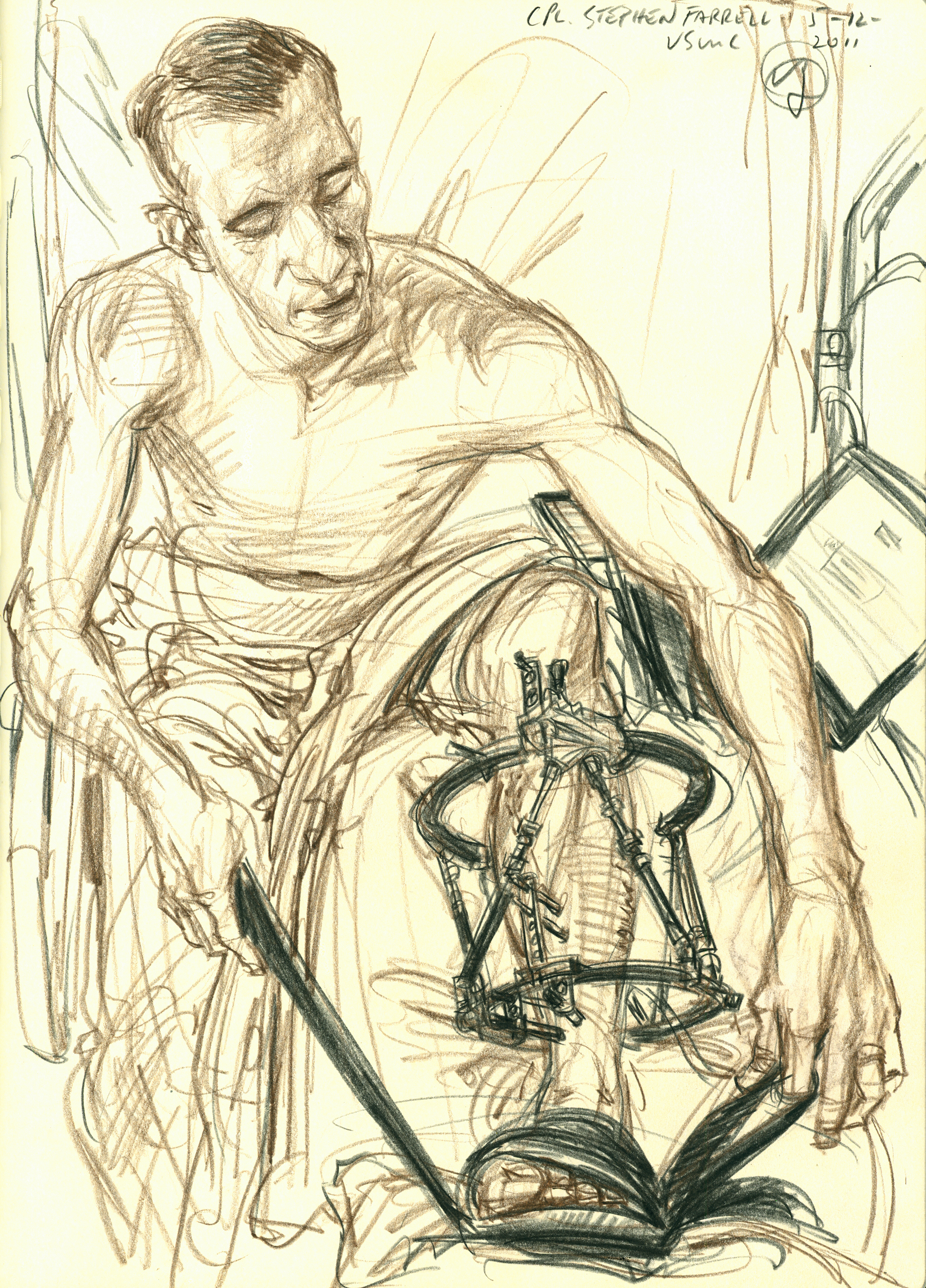

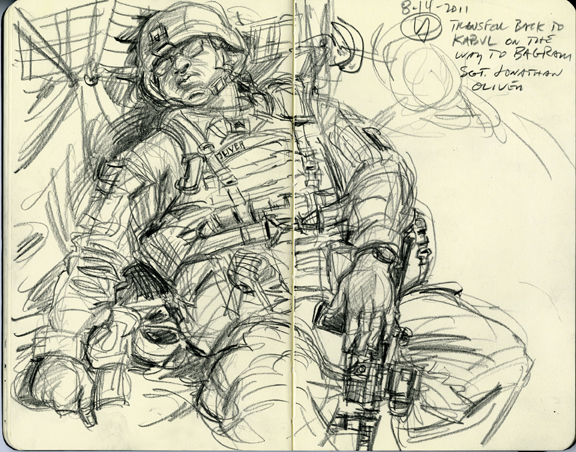

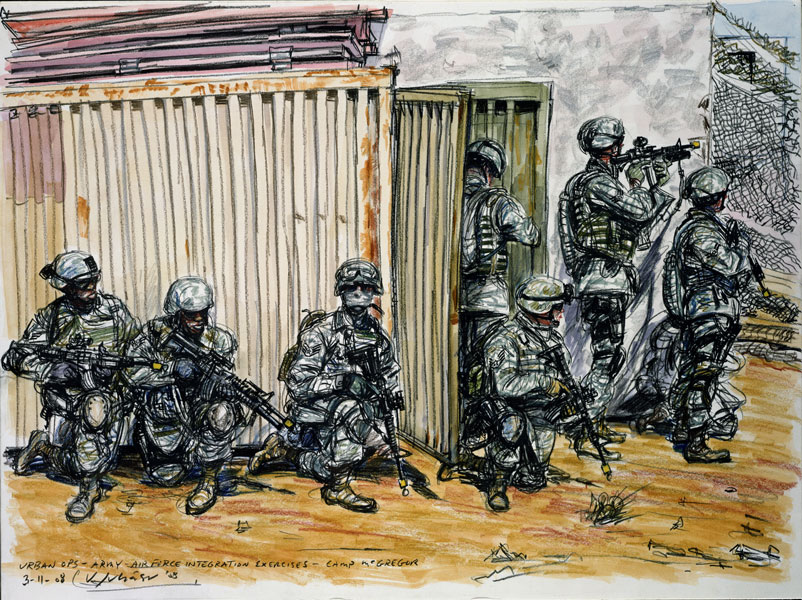

Image courtesy of Victor Juhasz, artist, first published through Sleeping Bear Press.

This ain’t a place miracles ever happen. This ain’t a place anything good ever happens.

Even the cops don’t like coming here, and they gotta come here, least once or twice a month. We get fist fights, knife fights, heads cracked by pool cues, shoulders broke by slamming chairs. Hell, two or three times a year there’s always some damn concerned citizen talking about shutting the whole place down on account a the drunks and drugs and fights and body bags that spill out into their nice clean world. But the clientele we get here, don’t nobody want ’em nowhere else, so we don’t never get closed down.

Tonight’s being quiet, all things considered, and I can tell some of the fellas are gettin’ antsy. We got all the regulars tonight. Knife and Chainsaw – don’t know as I know anybody’s real name – are at the pool table, with Godzilla holding up the corner, waiting his turn. Mercy (’cause he’s got none) and Harley are playing cut-throat poker. Crank’s sharpening darts on his boot and Shirl is at the table closest to the door, being available to her own brand of clientele as they come and go, and the rest of God’s Forgottens are taking up space across the barroom floor, smoking and drinking and doing things their Mamas wouldn’t approve of.

It’s gettin’ late and just as I’m thinking this night might end and no blood on the floor, in walks Soccer Dad. Young guy, thirty if that. Clean hair, trimmed nails, clothes that seen an actual washer and dryer. He’s so far outta where he oughtta be, he might as well be on a different planet. Half the place turns to look at him, like wolves who suddenly notice supper. I’m feeling generous – and I don’t want the cops back less’n three days after the last go-round – so I go over to tell him that if he don’t want to be tomorrow’s ‘identity withheld’ he better turn tail and run.

Especially since he’s headed right towards Godzilla.

I don’t know Godzilla’s right name, and that ain’t even a name he give himself. I call him that – not to his face – ’cause he’s huge and seems near always in a bad mood. Right from when he first set his butt on my barstool, it was like he rolled in off the thunderclouds what was hanging over the street that night, and the dry lightning flashing red to blue, cloud to cloud and back again, like it was Heaven and Hell playing keep away with the thunderbolts.

I took him for military, Godzilla, right from the jump. It was his boots that looked it, sure, but it was more than that, too. Something hard to describe, but something – or a lot of somethings – one old soldier recognizes in another. Not that Godzilla’s anywhere near to the years I got collecting behind me. Not on the outside. On the outside, couldn’t be he was any more’n twenty-five. On the inside though, I could tell he was old. Same as everybody else ever set up shop in my place, Godzilla was seen too much, done too much, lived too much, old.

Being fair, he’s got niceness in him. Might be he’s bad tempered most of a day, but he’s never mean to somebody isn’t mean first. A person nice to him gets nice given back, sometimes outta two hands. One time he asked was I okay after the old woman laid me open with a beer bottle. For a whole coupla nights after that he did any heavy lifting it was I needed around the place n’wouldn’t even take a drink on the house for it. Shirl sure done got her a special place for him, even with her being old enough to be his Mama, or even his grandmama. Godzilla holds her chair and her coat and the door whenever it is she needs it, and it ain’t that I think he ever bought himself any of what it is she sells, but if it ever was he did, I’m thinking it’d be his for the asking.

But those that mess with him get messed back. He don’t like being crossed, he don’t like being touched, hell, sometimes he don’t hardly like being talked to. Since he’s been coming here all this past summer, he’s broke two arms, three noses, and six fingers. Other people’s. That I know of. Don’t get me wrong – they all had it coming. Just didn’t none of ’em see it coming. Nobody, not even Mercy, messes with Godzilla.

And Soccer Dad is headed right for him.

“Hey Buddy -” I try. I put my hand on his shoulder, meaning he should leave while it’s still in its socket, but he throws me off and keeps walking.

‘Your funeral.‘ I think and follow close for ringside seats.

Godzilla’s paying nobody no mind but the pool game. Soccer Dad grabs his arm and pulls him around and Godzilla comes up swinging and I’m thinking the game is on. Soccer Dad don’t even flinch – he don’t care, he stands there glaring at Godzilla, and Godzilla’s car-sized fist stops dead just before it wallops him.

“What the hell?“ Soccer Dad demands and Godzilla’s face does something I ain’t ever seen it do – it goes soft, like that day Eyeball found his Mama’s wedding ring he thought he lost for a week, jammed up under a loose board under the pool table. Godzilla goes soft and looking like he don’t know what to do and drops his hand and don’t even try to look Soccer Dad in the face.

Mercy ain’t having none of it though. Tonight’s been quiet and he don’t like quiet and could be he’s taking Godzilla’s idleness personal. He shoves Soccer Dad but no more’n asks, “Who’re YOU?” before he’s on his face with Godzilla’s foot in his armpit and his arm twisted back around the wrong way and Godzilla saying, “He’s somebody you walk away from. Understand?“

And it ain’t until Mercy snivels ‘Yessir’ practically that Godzilla lets go and goes back to stand in front of Soccer Dad, looking soft and worried and like he got caught after curfew. By now they got the attention of the whole barroom, only neither of them don’t notice or don’t care. Soccer Dad don’t say nothing, he only just keeps glaring, like he can burn an answer outta Godzilla. It was then I seen the resemblance. Soccer Dad don’t have more’n a couple-three years on Godzilla, near to as tall, that same dead-on stare I seen Godzilla blasting folks with, and it’s on me to figure Soccer Dad is Godzilla’s brother.

“Tell me you got amnesia.” Soccer Dad snarls at him, like Godzilla ain’t got inches and attitude on him and it comes on me that Soccer Dad is only what he shows to the outside. There’s death under the clean clothes and trimmed nails, I can tell. “Tell me amnesia is why you’ve been back five months and didn’t even let us you were alive.”

Godzilla’s throat is bobbing like he can’t swallow something and he won’t look at Soccer Dad and his head tilts like he’s trying out excuses in his brain until finally I guess he finds one that might pass muster.

“Up ’til now, I didn’t know I was alive.”

Whatever that means, it means more than anything to Soccer Dad ‘cause he gets a look as soft as Godzilla’s. He wants to say something, he wants to say a lot of somethings, but he ain’t gonna say ’em here.

“Let’s go.“

He turns like that, like his word is law and I guess it is, ‘cause Godzilla follows him. He even puts some hurry into it like Soccer Dad might just go on and leave him behind, never mind what he just went through to get him.

I follow ’em to the door and a little beyond, ’cause I know this ain’t something I’ll ever see again.

Godzilla follows Soccer Dad to the curb where they need to cross and Soccer Dad puts the back of his hand on Godzilla’s chest, saying with no words to mind the traffic. And Godzilla, who I know can crack glass just by looking at it, smiles.

The whole barroom is quiet, hushed like we all just maybe witnessed a miracle, and I don’t know, I think maybe we did…’cause one of God’s Forgottens got remembered after all.

Maureen Lougen started writing in fourth grade. When other kids were actually doing their schoolwork, she would pen a juvenile blend of her favorite TV shows on scraps of paper instead of paying attention to the teacher. She lives in a little town that’s seen better days, about a quarter mile from Lake Ontario. During the summer, the town smells like dead fish. (Which might explain why she’s still not married.) She shares her aged house with her too-smart-for-his-own-good son, a beagle that needs a C-Pap machine, a beagle-basset that suffers from Seasonal Affective Disorder, and two cats that hate each other. An avowed busybody and Nosy Parker, Maureen steals her ideas from other people’s lives and plunks them down in the middle of her stories just as they are. It’s just easier than doing research.