Barbara Ewell: I really like your poem For a Long Time. I like watching change come over the speaker even before it happens. The waiter and the bartender don’t know what the reader does – – how she’s going to move once she leaves that place. I think I have told you before that I love the way you bring me into the scene in your poems- – and in your fiction, too. You let the reader participate, oftentimes more fully than the other people in the piece. Does that make sense? Do you know you’re doing this? It’s as if you’re telling the reader little secrets, like an aside.

B. Chelsea Adams: I don’t consciously think about allowing the reader to participate in my work or about telling the reader secrets; though I’d like to do both. My more selfish motive is that I want to step into the place or situation I’ve created, to breathe the air, step on the grass or gravel, touch the tree. So my motivation is to imagine a place and then to be there, to know what the place is like, to know what the characters are up to, to hear their voices.

BE: You say you are “owned again” by the music. And that audial image wraps itself around you and becomes vapor-like cloth. Caresses the skin. Is that how it “owns” you?

BCA: In a way. For me, music isn’t just about listening. It fills me up and wraps around me, takes me over on the outside as well as on the inside. It sets me moving. Whenever I’m at a concert, I can’t sit still. I look around at the audience, and wonder how some, maybe most, people aren’t moving at all. They sit so quietly. This mystifies me.

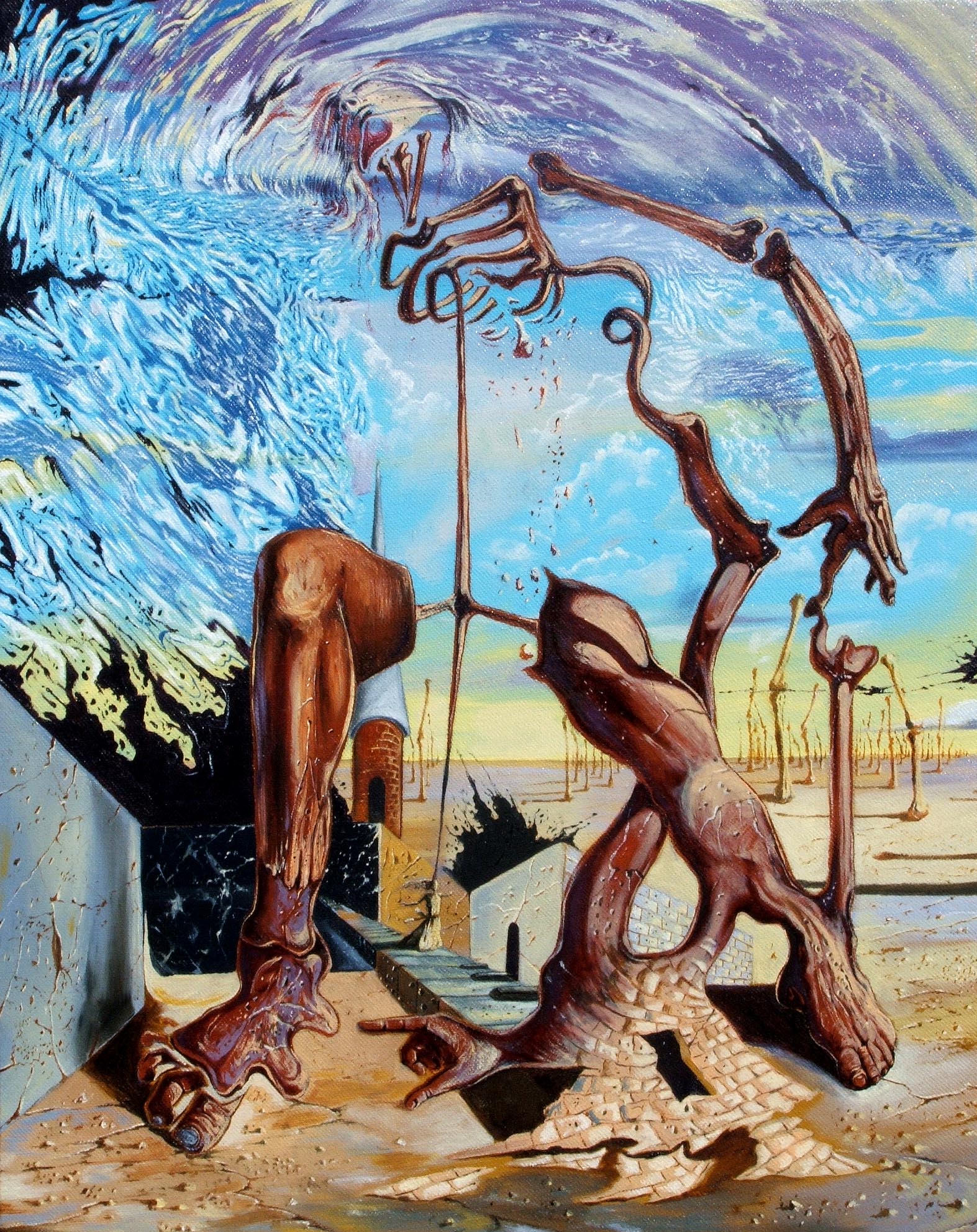

BE: The way sound becomes touch in your verse takes me back to Darwin Leon’s accompanying artwork, The Arrival of the Goddess of Consciousness. The poem does bring about an awakening to the consciousness of the senses, of joy— if that makes sense. Do you like the selection?

BCA: I love Darwin Leon’s artwork. I wondered if Mary Akers picked it because of the way the goddess’s flowing fabric is similar to the silky scarf in my poem. I thought too about how the power of the goddess could be compared to the power of the music.

When the goddess arrives, buildings topple; in my poem when the woman finally hears the music, the heaviness disappears, and she can sing to the moon. (The buildings collapsing, and just the look of them, made me think of the deck of cards in Alice as she wakes up back on the riverbank.)

BE: “For a Long Time” is a poem about music, about jazz. I know you love music, but I don’t know how it plays into your creative process. Does listening to music make you want to write? Which comes first, the horse or the cart? The listening or the writing?

BCA: Sometimes the music inspires the words and sometimes the words find their music. The words most often arrive as a phrase I can’t get out of my head. The phrase often comes in silence, on a walk, driving the car with the radio off, sitting on the porch looking into the woods. The phrase keeps repeating until I hear the next line and start to discover whose talking, and where their words are taking me. When I get stuck and can’t find the words that come next in a line or a sentence, I try to find out what music or rhythm is needed. I kind of tap or drum it out. Is it anapest or iambic pentameter? Does it fit the melody in John Lennon’s “Imagine,” Ellington’s “Take the ‘A’ Train,” Ella’s singing of “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” or the tune my husband, a musician, is playing in the other room?

BE: A lot of your poems have the speaker remembering voices. Voices from childhood games and fairytales, like in the Hopscotch manuscript–from lovers and children–as in At Last Light. You use a similar technique in Looking for a Landing and in the Java Poems. So my question is, are those really tapes? Do you “hear” voices, so to speak?

BCA: The voices are always there just at the edges of things. In one poem I wrote, “Parallel Existence,” a speaker is sitting with friends at the same time she is in a memory, hearing voices from the past. Fairy tales, nursery rhymes, and favorite poems are also like songs, tapes in my head. I can’t memorize my own poems, but I have memorized these tales and rhymes from childhood and many songs.

BE: I noticed that several of the writers already interviewed talked about recovery as a theme in their work, as it is, of course, the main theme in r.kv.r.y. Do you see it as a focus in your writing? Is your writing guided by themes? This is another one of my horse and cart questions–which comes first: theme or poem?

BCA: When I first learned about r.kv.r.y, I didn’t think I had written any poems about recovery. But when I went through my work, I saw “For a long time…” and “Music Therapy,” poems where music saves a woman. Then I realized that many of my gardening poems fill the same function; many are poems of healing. And now for the second half of your question, what comes first, theme or poem? For me, the poem comes first or maybe just the phrase, the line. I never know where I’m going. I believe that discovery is what creates the joy of writing. And somewhere in the discovery the theme is found. But certain themes repeat in my work, nursery rhymes and fairy tales that I see speaking to the present, stairways and gardens that help one find oneself, or one’s place; jazz and coffee where I celebrate my addiction to their sound and taste. I’m sure I have other themes in my work as well, but these are obvious ones.

BE: I think every writer I have ever known personally, as well as the ones I have read about, says that their writing began in secret. Oddly enough, as long as we have known each other I have never asked you how you started to write? And why, if there were a why?

BCA: How I started to write; I know it has to do with my mother, grandmother, and my mother’s sisters. They talked about books, bought me books, brought me to the library, wanted to see what I had written and to tell me how I could make it better. But my father’s family was important too. They told stories, family stories but also stories that were utter fictions, which when I was younger I believed. I loved to hear their stories. You asked about whether I wrote in secret, that did happen, but not until college. I think I became afraid, when I read so many wonderful, accomplished authors, that my work wasn’t as good as those others. I filled my drawers with writing, much like Dickinson. It was getting caught in the act of writing by friends that encouraged me to show my work again.

BE: I already know the answer to my next question, but I’d like for your readers to know as well. And I’d like to know more. You know how I love my computer and do everything at keyboard. And I know you do not. “Cannot,” you tell me. So tell me more. How do you draft your work?

BCA: I write longhand, usually in cursive. I can’t seem to write at the computer, though I do sometimes try. When I try, my writing feels clunky, has no voice. I often give up and begin again with pencil and paper. I think it is the difference in pressing keys down one at a time, rather than letting your pencil flow across the page. It is almost as if the words are in the motion of my hand, not in my mind. I just read back over what I’ve written longhand to answer these questions. Ironically, my first sentences are printed. When I get going, find my rhythm, I go to cursive. My writing also gets messier and messier as I go faster and faster. Writing in cursive where the letters are connected and my hand is making circles and swirls, seems to help my ideas connect, help me find out what I think, help me hear the characters’ voices and find the music in them.

BE: I know how much you value the guidance you received at Hollins finishing the MA. Would you like to elaborate on how the program–or any program–can make a writer out of an almost-writer?

BCA: Part of it is just the confidence building that comes with getting into a good program. But, and I can only speak for Hollins, having faculty work closely with you, having small classes where everyone has the same goal gives you and your writing the attention it needs for you to learn its strengths and weaknesses. And there you are with people who know how to overcome weaknesses, people willing to let you know their secrets. Students also form long lasting friendships with other writers. I cannot say enough positive things about the Hollins faculty and the time and support they gave. Also, we all know we learn from the example of professional writers.

BE: You like to workshop your poems and fiction. I have been in writing groups with you, and you are a wonderful reader for other writers. Do you have any suggestions about how to handle comments from a writing group? Responses can be quite varied.

BCA: One of the reasons I now am part of two writing groups, one for poetry and one for the novel, is that having a number of readers look at your work gives you a variety of criticisms. One reader is wonderful at telling you when your dialogue doesn’t ring true, another picks up problems with logic or grammar, another points out where you need line breaks or more powerful verbs, and another is gifted in pointing out when you need more about an idea or character or when you need to cut something. You do need to know which criticisms to take, and to trust your instincts about whether what they are saying rings true. Of course, if most of them are saying the same thing, it is time to listen.

BE: You are an inspiring teacher who values the craft of teaching. Did you ever have a student say something or write something that influenced your own writing? We both used to talk about how much we learned from students about the literature we had assigned, but did any of their insights ever spill over into your own writing?

BCA: They always helped me remember that we all are beginning writers. Each new piece needs something different. Also, when a piece of theirs wasn’t quite working, and I had to tell them why it didn’t work, I figured out something I could apply to my own writing. For one thing, it reminded me of things to avoid. But the most important thing was sharing the excitement of seeing a piece come together, of knowing they were excited and knowing they were now more confident writers, who had come to love writing.

BE: What do you read? Poetry? Fiction? History, or science? Do you have favorite writers that you always go to? Do you ever stop reading so you can start writing? Would you rather read or write? Or is that a dumb question?

BCA: I mostly read fiction, novels and short stories, but I read my favorite poets’s new books, Margaret Atwood, Russell Edson, Margaret Gibson. And, of course, there are more. I read my writing groups new poems and chapters, read new poets I discover, and read old favorites over and over. I’m also somewhat of a political junkie, so I read books about politics, history, and the environment. I teach the creative writing component of my granddaughters’ home school curriculum, so one of my joys is reading their work each week. I don’t ever stop reading. I know some writers do stop, especially when they are in the midst of a book. But I need to read always. It’s just part of my day, perhaps, an addiction. As to the last part of your question, I’m addicted to writing as well. These addictions keep my days very busy.

BE: What is the role of Poetry in the Whole Scheme of Things? I realized that that’s a what’s-it-all-about-Alfie question, but I would love it if you’d have a go at it.

BCA: I want to say that poetry is at the center of things, but so many people just don’t put it there, just don’t read poems, even poets. I would guess, most young people loved nursery rhymes, Shel Silverstein and Robert Louis Stevenson, maybe even loved poems right up to high school. Then, if they were asked to read Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Donne, and Keats without the necessary tools to understand the language, the time period, and the issues of those times, they felt stupid, but didn’t know why they didn’t get it, or they might have felt bored for the same reason. We need to be confident readers of poems before we can explore poems that we have to work at to understand. When I am doing a reading, and I’m reading stories, more people will come to listen, than when I read poetry. And yet, I believe my poems are accessible. But I am hopeful that poetry will have a renaissance as I see more and more readings, presentation poetry, and poetry slams, sponsored by local groups. In the small town of Floyd Virginia, once a month readers from 80+ to elementary school age read at a venue dubbed the Spoken Word. In Blacksburg Virginia a group has formed that sponsors readings at the local library and at local pubs. And Barnes and Noble in Christiansburg is sponsoring poetry readings once a month.

BE: What a positive note, Chelsea, to close the interview with–and the pun was unintentional. Thank you for letting me interview you.

Dr. Barbara Ewell, an English professor who also retired from Radford, and B. Chelsea Adams have been sharing poems with one another since 1982. They did a reading, where the poems they read were written as a conversation, first there would be one Barbara had written, and then Chelsea would answer it with one of her own. For over 5 years, they participated in a Round Robin with four other poets. Each poet would choose a line from the poet before them alphabetically, and inspired by that line would write her own poem. Years ago, Barbara began referring to Chelsea as her poetry sister.

Chelsea’s most current poetry chapbook, At Last Light, can be ordered from Finishing Line Press.