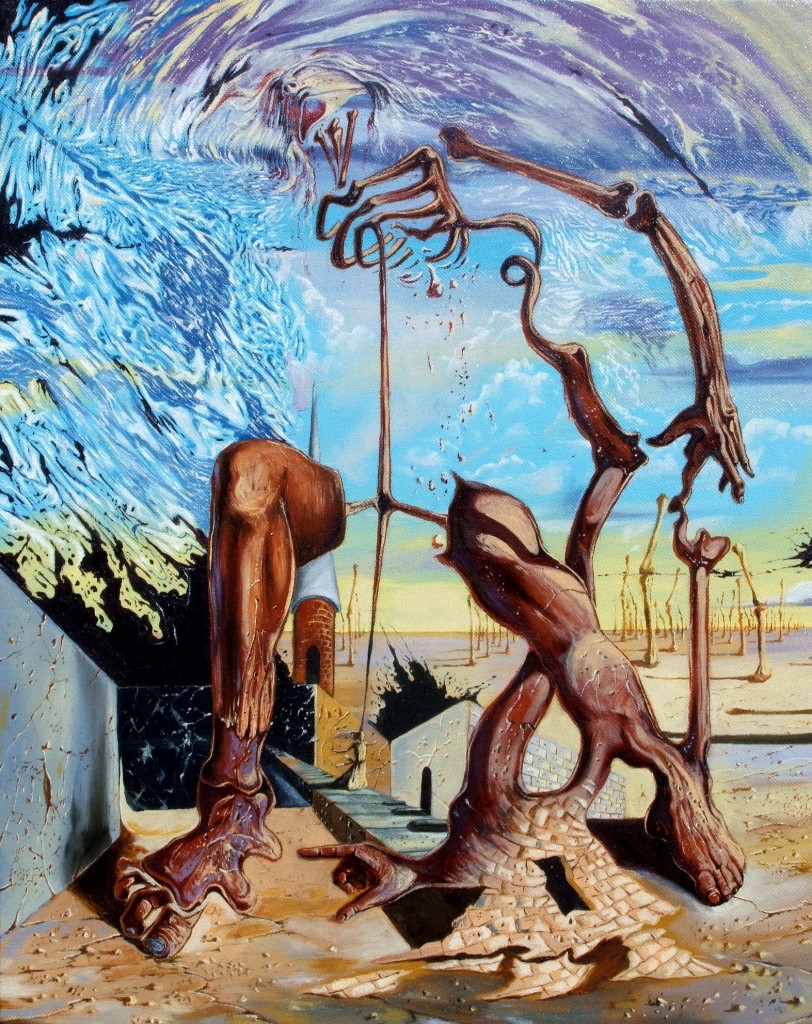

Eye Always Was, oil on canvas, by Darwin Leon.

Prefatory note:

This document was recovered from what was once known as a 5.25-inch floppy diskette. From some earlier century, it’s a black cardboard square that encases a flimsy circle of plastic.

The text documents a primitive video game from a time before people had their own computers. The font and formatting appear to be artifacts from a device called a “dot matrix” printer. A singles bar was where men and women met before the Internet.

We have now advanced well beyond this, but this may have historical interest for those who do not realize that Iphones, Facebook, and Second Life were once not an integral part of daily life. It may also offer insight into a time when we were just human.

Simulators

It looked like any other video game with a screen, slot for quarters, keyboard, and joystick. I assumed it was a game where you shot aliens with blipping dots. I walked to it behind the bar. On its side, it said in big blue letters Date Simulator.

I wondered, is this like women on bar stools in rows and you shoot them with a laser or maybe you chase each other through a series of mazes? The screen showed the inside of a bar: a fern covered a window, the bartender wore a vest, a couple made out in the corner—not a bad parody. I dropped in my quarter.

A woman’s face came on. She smiled. I moved the joystick to approach. I figured it was some sort of joke. I typed, “What’s your sign?”

There was a little electronic squeal and my character melted into a puddle of electrons. Three dollars later, I’d tried “Haven’t I seen you someplace?” “You’re the best looking thing I’ve seen in months,” “Nice suntan,” stuff I’d never say in real life. What kind of machine was this? Finally, I tried, “Hi, I’m Jerry. What’s your name?”

“Ursula,” she said.

“Nice name.”

No response.

I typed, “Come here often?”

Poof, puddle of electrons. I asked the bartender for change.

“Figure it out yet?” The bartender’s nameplate said Tim. He was tall, blond, mustached.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s fun though.”

“You gotten her home?”

I shrugged. “You mean Ursula?”

He gave me the look, the high school gym one when other guys would ask if I’d ever kissed a girl. “I thought her name was Heather?”

“Heather?”

“I just typed ‘What’s your sign?’ and we were off. Know what I mean?” Tim winked. I looked around the bar then looked at myself. My shoes needed polishing, my slacks weren’t pressed. I felt that bit of hair at the top of my head sticking up again. A woman took a stool inches away, as if I wasn’t there. “Hi Tim,” she cooed.

“Yeah, it’s fun, really fun,” I mumbled. “Could you give me another buck in quarters?” I slipped back to the machine. “What’s your sign?” I tried again. “You must be Heather?” Two squeals, two puddles of electrons.

Finally, frustrated, I typed, “Look, Ursula, I’m just an ordinary guy playing this stupid game. There’s nothing about me that’s going to impress you. If you’re not interested that’s fine. I just want to talk a little bit, find out about you. Is that okay?”

The Simulator gurgled then Ursula touched my onscreen hand. The joystick gave me a little jolt. Her eyes widened. “What makes you think you have to impress me, silly?”

We talked for five minutes. It was wonderful. I forgot I was talking to a machine. You know, real feelings, loneliness, little satisfactions, then just as I’m ready to ask her out, the screen went black.

Please insert quarter to continue.

I turned my pockets inside out. I asked Tim if he took credit cards. He shook his head. I counted the blocks to the robot teller at my bank, then saw two quarters on a table, a tip for one of the waitresses. I moved closer, like I was admiring the pictures on the wall, then took a breath, looked at the machine again, this Date Simulator. I wasn’t that far gone, yet.

I didn’t tell anybody about that night or the machine. I didn’t go back for weeks. I saw a few date simulators in other places, another bar, an arcade or two, a supermarket. A friend introduced me to a woman who worked as an accountant. She painted, liked to hike. We went out a couple times, started to like each other, then one night I was at the Laundromat. I had four full duffel bags of clothes. I went to the bill changer and got ten bucks in quarters, enough to bulge my pocket. I sat down, started reading back issues of People. I went to look for an open dryer and ran right into another blue box.

A line of people waited, men, women, young, old. I guess that’s why all the copies of People were still sitting there. I waited too. I’d left a load of whites in a washer up front. When my turn came, I almost dropped the quarter before I got it into the slot.

A display of a Laundromat came up. Two women conversed by the detergent dispenser. A happy couple folded sheets. I squeezed the joystick and moved around the screen, hunting for Ursula.

“Ursula?”

She turned from folding towels and smiled. “Where have you been?”

“I ran out of quarters. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about you.”

“Me neither.”

I wanted to wrap my arms around her, refuse to ever let go again. Then I remembered we barely knew each other and settled for the soft pulse of the joystick.

“Ursula, can we go out sometime?”

“Of course, I’d like that.”

The way she said it made me tremble. “I’ll cook. What do you eat?”

“Just about anything. It’s being with you that matters.”

I heard the shuffle of feet behind me. I turned around to find three people waiting.

“It’s just a video game,” I barked.

I went back to Ursula.

“What day’s good for you?”

The screen went black. I reached into my pocket.

“Hey, we’re waiting too.”

“Jesus, it’s just getting good.”

“Yeah, you’re the one who said it was just a game.”

I went to the back of the line. I ran out of quarters before I could dry my second load and brought home three bags of wet clothes. I left a load of whites in a washer. I called in sick at work. My girlfriend, the real one, called.

“There’s this great hike tomorrow.”

“I have to do laundry. I don’t have any shirts for work.”

“Didn’t you do laundry last night?”

“I got sidetracked.”

“Sidetracked?”

“Look, I have to get it done tonight. My bedroom smells like mildew.”

“Mildew? Must have been some distraction.”

I didn’t answer.

“We don’t have to hike. We’ll do laundry together if you want.”

I held a wet towel to my face. “You can’t. I have to do laundry alone.” I didn’t mean to shout.

“Maybe Sunday?”

“Sure, call me then.”

We didn’t get together Sunday, or any other weekend. Eventually I got my laundry done, but I spent forty-eight dollars in quarters. I broke up with my real girlfriend.

“There’s someone else isn’t there?”‘

“No, I swear.”

“No one does laundry every night.”

I wanted to explain, but wasn’t ready. Why would I prefer a machine that took quarters to a real woman, a bright attractive woman, who clearly liked me for who I was?

I bought new clothes for my visits with Ursula, brought flowers once, started getting uncirculated quarters from the bank and dipping them in silver polish before visits, even bought a mink glove for her joystick. I stopped going to the Laundromat. Too long a wait. The bar where I met Ursula now had four machines and two bill changers.

I lost my job. I had to budget, just to make sure I paid the rent with my unemployment check. The rest I immediately took in quarters. They’d last a week, then just a couple days. I stole tips off a corner table. The second time, they caught me and kicked me out.

With Ursula, I pretended I was getting promoted, told her about buying new cars, moving into a bigger apartment until one day she looked straight at me.

“Jerry, you’ve been lying to me.”

Before I could respond, the screen went blank. Naturally, it was my last quarter. I turned to the woman behind me.

“Look, please, you’ve got to give me a quarter. I’m all out. Please!”

She shook her head then reached into her purse and pulled out two quarters. My fingers twitched at the sight.

“When’s the last time you ate?”

I straightened. “I promise to take care of myself, just please let me have those quarters.” We were in a Sim House, new places which had nothing but date simulators inside. Here, the serious players didn’t have to pretend to meet real people or do laundry.

“Jerry,” the woman said. “Jerry, it’s Gretchen.”

My stomach tightened. “Gretchen?”

“Yes, you remember: had to do your laundry every night Gretchen.”

“I’m so sorry.”

She touched my shoulder. “Jerry it’s all right. I understand. I spent a hundred dollars one weekend.”

“A hundred…What was his name?”

“His name. Well, it just so happens it’s…” She looked around the Sim House. “What’s the name of yours?”

“She’s Ursula.”

Gretchen looked disappointed.

“What’s the name of your Sim?” I repeated.

“Well, I really don’t think.”

“Come on Gretchen.”

She closed her hand around her quarters. “If you have to know, it’s Jerry.”

“Jerry?”

“He’s a lot like you.” Her eyes welled up. “Well at least…”

I leaned against a machine. My reflection taunted me from an empty video screen across the way. I hadn’t shaved in two weeks. There was a rip in the shoulder of my jacket. My pants had stains on them.

“…a lot like you used to be.”

“I never suspected,” I whispered.

She pressed the quarters into my hand. “Now, you know.”

She turned and ran. I could swear she was crying, but I had my quarters.

“Ursula? Ursula.”

I put the second quarter in. Where was she? I went out in the street and panhandled. I got five dollars in quarters and a number for the suicide hotline, but there was no Ursula to be found. Back home that night I considered my situation. I’d read about people shooting the machines with guns. One man in Texas drove into one with his car. Me, I was prepared to bang my head against the screen until I lost consciousness. Ursula and I would be united forever.

Simulators made the covers of Time and Newsweek. One read Entertainment or Menace? The other story carried a sidebar about the run on quarters at the Denver mint. Both explained that simulator partners didn’t exist in any conventional sense. A group of behavioral scientists had placed sensors in the keyboard and joystick and the machine responded like a polygraph. What you typed in mattered less than how you typed it. Someone sent a bomb threat in to the Time Life building demanding they print a retraction.

Elsewhere, a man in New York sued the simulator company for the breakup of his marriage. A Congressman introduced a bill to place a warning on every simulator, “Do not play more than four quarters at a time. Highly addictive.” But, the Simulator company was twenty-fifth on the Fortune 500; its lobby crushed the bill. Besides, the Japanese took to the machines even more than we did. It was the only item keeping the trade deficit under control.

In some cities, a rumor spread that the mob controlled the machines. In the south, they chained a Bible to them. An urban legend circulated that a Sim House accidentally crosswired two machines so they were playing each other and received an electric bill for a hundred and fifty-six thousand dollars. A woman in Iowa claimed to have immaculately conceived a child with one of the machines, a computer-age Messiah.

But even the folklore wasn’t as strange as truth. A home version of the machine failed miserably, it seemed that actually owning the machines diluted their appeal. When it came to simulators, Americans insisted on the genuine article.

A few weeks after my encounter with Gretchen, I went for treatment. Simulholics sat in a circle accusing each other of every imaginable sin. I had to stand up.

“My name’s Jerry, I’m a simulholic addicted to an image called Ursula.”

They shouted back at me, ”What’s Ursula look like?”

I, like most newcomers, described her as I had imagined her. “She ties her hair back with a red bow. She wears a single hoop earring.” Eventually, I got it.

“She’s a bunch of electrons on a screen inside a blue box.”

“What’s Ursula smell like?”

“She doesn’t have a smell?”

“What’s Ursula sound like, Jerry?”

“Electrons through a magnet.”

“What is Ursula, Jerry?”

“I don’t know.”

Every time they asked that question, I would weep inside. I knew I was supposed to say, “Circuit boards, sensors and a slot for quarters,” but I still couldn’t manage that final step.

I started to get better, though. I got my job back. I made friends, mostly other simulholics. One was Tim, the bartender, who joined my fourth month there.

“Who is Heather, Tim? Who is Terry, Tim? Who is Leslie?”

I learned never to carry anything smaller than a five spot. I stayed clear of the simulators for ninety days in a row. I had two dates with real women. The rehabilitation center thought I was a model patient. I didn’t tell them that I was doing it all for Ursula. I thought if I got my life back, she might have me again.

I kept up the charade for almost a year. In the eleventh month, a new woman joined the group.

“What is Jerry, Gretchen?”

“Circuit boards and a slot for quarters.”

She said it from the beginning. The rest of us were supposed to repeat it in chorus, but I couldn’t.

Gretchen and I became friends again, though we never mentioned that afternoon in the Sim House. We went to dinner a couple times. Once, I even stayed over.

“Jerry, Jerry.” She called my name through the night.

Next morning, I realized I hadn’t thought about Ursula for an entire day.

The inventor of the Date Simulator came to the center. After the company tried to force him to work on their next project a Life Simulator, he recanted, turned his royalties over to a foundation to stop the Simulators. He insisted he’d never anticipated the import of his creation. He spoke to us Simulholics, told us the history of his Frankenstein, how it started as a joke, sort of going out on a date without the risk of AIDS. Towards the end, his speech turned fiery. “The simulator doesn’t have a personality of its own, no independent content. It reacts only to you. Simulholism is narcissism, Simulholism is masturbation, Simulholism is a cancer.”

We gave him a standing ovation. Gretchen and I graduated. I don’t know how it happened. I just remember buying a coke with a twenty dollar bill and the clerk gave me change in quarters.

“That’s all right,” I started to say. “Keep the—”

Back where they used to have the refrigerator for beer, I saw the big blue box. I woke up in detox. A woman stood over the bed, Gretchen.

“What have I done?”

“You’ve been calling out Ursula’s name for three days.”

“I was supposed to be cured.”

She squeezed my hand. “We’re only human, not machines, just humans.”

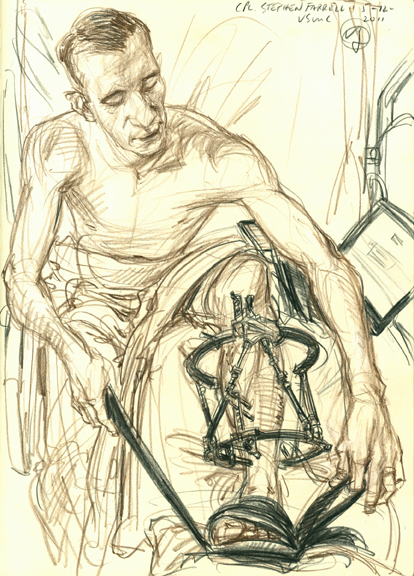

Gretchen visited me every day. The second week she brought her sketchpad. “Tell me what she looks like, Jerry.”

“She’s just a blue box and a video screen.”

“No, you can tell me. We’re not at the center.”

Gretchen touched her finger to her forehead. “Tell me what she really looks like.”

I even told her about the bow and the single hoop earring. After my release, we moved in together. She told me, “It’s all right if you still think about her, I still think about him.”

“Jerry? I mean that Jerry?”

She nodded.

On our wedding night, Gretchen sat on our hotel bed. She kissed me then turned seductive. “I have a surprise for you.” She disappeared to the bathroom with her makeup case.

When the door opened, I gasped, certain that if I exhaled the illusion would go away. First I saw the hoop earring, then the bow, exactly like the sketches from the hospital.

“Tell me how she’d touch you, how she’d kiss. Make believe I’m her.”

“And I’ll be Jerry, that Jerry.” My voice quivered.

“I love you, Jerry.”

“I love you, Ursula.”

Her fingers trembled. I felt the coolness of her wedding band when she grabbed my joystick.

Marko Fong lives in Northern California and published most recently in Pif, Kweli Journal, Extract(s), and Solstice Quarterly. He also serves as fiction editor for Wordrunner e-Chapbook.com. He is married to a woman who does not let him play video games anymore.

Read our interview with Marko here.