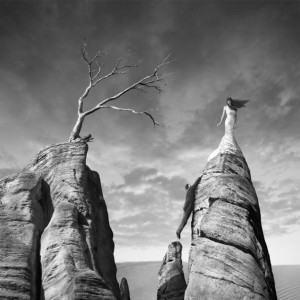

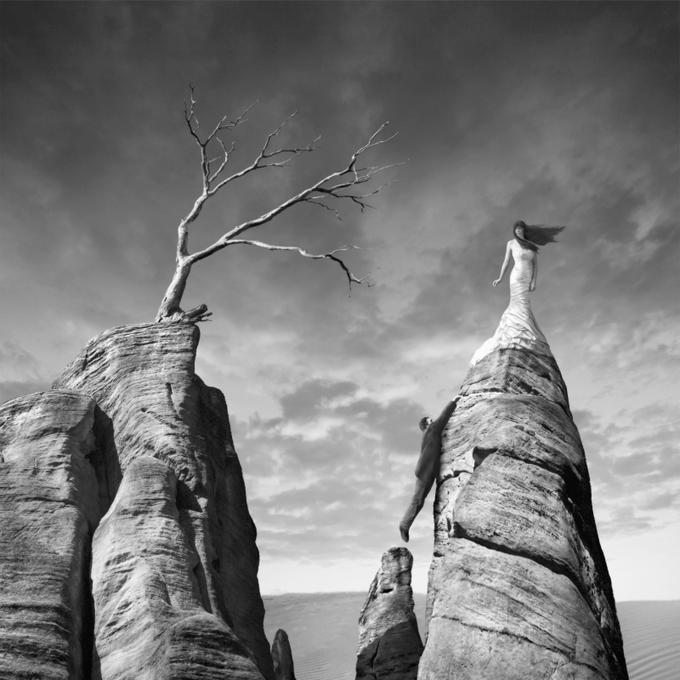

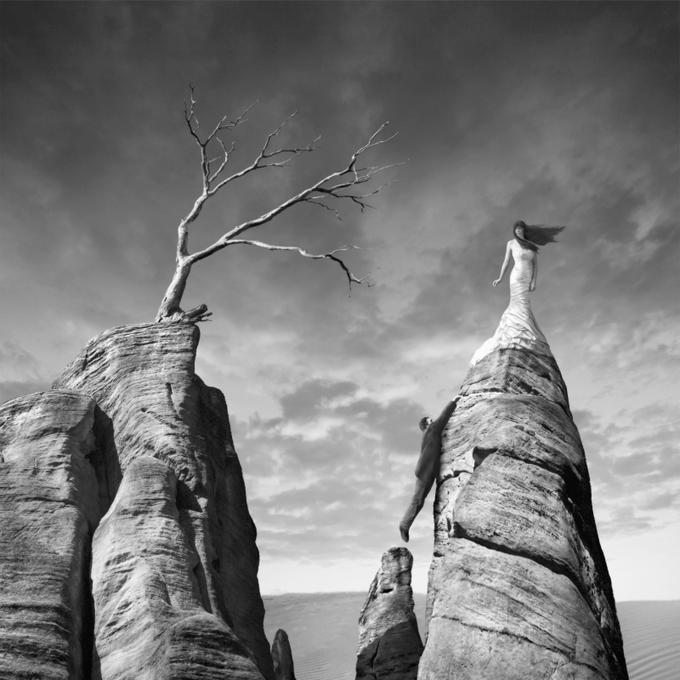

“Peak of Love” Image courtesy of Dariusz Klimczak

I’m laughing in the fall. Laughing the instant control dissolves, the laughter replacing fear somehow, the laughter a vanishing into space, a lightness, a return.

Emma hears my laugh from below. “You were like a kid,” she’d say later, “It was almost a giggle.”

I haven’t made it very far up the rock face before I realize I can’t go back. The ledges are too narrow and spaced too far apart, the sheer walls slick where they’ve been cut away. I was an idiot to start in the first place, but I’d seen guys scramble their way up before, then leap into the still pool below, and something about the quiet contentment of the day made me brave or adventurous, or simply stupid. Now, I cling to the smooth stone, my feet tensing on a narrow shelf, staring into the forty-foot drop below then tilting upward across sixty feet to the rock ledge above where everyone jumps.

Emma is staring off across the still surface of the water in the center of our picnic blanket. Now and then her gaze turns lazily toward me and she waves and smiles.

I shift my feet on the shelf, clutching a jut in the rock with one hand while the other flaps cluelessly in the air. I flatten my body against the stone, then lean out as little as I can to find a path above me, twisting this way and that an inch or so from the wall. The air is calm and silent. I slide my free hand over the face in front of me. It’s warm in the strong sun, polished and bright.

It’s easier once I accept the situation. I give up looking down, trying to determine how to return; I only look up. I don’t think about the ground, I think about the top. I find one handhold then another, inching up an arm’s length at a time, balancing my toes on the thinnest slip of rock, my fingers pushing into small crevices. Now and then, I come across a tiny stand of grass or a seedling tree clinging to a slight layer of collected soil.

I lose my breath twenty feet from the ledge and have to stop, my feet angled flat against the face, one hand over a crag. My knuckles scraped, my fingertips sore, calves trembling. I rest my cheek against the stone and listen to the surge of my pulse, my chest pushing at the rock until it settles.

The sky is a brilliant clear blue above the ledge and just before I crest, it’s the only thing I can see. I pull myself over the lip and onto the plateau. I lie there for a moment, the loose dirt and gravel sticking to my arms and face, then I roll onto my back, staring into the cloudless sky.

Emma is watching for me when I stand. She applauds, I take a bow. She lies back along the picnic blanket. Her dark skin and red swimsuit against the blanket calling to mind a languishing exotic bug.

There are higher ledges in the quarry—it’s impossible to know if anyone has attempted them—but my view is magnificent. The still bowl of the sky and the motionless water. The rose and umber layers of stone exposed in sheer cuts hundreds of feet high.

I brush the grit from my bare knees, drunk on the sense of achievement arcing the surface of my skin, the tips of my tender fingers. It’s a clean, blue burn with no thought and no voice; a particular kind of exhilaration I haven’t felt since I was a kid. A moment of stillness; the active hum sometimes felt after music ends.

The last notes fade and Emma raises on an elbow from our sprawl in front of my stereo. We’d met at a party, some large, swaggering house party. I was in my fourth year, she was in her third and it was a loud night of drinking, dancing, pushing people into the pool. It’s humid and sweaty and we’ve only just met but we start a conversation, shouting over the music and noise, a conversation that halts and spins with shouts from another room or someone lurching between us and collapsing onto the sofa.

And we talk, until we end up at my apartment, sprawled on the floor before the stereo, a few feet apart. And we listen to ‘In the Aeroplane, Over the Sea’, not speaking at all. We’re silent from start to finish because that’s why I’d brought her back and when she raises on her elbow in the stillness after the last note, opening her eyes for the first time since the CD began, her face slick and flushed, I believe I have some glimpse of her secret nature, something definite and mysterious.

The sense of silence changes shape when I reach the edge and look over. My body stutters back from the view, from the possibility of the limitless drop toward the surface, back six feet to the rock wall at the other end of the ledge.

There’s nowhere to go but up. Or into the water. I know the water is deep enough; I’ve seen others dive over and over, tanned bodies folding straight and razor clipped, slicing the surface and disappearing for so long I’d wonder if they were coming up again.

I resist the urge to look back down the rock face in hopes of finding a hidden traverse invisible before. I back away from the lip as if preparing to race forward and into the void but I’m not going to do that. I know I’m not going to do that. Instead, I make my way toward the ledge, gazing across the quarry toward the blank, opposite wall, then down into the motionless blue surface below.

I inch my bare feet over the edge, the crust of the rock scuffing into the soles, my toes curling over air, until only my heels bind me. But I can’t jump. My body won’t let me, my muscles contracting away from a leap and hunkering low. I don’t look down to Emma, pinned to her blanket far below. I don’t look down to the water or over to the opposing face. I can’t close my eyes, teetering there on the cliff. I look up, into the empty shell of the sky. After a moment, I do the only thing I can. I lean into the open.

I lean into the kiss. Hoping it is a kiss. Closing my eyes without thinking. Feeling my body tilt forward slowly, my calves tightening, my toes curling. My heart is racing. I can feel the pulse in my palms. There’s the strange sensation of the whole of my body at once, as a single arching motion. There’s the interval when I’ve gone too far to stop. I hang there, caught upon some invisible notch in the air.

The world narrows to a singular moment and overcomes me. There’s no separation, nothing to distinguish the world around me from who I am. We are exactly the same. I move through space in all directions, outward then back again, dragging the world with me, dragging it into me, pulling in as much as I can just before gravity takes me.

Closing my eyes, I follow a narrow thread of warmth to the glance of her skin then the damp exhaustion of her body shading toward mine and our lips find each other. I open my eyes, hers are open too, and we don’t touch, we don’t speak, we follow the rhythm our lips dictate, slow and soft, a caress diligently finding itself. It’s something we watch from a slight distance as it gathers shape before us, our bodies balancing at the point of contact like a pendulum magically arrested in its widest arc.

Emma’s hand comes to my face, the back of her hand warm on my cheek, and I lean further in, my hand rising from the floor to her bare shoulder. She tilts her head, lowering imperceptibly. I press my lips to hers. I feel her breath on my skin, the beer, the coffee, the chips, and something deeper at the base of her neck. My hand slips between her shoulder blades and her body gathers around it. I slide closer. She relaxes into my hand and we drift for a moment before she folds and I fold with her.

I arch into the open space. My toes leave the ledge, thrusting away at the last instant.

“You fell asleep,” I kidded her, years later. “The end of our first kiss and you were dead asleep.”

She chuckled, her hand snaking through the bedclothes to find mine. “I remember your arms around me, the last lines of that song. That’s all. What was it, four in the morning?”

“Something like that.”

“You were so sweet that night. Gentle, like you’d nearly vanished. When I woke up in your bed the next day, I wasn’t frightened or nervous at all.”

We were cocooned in our morning warmth, our legs and arms sliding over each other as we delayed the moment of leaving the bed. I turned toward her, eyes glazed with sleep.

“Terror,” I told her. “That’s all it was. I couldn’t catch my breath. I’d close my eyes now and then, just so I knew where I was.”

I’m standing at the foot of the bed. I don’t know what to do with my hands. Afraid to move, I let others rush around me. It’s a moment between breaths, extending to the instant Emma looks up to me, propped finally on the pillows, her hair damp, sweat trickling from her chin, her face radiant. The moment she looks up to me and gently calls me over.

“Johnny, come and see.”

And Maggie is there, quiet against her breast, her face finding itself after the effort of birth. Wisps of hair slicked to her head, eyes closed, tiny lips whispering.

Emma lifts her hand and I take it, sliding onto the bed beside her. She’s blazing, heat baking off in red waves, rising into my face and cradling the baby.

I can’t tear my eyes from Maggie. Her tiny fingers curling and clutching at the air, her tender cooing sounds. She finds her shape along Emma’s body, fingers pawing gently at skin, legs pumping beneath the thin blanket, lips working out a new language.

Emma drops her damp cheek to my shoulder and her body follows, her weight collapsing into mine, her heat pushing through my clothes. I can’t make out anything past the edge of the bed. The room is very far away. Emma calls my name again, softly, but I can’t turn to her; I can’t move at all.

“She’s…”

Maggie opens her eyes. Her irises a deep blue, her huge pupils gray and translucent pools. She opens her eyes into mine and I flicker out.

I open my eyes in empty space, leaving the ledge with a push. My breath burns away and I am light, waiting, with no more substance than a leaf at the reach of a spider’s thread. In this pause I’m thin and transparent. I could be that leaf. Or a sail, billowing full.

I close my eyes and I find the fall. I hear the rock wall skim past. The rush of the quarry rising up. My body tips and lengthens, extending itself into the descent, arms out at first then closing together. A swarm of air and a coolness.

I can feel the still reach of the glassy water rushing toward me. I know if I open my eyes I could watch my body plummeting toward itself, tumbling loose from the blue sky.

Emma’s smile breaks wide. “What are you laughing at?” she asks, her voice hoarse with exhaustion, her smile curling to one side in a private, intimate gesture. And I smile too, not knowing what to tell her, not realizing I’d been laughing.

The water bursts over me with a roar and a sudden hush, blotting away the light. The shock snaps my body into place around me. I’m thrown deep into the lake, momentum pressing hard, the water growing colder in the descent. I open my eyes but see nothing. I tunnel into the dark.

Finally, I drag to a stop, my lungs aching. I hang in the interim just before rising, before the pull of air and the cloudless blue sky draw me back.

I fall again, upward this time. I’m laughing in the fall. Emma hears my laugh, her body sloped into mine, her breathing shallow and quick. She squeezes my hand. She laughs too.

Afterward, I’ll try to make sense of it all. From the swim and press and hush. From the flutter of memory and what lingers in my flesh. I’ll place everything in a proper order, singular tiles set into a new mosaic. Afterward, it might all become a single story.

Now, everything happens at once. I rise from the dark toward Emma and the blanket. I break the surface with a deep and gasping breath.

Steve Mitchell has published fiction in The Southeast Review, Contrary, The North Carolina Literary Review and The Adirondack Review, among others. His short story collection, The Naming of Ghosts, is available from Press 53. He is currently completing a novel, Body of Trust. Steve has a deep belief in the primacy of doubt and an abiding conviction that great wisdom informs very bad movies. He is open twenty four hours a day at:www.thisisstevemitchell.com