If Ponce De León could search for the Fountain of Youth, could an Armenian daughter demystify the elusive Iskiri Hayat?

Hidden away in my parents’ home in New Jersey is an extraordinary liquid in a glass decanter shaped like Aladdin’s lamp.

Tinted like a carnelian gem and with a spicy, musky, transporting scent, this exotic liquid seemed destined to be applied like perfume rather than consumed like a beverage. The liquid only emerges from its cabinet to be carefully meted out for honored guests or as a folk remedy for the odd illness.

Enter the rare and precious Iskiri Hayat. Persian for “the elixir of life,” this tonic has been a source of curiosity and admiration since my childhood—a cryptic key to a fascinating past.

The word iskir is a dialectical variant (Turkish corruption) of the Persian iksir (elixir). Hayat means “life” in Persian and Arabic. And from the veneration with which the beverage was spoken about and handled when I was a child, I was convinced that Iskiri Hayat had mystical properties.

Dèdè (my paternal grandfather) knew our Armenian ancestors concocted this liqueur in their native land, but not much else—other than that one whiff had the power to transport an inhaler from exile all the way back to our native province of Dikranagerd (present-day Diyarbakir, Turkey).

I once got a glimpse of the raw ingredients, each preserved in a cloth sack tied with string. Some of them—what looked like clusters of horsehair, or a bunch of petrified raisins—could have populated a witch doctor’s medicine bag. When I was old enough, Hairig (my father) would reel off the 20 ingredients of the liqueur to me in reverent tones: Amlaj, Kadi Oti, Koursi Kajar… Recited in succession, they sounded like an incantation. In fact, as an adult, I learned that Hairig regretted not asking Dèdè more about “the medicines”—what Dèdè called the herbs and spices comprising Iskiri Hayat.

On his last visit to Beirut in the 1950s, Dèdè returned with a batch of the ingredients given to him by Manoush, one of his three sisters. Illiterate, she prevailed upon her nephew, Vahan Dadoyan, to take dictation and write in Armenian script the name of each ingredient on a tag that would be affixed to each item. As was customary for that generation, women knew recipes by heart and gauged ingredients atchki chapov (by eye). Thus, Manoush did not identify any measurements.

Fortunately, Dèdè possessed a dry mixture of ingredients already combined. We don’t know where he got it, but Hairig had, since the 1950s, repeatedly used it to make the drink. Today, our quantity is scarce and the potency of those mixed herbs, roots and spices has been depleted. Only one bottle of Iskiri Hayat remains. This has only intensified Hairig’s mission to decode and recreate the family recipe for Iskiri Hayat.

How could my father, in the 21st century and far from his ancestral homeland, reconstruct the recipe when he didn’t even know the English language equivalent for the names of some of these captivating-sounding ingredients, nor how much of each ingredient to dispense?

Alas, like the melange of spices and herbs in this ethereal concoction, many of the ingredients’ names themselves were probably combinations of languages spoken along the Silk Road, including the Armenian dialect of Dikranagerd, Arabic, Western Armenian, Kurdish, Turkish and perhaps even Chaldean Neo-Aramaic. Even for someone like my American-born father, who was fluent in the dialect of Dikranagerd and possessed more than a dozen dictionaries for the languages in question, trying to make sense of some names was problematic.

He knew that Sunboul Hindi was Indian Hyacinth. And that Manafsha Koki was Violet Root. But what the blazes were Agil Koki, Houslouban and Badrankoudj?

So much was lost in the genocide. To cut the Gordian Knot for an Armenian of the diaspora is to locate his/her confiscated, ancestral house in Western Armenia. Since Turkish authorities deliberately changed regional names and landmarks after 1915 to obfuscate their Armenian origins, the directives (often descriptions of the house and surrounding areas, handed down verbally from genocide survivor ancestors) are today insufficient.

For Hairig, another vexing quest had been to find people, of Dikranagerd ancestry or otherwise, who could help him decipher the names and meanings of the elusive ingredients in Iskiri Hayat. Though the famous Cookbook of Dikranagerd possessed a recipe for Iskiri Hayat, it was not the formula he sought. And while some firms produce commercial formulas, he wanted our specific ancestral recipe.

While the task seemed insurmountable, my father had made some progress over the years. However, in recent times, he seemed to have exhausted his options.

So, when I decided to make the pilgrimage to the deserts of Der Zor—the killing fields of the Armenian genocide—last year, I hoped to extend our search to Haleb (Aleppo, Syria), where some genocide survivors (including my relatives) found refuge. There, I surmised, the right person would surely recognize the ingredients’ names, know what they looked like, and even point me to where I could obtain them. We could worry later about how much of each item to blend.

Ultimately, my aim was to refresh Hairig’s supply—and from a source logistically close to Dikranagerd. Doing so seemed a meaningful thing a grateful child could do for a devoted parent in his twilight years.

My father had never seen the home of his ancestors and, yet, he carried the ham yev hod (flavors and fragrances) of Dikranagerd in his words, thoughts and deeds—from his modesty, humor and hospitality, to his dialect and storytelling ability, to his culinary and musical aptitudes. A humble gift would be to help him make that remarkable elixir that could, at least emotionally, bring his ancestors, their way of life, and our lost homeland back to him. And was it not worth it to rediscover a missing and precious part of our culinary heritage, and perhaps share it with the world?

During those fleeting days I spent in Haleb and through fellow traveler Deacon Shant Kazanjian (another Dikranagerdsi—a person hailing from Dikranagerd), I met and quickly bonded with Talin Giragosian and Avo Tashjian, a married couple who possessed the fine qualities one would wish to encounter among Armenians. Talin also happened to be Dikranagerdsi, and it stirred the senses to hear her and Deacon Shant converse in our earthy, colorful, near-extinct dialect. Talin, an English teacher, tried her hand at translating the Iskiri Hayat ingredients we did not recognize, and even enlisted her mother’s assistance. However, they both were as baffled as my father had been over the virtual hieroglyphics. And with that, Talin and Avo met me at the famed covered Bazaar near the Citadel of Aleppo, where the passageways are said to extend from the Fortress all the way to the Armenian Cathedral of the 40 Martyrs in the Old City.

This underground marketplace was a reminder of what life was like centuries ago. Rather than seeming anachronistic and backward, the atmosphere was invigorating. The Bazaar lured visitors to connect with history by showcasing cultural features that had managed to remain intact despite the modern world’s creeping influence. Here, people were not “living in the past,” as some are inclined to say about those who don’t conform to modern habits. These people preferred to cling to their traditions, taking part in an authentic continuation of the past in the present.

As we entered the Bazaar, we marveled at the vaulted ceilings, the intricately carved doors and metalwork on the walls. Merchants — some wearing kaftans, others in Western dress — would call out to customers. Through the narrow, serpentine passageways, hired hands led donkeys carrying sacks of grain. Others carried supplies on horseback. Niquab-wearing women haggled over prices. Through the labyrinths, we passed through the jewelry, textile, pottery and camel meat districts, until we finally reached the herb and spice district.

Talin directed me to the stall belonging to the Spice Man of Aleppo. He was the eldest, best known and most amply supplied of the spice vendors. Talin surmised that the Spice Man, who inherited the business from his father and grandfather, retained the knowledge they had amassed and transmitted to him. This would have meant that when our ancestors emerged from the deserts of Der Zor speaking a variety of dialects, the Spice Man’s grandparents picked up the many names a product went by, including those used by the Armenians.

In spite of whatever their personal ambitions may have been, the Spice Man’s four sons all worked in the family business, operating out of a closet-sized stall. It was teeming with bottles, packets, canisters and jars filled with powders, liquids, seeds and roots. A ladder led to a trap door on the ceiling that opened into an attic, their main storehouse.

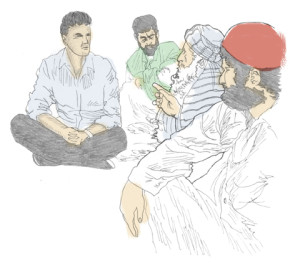

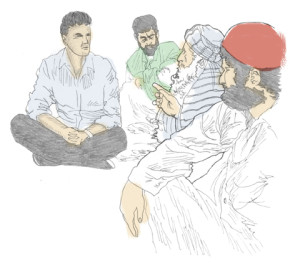

Unable to communicate with words, I still could not contain my zeal upon encountering the Spice Man. Stoic and world-weary, he had no inkling of or interest in the source of my enthusiasm. A man of few words as it was, the Spice Man did not speak English. But as Talin recited the shopping list to him, name by name, something incredible occurred:

“Do you have Agil Koki?”, she asked in Arabic.

The Spice Man gestured a grand nod of the head, like a solemn bow, to signal “Yes.”

“What about Badrankoodj?”

Again, the Spice Man’s head would slowly move from up to down until his chin brushed his collarbone.

And so this ritual went on. Talin would say a name, and the Spice Man would unhurriedly acknowledge that not only did he know what the word meant, but that he stocked the desired item.

Then, the Spice Man would call out to his sons to each fill different parts of the order.

By the time Talin was through, we had collected all but one of the ingredients on the list. Even if he were not interrupted by demands from his customers, the Spice Man still would not have been inclined to have a significant chat. We were neither able to cajole him to explain in Arabic some of the more esoteric terms, nor did Talin recognize mystery ingredients by sight or smell. However, the Spice Man’s sons did write down, in Roman letters, each ingredient’s name on its corresponding package—a revealing moment.

I was in mortal shock when we left the stall having completed the lion’s share of my mission. To celebrate, Avo, Talin, Shant and I went to the Bazaar’s bath oil and fragrance district and rewarded ourselves by purchasing traditional kissehs—the coarse washcloths used by our elders.

Back in my hotel room, I shed a tear while inhaling each aromatic ingredient. Then, I securely packed them into Ziploc bags, distributed them throughout my luggage, and hoped I wouldn’t be taken aside at Damascus airport for suspected drug smuggling. Even afterwards, the heavenly scents that clung to the clothes in my suitcase made my mouth water when I unpacked them back in the States.

What was Hairig’s reaction when I returned to New Jersey, told him my tale, and presented him with one packet after the next? He seemed gratified, but also at a loss. Were we really that close to our goal? It was almost too remarkable. He inspected each sachet carefully as if to say “So this is what Badrankoodj looks like!” and braced himself for the next step: finding a knowledgeable spice vendor who could give us English equivalents to foreign words with the help of visual stimulus.

From here, we will keep readers apprised of the last legs of our intoxicating voyage. The reconstituted beverage may indeed be so supernatural that the next time you hear from us may be from Dikranagerd itself.

Lucine Kasbarian, writer, political cartoonist and book publicist, has been immersed in book, magazine, newspaper and online publishing for more than 30 years. She is a descendant of survivors of the 1915 Turkish genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians and Greeks, which drove her grandparents from their native lands in Western Armenia (now within the borders of Turkey). Lucine is the author of Armenia: A Rugged Land, an Enduring People (Simon & Schuster) and The Greedy Sparrow: An Armenian Tale (Marshall Cavendish). Her syndicated works, often about the culture of exile, appear in media outlets throughout the world. Visit her at: lucinekasbarian.com

Elixir in Exile first appeared in The Armenian Weekly.

Read our interview with Lucine here.