. Her brown eyes are tired. She butters the orange-currant scones she baked for breakfast. Some patent work on a web-based media, and I had the cash to buy her this two-bedroom condo with its kitchen overlooking the marina. My money can’t resurrect her dream of starting her own restaurant; that died with decades of Davey’s arrests, hospitalizations, medication changes, disappearances, and returns to her doorstep.

Now it’s the morning after Christmas. January promises snow. Davey needs a winter coat to replace the one he lost.

“Sure, I can drive him to the Mall.”

“Can you go shopping with him?” Mom taps her finger on the table as if she and Davey are sharing a bongo drum.

I know what she won’t say while he’s here: you’re his sister; sooner or later, he’ll be your responsibility.

~

Davey holds the North Valley Mall doors open for a white-haired grandmother hauled by yowling kids.

“After you,” he says and heads for the Mountain Sports’ Menswear section.

He scans the racks of North Face parkas, Columbia rain gear, Coleman all-weather coats, assorted down jackets. He rubs hood ruffs. He tugs at zippers. His hands drop. His nose wrinkles. Wrong color. Seams aren’t tight. Down isn’t waterproof. Too short. Too long. A raincoat, not a winter coat. A parka, not a snorkel coat.

“Just what kind of coat are we looking for?”

“I’ll know it when I see it.”

We cross the mall to Burton’s Fine Clothes.

“Not here,” he says after a jet-fast scan of the coat racks.

We walk past screaming children and arguing spouses to reach Macy’s.

“No,” says Davey. Half-off signs hang over Women, Petites, Children, and Shoes. Menswear is a full-price wasteland.

“Trust me. Cost is not a worry. Get a coat and if you don’t like it, we can get you another coat.”

I don’t tell Davey of the client who called me at 9:30 a.m. on December 23rd desperate for a three-hour job for some minor software package that couldn’t wait until the 27th. It was four hours before my flight. “That will be $5,000,“ I had said, folding silk shirts and black jeans into my suitcase. He screamed; he cursed; he paid. I went online in the departure terminal, finished the job as the plane cruised over the Rockies, and emailed it to my client during the layover.

Davey scans the racks but stops to pull out a neon orange coat.

“Wrong color,” he mutters. He shoves his hand into the pockets. He checks the lining. He rolls his eyes at the price tag.

A sales clerk rushes over and says, “Happy holidays, how can I be of service?”

“Hello. How are you?” asks David. His words are a second late as if he’s translating from a private language; he waits for a reply. The clerk blinks and looks to me.

“I need this in a different color…” I start to say.

“Alright Joan, thank you, but…” Davey cuts in.

“Our post-holiday stock is on display,” the clerk explains, “We could order it for you.”

Davey puts the coat on the rack. I pull it off.

“Joan, alright, wait a minute!” My brother protests.

“I’m handling this Davey…”

“Call me David…”

The clerk blinks. Out of the corner of my eye I see Davey tapping his finger on the coat rack.

“Can you do a rush order? And do you have tailoring?” I continue.

Davey grabs the coat, shoves it onto the rack, pushes other coats around it, and turns to the clerk, saying, “Thank you for your help, have a nice day.”

The clerk blinks and walks off.

“Davey, we could have finished this…”

“It’s David…”

“Whatever…”

“No, it’s David. That’s my name… not that kid’s name, like I wasn’t…just say David, all right?”

“The coat is what’s important! What were you thinking?”

“C’mon, that guy would’ve wanted shipping, tailoring fees, extra charges for special orders…”

I almost say: that’s how normal people buy coats. Instead, I count to ten. I never believed Mom’s stories of giving Davey $10 for yard sales and having him come home with a Bill Blass robe and The Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson. Mom said he once found a leather-bound edition of all of Shakespeare’s plays and talked the owner down to $4.50 and The Hunt for Red October thrown in for good measure. (“He knows I love the thrillers,” Mom said.) Mom said that after Davey’s last binge —after he had been missing from the halfway house; after his photograph had been sent to emergency rooms, morgues and police stations; after he was found by the river — he was vomiting blood and booze onto an Armani jacket, a Goodwill tag stapled to the sleeve, a copy of Gilgamesh in his pocket.

“I’ll cover that.”

“But where’s the deal?”

“David, how many stores do we have to go to? There are other things I could be doing. There are even other things you could be doing. And there’s no better deal than a free coat. So let’s just get a coat, okay?”

Davey stares, as if he’s going to say something, but walks off. Maybe he counts to ten, too. We return to our car. We drive to the Woodland Mall. We are silent. We park, pass a labyrinth of cars to reach the elevator, and go to Mervyn’s on the 4th floor, Target on the 3rd floor, T.J. Maxx on the main floor, and the Men’s Warehouse in the annex. We find trench coats, Jefferson coats, snorkel coats, and leather coats. We find parkas and intricate poly-pro layering systems that fit under all-weather shells. We find coats that are tan or black, not navy blue, or that have fake fur ruffs not real rabbit fur, or that don’t reach past the hips, or that reach the knees, or that have no drawstring to cinch the waist.

We drive to the Central Valley Mall, Davey staring out the window, his nicotine-stained fingers on Meditations. We have a fight at REI.

“Did you take your meds this morning?”

“All right, what are you, my caseworker?”

“It’s been eight stores, Davey, maybe that’s who you should have gone shopping with…”

“All right, I appreciate the help, your driving and all, but call me David!”

“Well, thank God for my help,” I yell. Shoppers stare. I lower my voice. “We’ve only been driving all day…”

“All right, we need boundaries, this is my coat not yours, ” my brother declares.

“Do you always sound like you’re in therapy?”

He winces. I wince. Of course he always sounds like he’s in therapy. That’s where he is when he’s sober. Therapy. AA. College classes. That’s his life.

~

“Do you need me at Bargain Coats & More?”

“No. Why don’t you get some coffee?”

When all is lost, you can always find a Starbucks, and we do.

“It’s on me,” he says.

“I can get it.”

“Yeah, you told me, but I have money too. Cuppa joe,” he calls to the barrista.

He rummages through his jeans, pulls out a wad of dollars in a money clip, closes his eyes and says: “He does only what is his to do, and considers constantly what the world has in store for him—doing his best, and trusting that all is for the best. For we carry our fate with us—and it carries us.”

“Davey —David,” I say, holding up my hand. “Your meds, you did take them, right?“

“Relax, it’s from the Meditations. Duty and opportunity. Marcus Aurelius is famous for that.”

“Sounds like a fun guy.”

“He’s expressing the Stoic philosophy. Life is rational, nature acts for the best, and the worst can be endured for the better. You should read it,” my brother says, handing over my coffee. “Just my way of saying, all right, I’m not teaching like I wanted, but I get man-around-the-house, fix-it jobs from mom’s friends.”

After David leaves, I get a double tall Americano. There was no need to embarrass him by correcting his order. Sitting at a tiny table, scanning my Kindle, I can’t remember many times when I was nice to David. It’s hard to think of that now when I remember his courtesy to store clerks and grandmothers. I don’t like remembering how we had read the Wrinkle In Time series together, and the Lord of the Rings, and how David had written to J.R.R. Tolkien for a dictionary to learn the Elf language. I don’t like remembering the summer Saturday nights we’d haul our beaten up kid’s telescope onto the back porch, David telling me the myths of Lyra and Orion and Cassiopeia, me searching for new meteors, new comets, new stars, mom chasing us back indoors right at midnight. I don’t like remembering just before I was sixteen, and David was seventeen. The year it began. When David would laugh and shriek through the night. When, for him, a chair became an oracle, and a can of beef barley soup became filled with worms.

I found my calico cat with her blood soaking into the back yard’s dirt, her skull smashed in, bits of her brain stuck to a red brick. I screamed for my mother.

“An accident,” she said. She was crying. “What else could it be?”

I knew then how it was going to be. I gave away my gerbils. I didn’t ask for permission before finding a new home for Mr. Charles Ames, our schnauzer. Meanwhile, Mom kept a steady stream of psychiatrists, therapists, faith healers, naturopaths, and acupuncturists flowing through our home.

I remember when I first saw David in the hospital.

“He didn’t mean it,” my mother kept saying.

David was sweat-soaked and turned away from the other patients: those without belts in their pants or laces in their shoes. My parents accompanied me, but I was alone—alone with the memories of the police arriving, of the ball-peen hammer David had used to pound demons out of my sleeping mother—didn’t that prove David loved us, and we loved him, he was trying to save my mother from demons—of my father throwing David to the ground, of my mother shaking and crying, of bruises on her arms and blood on her face, of screams. The neighbors said the screams were mine.

At the hospital, I remember David sat staring at a wall.

“Speak, friend, and enter,” I had said saying the words used to open the dwarves’ lair in The Fellowship of the Ring.

“Go away,” David told the wall.

I did. I asked David’s psychiatrists if I’d become like him. Back then, the psychiatrists were Freudians , so they blamed the mother, or Laingians, so they blamed the mother, the father, the sisters, and brothers. Then they said it was genetic, so they blamed the parents’ families. Now they say it’s genetic with an environmental trigger, like drug use or trauma, nothing I could do anything about. So I did what I could. I worked as a library aide after school and a babysitter on weekends. I had dinner at friends’ houses where no one screamed, no one talked about medications, and it was safe to have knives at the table. I studied, earned scholarships, went across the country to college, found summer jobs away from home, and only came back at Christmas. I accompanied my mother as she brought coffee, sandwiches, and books to David when he lived at the halfway house, the treatment center, the hospital. I went to law school and became rich. David came of age and lived on the street.

Now our father is dead. Our mother is old. What will happen when I’m the only one to look after David?

~

David taps me on the shoulder. “No luck at the so-called bargain store.”

I tap my watch. Time’s gone; all I’ve done is remember things I can’t change.

We walk to the car. David hunches in the back seat sending plumes of smoke into the twilight air. David loved holding my gerbils in his now gnarled hands. He loved petting Mr. Charles Ames until the dog licked his nose in a frenzy of gratitude. He loved being my big brother, the one who kept my secrets, the one I trusted.

“Still reading Aurelius?”

“Yeah,” he is quick to respond, “listen to this: Does what’s happened keep you from acting with justice, generosity, self-control, sanity…”

“That’s quite a list,” I laugh.

“… prudence, honesty, humility, straightforwardness, and all the other qualities that allow a person’s nature to fulfill itself?”

“You believe that?”

“On my better days, yeah,” he replies. “At least, I hope so.”

I cannot love David. Perhaps something else is possible. I don’t know what.

“That’s not the way to Mom’s,” David calls out.

“I’m taking an alternate route,” I say. “Humor me.”

~

We see a strip mall where we stop, walk into Martin’s Menswear, and David sees his coat.

“All right. There it is. And in my size.”

I grab the coat off the hanger.

David grabs it back. He stuffs it between two other coats, saying “I saw a 20% off coupon in the Bay Guardian.”

I count to twenty. I imagine ripping the coat to threads. I count to ten. This is all David has. The delusions, the hallucinations, maybe even the drinking are held in a delicate biochemical balance he can’t control. Finding the deal is still his.

“All right,” I sigh. “We’ll do it your way.”

We traverse the mall in search of a Starbucks with a Bay Guardian. We drive to the next strip mall, find a shoppers’ kiosk with a Bay Guardian, drive back to Martins Menswear, get our feet in the door and the coat off the rack and past the cashier with ten minutes to closing. David wears the coat as we walk out of the store.

Stars beam in the blue-purple night. I’ve seen that color in crocus bursting above ground in an offbeat blast of January sunlight. They can’t last. But there they are. Like the hope I had during the past six years of David’s sane, sober life. I want the hope. I want the hope because I want my brother back.

David beams. He stretches his arms. The navy blue coat seems to merge with the darkness. Cuffed sleeves notch over his wrists. A fur hood surrounds his face. The pockets are deep enough for books, a sandwich, a thermos of coffee, a bottle of rum. The coat is a den of warmth for a college student waiting for buses. The coat is a home a homeless man could carry on his back should David return to the streets. Perhaps not for months. Or years. Perhaps never. Perhaps tomorrow.