Back to the green tiled wall, I watch the surgeon apply clamps to a patient’s fingertips. Unrolling a length of gauze, he winds it through the clamps and then the loops of a cloverleaf mounted at the top of a metal pole. With one pull, the arm is lifted. In a blue hairnet, blue shoe covers, a mask, and a giant white onesie—a “bunny suit”—it looks as if a cloud swallowed me. When I modeled it earlier for the patient in pre-op, they laughed, asking if I was married because my husband would certainly find the sight of me hilarious.

From an uncovered leg, a long, rectangular strip of skin is peeled away with a tool that looks like a potato peeler. Surprisingly gray, the skin is dropped into a stainless steel basin filled with sterile saline. A resident removes it and passes it through a device that looks like a pasta machine. The resulting skin mesh is applied over an injury that was prepared by washing, cutting, and cauterization.

Under my bunny suit I wear bright red scrubs that mark me as a nursing student. Thinking of my students in the creative writing classes I taught only last spring, the list of what I have lost runs through my mind: my house in Texas, my poetry and art books, my cat, my cameras, my marriage, my job as a lecturer of creative writing. This is the second surgery I have witnessed at the university hospital and when the arm is finally lowered I think not, Why am I here in an operating room? But: How did I get here?

“You’ll be the one who’s blamed,” my therapist says. “The one who left.” In Texas I found my way to her office more than four years ago after an outburst of frustrated anger during an argument with my husband left me shaken and unmoored. During our sessions I learn that expectations of people in our lives are “premeditated resentments.” Outside her office, my reading of Buddhist practice teaches me of the option to have no expectations, which feels like trading the twins of hope and despair for a flat, lifeless line.

The closer I get to my husband, the more I lose my frequency to a fog of static, and so when I return to Austin from Ohio on semester break I stay at a hotel. At my therapist’s office I comment on the new landscaping. Pale, heart-sized river stones now line the space between her office and the next building over. “I was worried the deer would be unable to navigate these rocks,” she says. “But they aren’t having any trouble.”

As I stumble through a new state of re-positioning my life over a Mid-western landscape, the metaphor of animal experience continues to appear. Through late summer and into fall, geese come and go from a pond near my apartment. But one remains, swimming, eating grass, honking at intervals when I walk past with my dog. A lone heron stalks along a small creek and I wonder if the two birds find any company in one another. Is the goose injured? Mourning? Two days later the goose is still there, maybe: there are now six geese, all standing and eating, and I cannot tell if the possibly heartbroken goose is among them.

Synchronicity is unconcerned energy. It does not ask what you imagine of the future: Who you will marry, where you will live, if you will have kids. What I experience in leaving Texas for Ohio is not serendipity, that fateful pull a friend and I recall as having too much influence over our younger lives when we wanted to believe everything had a meaning to decipher. Synchronicity is worrying over my accumulating out-of-state student debt and the emotional cost of my destabilized marriage, and in moments of peak anxiety looking at the clock on the stove, the car stereo, or my phone, to see the time as 4:44 or 3:21 or 11:11 or 12:34. On some plane—mathematical, chronological, invisible—I am walking the right track even when most days feel like a series of falling overs as I learn how to take blood pressures, how to assess levels of consciousness, how to cleanse and pack a deep wound.

Usually I do not turn on the TV during the day, but when the Kavanaugh hearings are aired, I take a break from studying pathophysiology to watch. For the second time, I have left a marriage to a successful man. Again, I see how easily people—female, male, gay, straight—take sides on a split and how commonly they lean towards power. Sometimes knowing yourself means being alone with yourself, means letting go of everyone you thought you loved and who you believed loved you. How did I know my marriage was over? Not while sitting in Al-Anon meetings struggling with my desire to fix the unsolvable. Not when I convinced my husband not to throw me out of the house by having sex after another argument that escalated. Not when I scanned his cellphone text-log in the years before, and the months after, I left. When we are still speaking, he recounts another encounter with a tearful female student who thanks him for making her feel safe in class. Over the phone, I feel him glowing. It takes a month of not speaking to him to wonder why making me feel secure was not his priority.

How I know: Another month passes and I begin to wake up happy. Or what registers as a close approximation to the feeling as I begin to live without daily storms—mine and his—crashing through my life.

To save what I can, I buy most of my furniture at Ikea, unpack it in the apartment parking lot and carry it upstairs, piece by piece. The couch, however, I have delivered, and the men who carry it in are friendly even in the rainy later-summer gloom. After they maneuver the box into the living room, one guy looks at his hands, covered in mysterious black dust (which soon covers my own hands, as I begin to cut the cardboard away from the couch), and instead of shaking my hand bumps my forearm with his own. He’s a type, the sort of guy I see in Ohio—skinny white guy with piercing blue eyes, tattoos that cannot be hidden, a missing tooth or two. We are ground zero of the opioid epidemic; men who perform manual labor are stuck the hardest. These blue eyes I see later in the semester in patients who lose significant amounts of skin and muscle tissue, possibly from injecting drugs. I attend a training session where I learn how to administer the antidote to opioids, a drug—naloxone—that rips the high right out of the synapse. “Don’t expect a thank you,” the organizer warns.

Over the past years I have struggled with my own addiction to believing I have the answers and to the belief that making enough effort guarantees success. With this sometimes self-destructive desire to help comes a corresponding addiction to men in pain. Men who blaze and require a continual re-application of fuel. When I first met my husband, his attention was a fire unlike any I had experienced. Passionate letters, gifts of books and jewelry, calls at all hours. It did not register then that there was someone else—or several someone elses—building the heat from the other side. That the circle would shift and I would be the one not pursued, but sustaining.

Earlier in the semester I witnessed my first surgery while wearing another bunny suit. Watching the process of removing pins from bone, I learned they can be closer to the size of writing instruments than sewing needles. When the patient awakes in the post-anesthesia recovery unit, they appear disappointed to find a wound vacuum—designed to speed healing—in place. Before I can catch myself, I say, “I’m sorry.” But I do speak from a kind of experience, years ago having seen the same sadness on my husband’s face when he woke from anesthesia with this very device tethered to his body.

What got me into therapy and then into Al-Anon in 2014 was a wooden spoon. I was cooking, my husband and I exchanged words, I threw a spoon and it hit him in the chest. This isn’t you, my nurse practitioner said. See this therapist. I made an appointment. As I moved into my later thirties I began to see how anger ruled me, how it was a legacy passed to me, how trying to avoid anger only made it grow. Yet I also saw how women were not allowed to be angry, in the world or at home. With reason, or without.

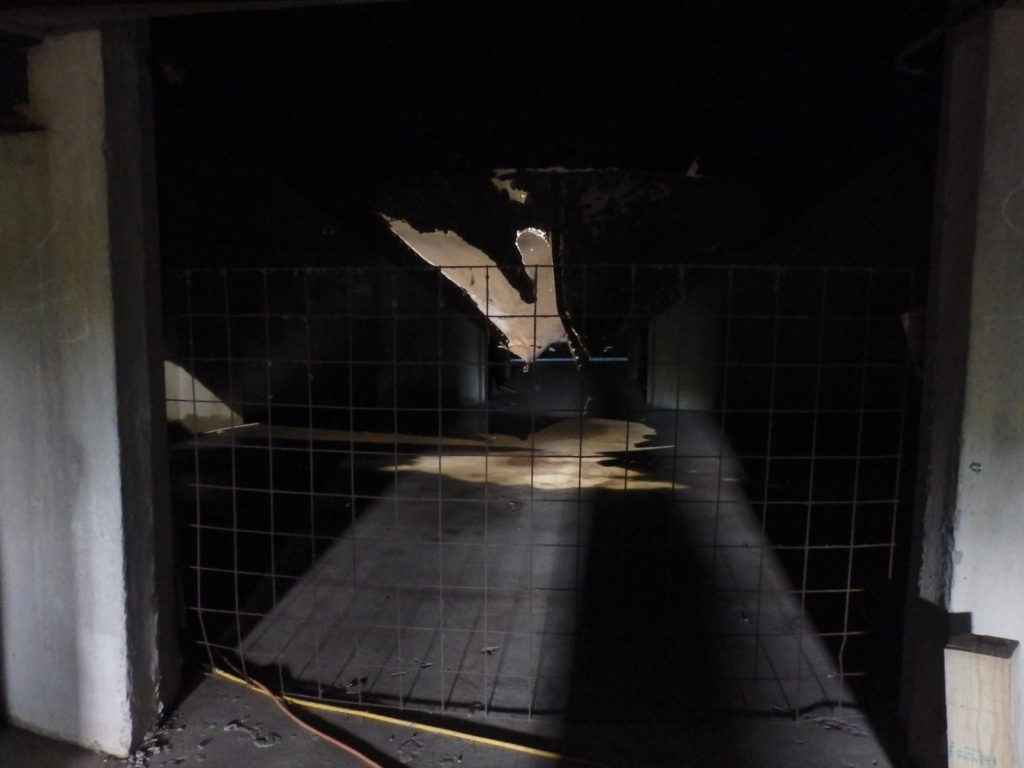

A central tenant of Al-Anon is that in focusing on the self, by stepping back from the urge to control and monitor the behavior of a loved one, a positive change can result in the relationship. I found the gains, in terms of the health of my marriage, to be one-sided. Maybe every relationship is meted a set amount of certain things. The less I drank, the more he did. The less I lashed out, the more furious he became. Living with chronic anger and alcoholism—whether yours or someone else’s—is like walking on the surface of a funhouse mirror. It is a destabilized, warped landscape.

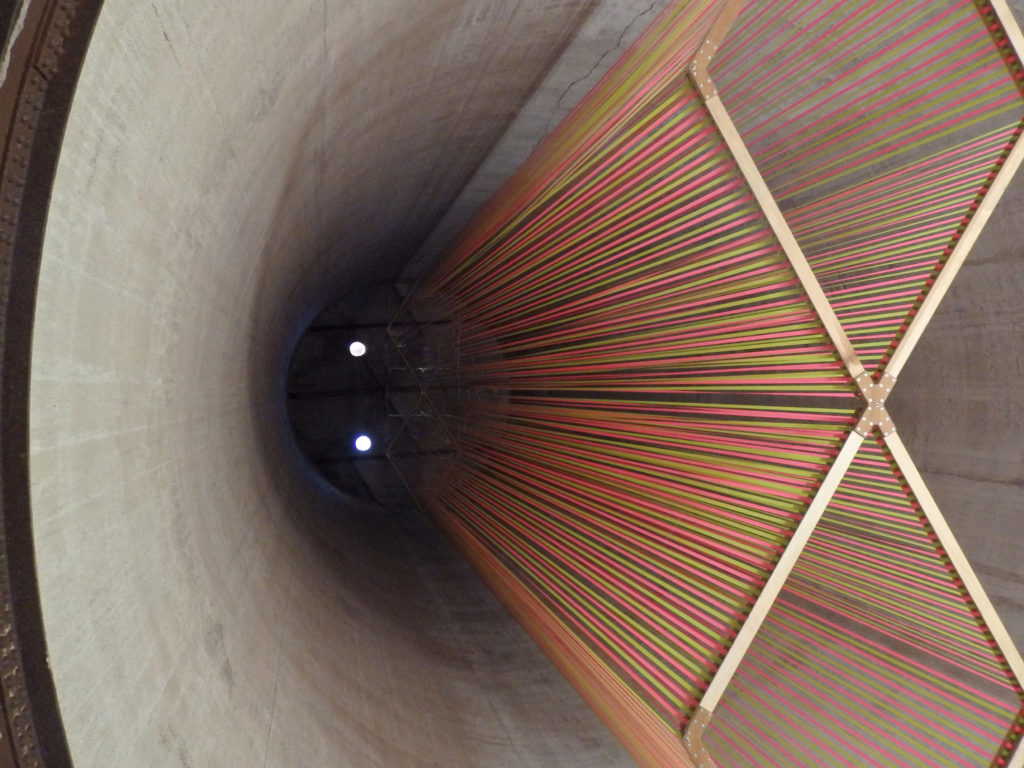

I have read that life is one long room, containing everyone who has played a part in your journey. It is not just the people in the space, though, it is the spaces themselves: the yellow kitchen in my house in Austin, the church basement where I first went to Al-Anon, my office in the English department at UT, my apartment office in Ohio, the patient rooms and operating rooms I move through in school. It is the women I worked with at the mental health clinic at twenty-two, connected to the post-surgical wound care I did for my husband at thirty-two, connected to the patients I cared for with skin infections and burns at forty-four. It is the North Carolina house I grew up in, the upstate barn I lived in for a New York winter, the red house my husband and I rented for several consecutive summers in Berkeley. It is this last house I keep our marriage in, a space in which we were happy, where Pacific coast fog drifted through the cypress trees every afternoon.

How I got here: My aunt died and left enough money for me to envision paying for at least one semester of nursing school, wherever I was accepted. Although I loved teaching I was not prepared for the politics and leveraging required of academic life. I wanted to love a job and to be paid a living wage. To not be caught in the current circumstances of the artistic economy. Becoming a nurse practitioner was a dream I put to the side while I earned an MFA. As nearly every week my husband threatened to quit his job, it seemed that if I wanted a safe place to write, psychologically and financially, I would have to make it myself.

When my sister and I visited our aunt in France, the winter of her death, we remained neutral in our expressions as she showed us her house in Bram sitting within sight of the highway rotary. It was a world away from the medieval battlement she and our uncle spent years repairing, in Banyuls with the Mediterranean in view, where a large lizard roamed the walls, where my uncle sat on the patio under the jasmine drinking boxed California rose like the Americans he professed to hate while the hunters tracked wild boars through the vineyards. Now my aunt’s head was swollen to twice its normal size due to radiation treatment for lung cancer that had spread to her brain, her blonde hair long gone and replaced with a crooked wig and worry about her pets. After our week’s visit at a rented country house, we returned her to her home and husband, promising to see her again even though it was unlikely. As we moved through the door I turned to see her face, knowing we were leaving her the only place we could, a place of her making, one of writing, travel, alcohol, and anger.

In my apartment hang two pictures, one of the house in Banyuls and the other a charcoal of nearby Collioure. These I crammed into my car before I left, before I pressed on and did not heed my husband’s pleas to return. This stings: I chose not to turn around. To not go back when he asked. Perhaps this is another addiction, to pushing through. But a life cannot be made in an avalanche. I released as much as I could in an attempt to level the land, but when he drained the bank accounts over several years I had nowhere else to go but away. I could use my inheritance to bail him out, or to shore myself up.

Recently I read a report from the CDC about suicide risk and occupation. Among men, those who work in manual labor—men who deliver furniture, men who build apartments, houses, offices, and hospitals in booming Austin and Columbus—have the highest suicide rates. Among women, those who work in the arts are the hardest struck. I cite the statistics not to imply I was suicidal, but to illustrate the importance of realizing there are choices women can make that will provide an option other than enduring. My husband and I are both writers and artists and we had a system that worked, one that I could depend on, for a while. Teaching requires the control of emotion, response, and expression, as does recovery. But it is impossible to hold everything in: My marriage fell apart when I began to teach at UT for much less than he made, and the self-management I had to do to survive bled over into my creative life. He kept writing. Living in a life of compartmentalization and blinders, I nearly stopped.

A relationship ending is being lost from what was, and if there is anything to hang onto it is the connection between how things were and what they will become. The space between is far from empty. In one of my first Al-Anon meetings, someone said it is not how far you have to go, but how far you have come. My apartment windows face a wooded area. Now that the leaves have fallen I can see the empty swing sets in the backyards of the houses in the adjoining subdivision. Hanging curtains would interrupt the light moving in and out of the windows. I am not sure how I feel about waking up happy; about not living around the drama of another person’s choices and in the safety I found in living apart from myself. In my bunny suit, I take steps, some giant and some small, and learn what I can from where I end up, from the people I meet, from how I navigate—successfully or not—the hazards and confusions of the daily human condition. Our stories, our lives, were connected, but even in marriage they were never the same.

Commenting on the absence of female road narratives, Vanessa Veselka writes that when women on journeys are encountered, they are not asked, “Why are you doing this?” but, “What thing happened to you to make you want to go off on your own?” As time passes I continue to discern the difference between being reactive and having a reaction. A reaction can take time; it does not bear the expectation of immediacy. Staying in my job in Austin, taking prerequisite classes for my applications, going to therapy, sleeping on the couch or asking my husband to: those were reactions to living in a marriage I could not rescue.

How did I get to here from there? I learned to ask for help: how to frame a difficult conversation, how to make it through the holidays alone, how to remove my spouse from my car insurance. When it was offered, I learned to accept it: non-skid grippers for my shoes to prevent falls while walking my dog in the snow; notes from a missed lecture; calls and texts from friends who continue to check in.

In my mind spins a loop of all I have gained: space, loneliness, my eyes steady on my own in the mirror when I can finally look at myself again. Moving states has not removed me from anger, but it has decreased my reactivity. If, as Virginia Woolf wrote, there is a line running through each story to which everything cleaves and cleaves—runs to and runs from—what is the line coursing through this layered breakage and regeneration? As winter moves in and it is colder and darker earlier every evening, I walk past the pond less. The last time I see the goose it moves from the bank into the water as my dog and I come closer. This bird is not the woodpecker I found the week before I left Austin, lying on its back on the dog bed we kept outside. Not the woodpecker that clutched my finger with its feet and pecked at my hand, refusing a perch on a branch and instead settling into a stockpot lined with towels. That was small enough for me to catch and hand over to someone else. Synchronicity is not about how things will turn out, but how life carries on while we adjust.

“How do you like Ohio?” A woman asks as she scans my groceries later that day.

“It’s gray, I say,” surprised I miss the sun.

Laurie Saurborn is the author of two poetry collections, Industry of Brief Distraction and Carnavoria, and a chapbook, Patriot. An NEA Creative Writing Fellowship recipient, her work has appeared in publications such as jubilat, storySouth, The Cincinnati Review, The Southern Review, The Rumpus, and Tupelo Quarterly. Previously, she taught creative writing at the University of Texas at Austin, where she directed the undergraduate creative writing program. She is currently pursuing a graduate degree in psychiatric mental health nursing at Ohio State. Find her at lauriesaurborn.com.