Susan Rogers: You and I have both written several poems together with a group of poets organized by Kathabela Wilson called POETS ON SITE. One focus of this group is writing poetry inspired by the artwork in local galleries and museums and then performing these poems in the location of the artwork. These ekphrastic poems are always an interesting collaboration with the poet and the artist and are part of a long tradition of poets engaging artwork. Sometimes ekphrastic poems are narratives about the artists who created the artwork. Sometimes ekphrastic poems are interpretations of the story that seems to be held within the artwork. I really love your poem “Still Life with Bird” that you wrote for Susan Dobay’s painting “Still Life With Bird.” This poem will be published soon in the POETS ON SITE collection, “On Awakening.” In this poem you manage to engage both visual art and music, spinning a riff on Charlie Parker. The poem is written in a very fluid, jazzy style that resonates both with the painting and with Parker. What was the process you used to engage Susan Dobay’s painting and write that poem?

Millicent Accardi: I looked at the painting and tried to see what it was telling me and, from the table and the feeling of falling from the perspective as well as the title. It reminded me of the music and the life of Charlie Parker. So I went with that, like I “go with” a jazz piece. From that premise, I tried to build an adlib solo impromptu response to both the painting and the music and how they tied into each other.

SR: You have created a wonderful forum for poets to get together and workshop their poetry: The Westside Women Writers. This group both encourages the creation of new poetry and facilitates the process of revision, in that it provides constructive feedback to the poets on their poems. In addition to bringing your poems to this group, what else do you do to craft your poems? Do you have any personal guidelines you follow in revising your work and how do you decide whether a poem you have written is “finished” and ready for publication?

MA: I write in purple notebooks; I write on the computer; I write in my mind, in the shower, while driving. It depends. Poems beget more poems and I find when I am “on a roll,” the poems come easily and frequently. When I am not, they are non-existent and I do not press myself to produce work. There are times when I set the stage for poetry to “be possible,” like when I participate in poetry prompt exercises. One that is sponsored by Molly Fisk has been of particular use to me. She posts one prompt per day and a group of writers write to that prompt every day for a month. Early in 2011, I did 3 or 4 solid months of these prompts. Then, I felt I needed a break. And my day job called out to me to get to work to earn money for the mortgage and taxes. Writing is like that for me, either feast or famine!

As far as completion, sometimes I feel as if a poem is never finished, but, for me, it is usually one of two things: either I have nothing left to add or take away to make it better and I give up and surrender that it is complete, OR what I have written matches what I have in my mind. When it matches, then my job, for whatever it is worth, is finished. Done. Otherwise, every poem I have ever written is open to change, open and available for revision. Even after a poem has been in print.

Here’s a quote that comes to mind, “Some poems are very hard to write, must be carved into granite with a feather. Others burst out of the head armored and ready to command a chariot drawn by swans.” –Dean Young

SR: Which three poets would you say have had the most influence on your poetry and why?

MA: I think I will go with contemporary poets first: citing Lynda Hull, Ralph Angel, Pablo Neruda, WS Merwin, William Stafford, CK Williams, ai, Michael S Harper, CD Wright, Ruth Stone, and a wonderful Portuguese poet, Nuno Júdice. From other times: Yeats, TS Eliot, and Christina Rossetti. In particular I appreciate and am amazed by poets who transport me to new worlds, new places either inside their heads or in a literary landscape.

SR: Imagine you are sitting in a coffee shop in a city where you do not know anyone. You are quietly reading a book of poetry and you overhear a conversation at the next table between two people. They are talking about poetry and you hear them mention your name and one of your books of poems. It could be “Injuring Eternity,” “Woman on a Shaky Bridge,” or your soon to be published book, “Only More So.” Or it could be the unwritten book you will publish after that one. They say something very complimentary about this book of poems. What would you most like to hear them say about your poetry? What would you consider to be the highest praise for a poet?

MA: My answer is very simple; that they are reading the work. This is all a writer can ask, except perhaps that the work affects them in some way, either by actions in their life or causing them to sit and stare into space for a moment to think, to ponder, to see the world or their lives in a new way.

I am continually astonished when I “meet” someone in cyberspace who has read my work. The other day, Carlo Matos, a poet in Chicago, posted a line from one of my poems “Spitting Nails” as his Facebook Status. Now, THAT made my day!

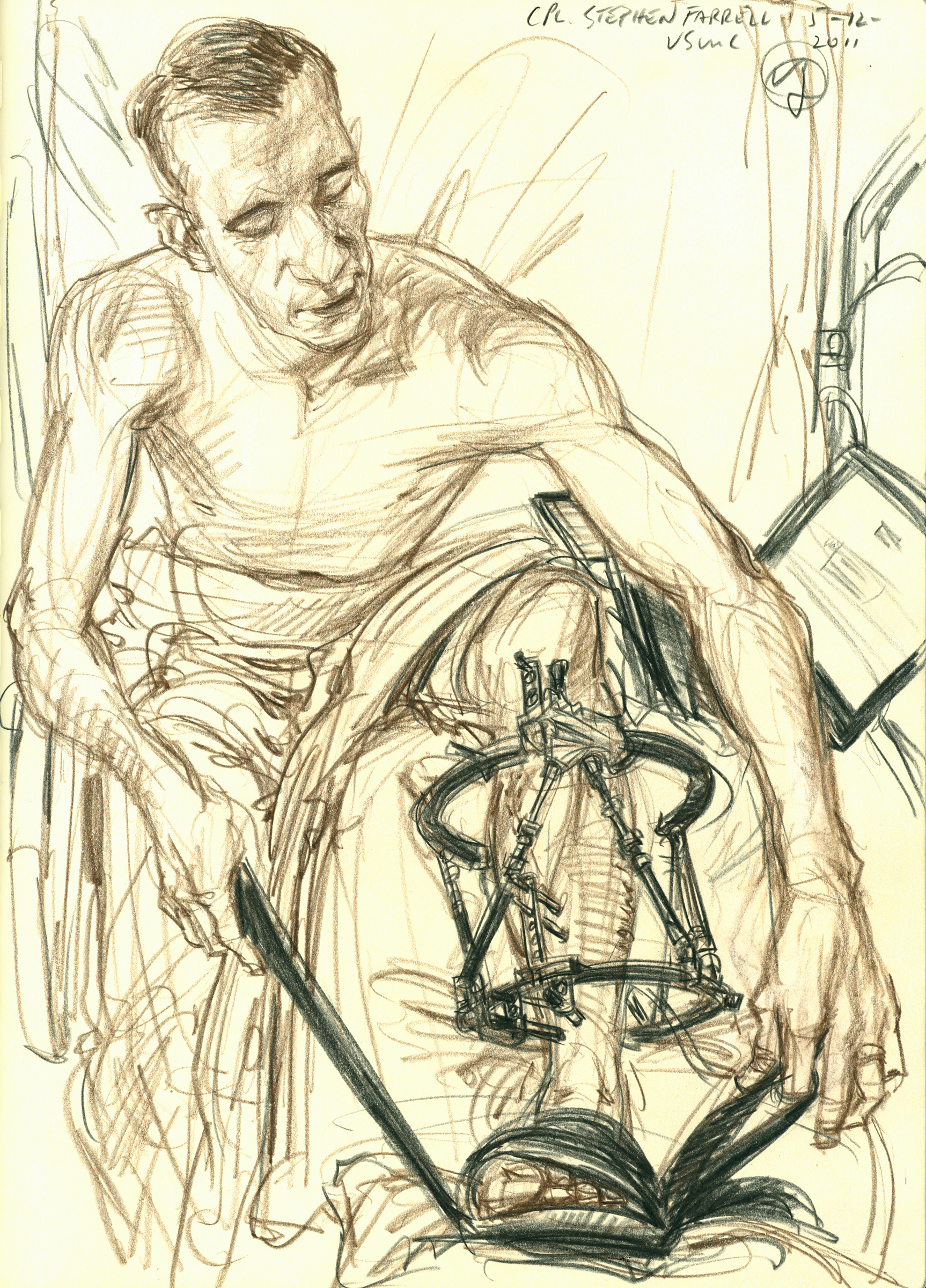

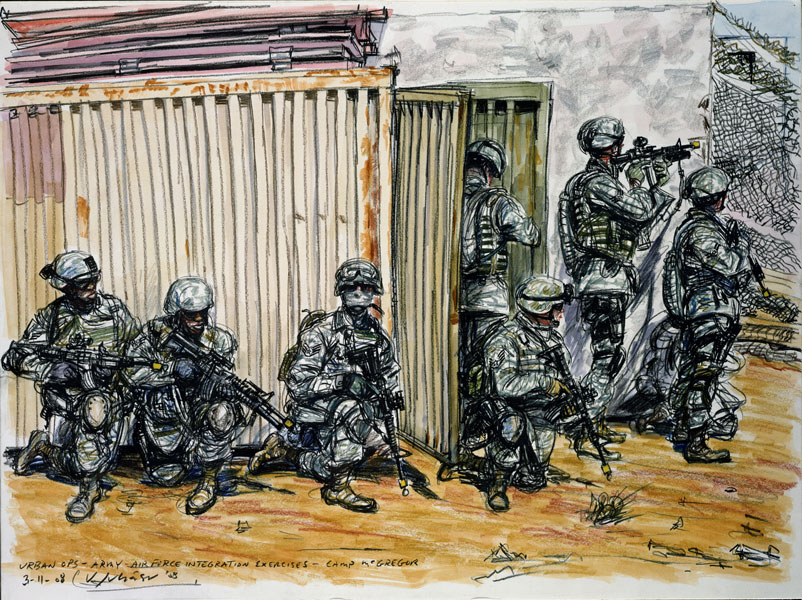

SR: On September 24th 2011 you participated along with your Westside Women Writers group in a 100 Thousand Poets for Change event. This event was a global initiative to use poetry as a vehicle to promote peace as well as positive social, environmental and political change. The Westside Women Writers wrote poems about peace and recited them on that day. Then afterwards you posted the poems the group had written online as part of this global event. The poem that you included in this event, “Renovation” is a beautifully written and very poignant contribution describing a veteran’s painful journey to reconstruct his life. I felt it was a very apt choice for this purpose as it eloquently speaks to the lingering pain and the wounds that never heal inflicted by war and thus speaks to the importance of maintaining peace in the world. Is this role of poetry as a force for change in the world important to you?

MA: “Renovation” was originally written as a piece about a man who had lived through a way (I was thinking of the Vietnam War) and who had returned home to mundane chores and a daily life that, while it felt familiar and safe, was also seen through new eyes, that everything was or had been transformed because it was now seen through a new veil, a veil of war and having served overseas and having seen horrific things and that he was not or no longer capable of existing as the same person he was before; incapable of putting in tile or a floor or even hugging his wife. There was this wall of separation. He’s been to a place of pain that he could not talk about or express and it clouded every aspect of his daily life. And he could do nothing and felt helpless to change it.

As a teacher a community college I had many students in my night classes who had returned from the Middle East, who had served in the Army or the Marines and were back home, many of them with young families and new marriages and they were making their way as grocery checkers or working in gun factories or making deliveries. They were plodding along, trying to do the right thing, but in their minds they were back in the sand, nervous, alone, in a place of killing that no amount of normal life back home could erase. I saw many of them end up in jail for odd reasons, drunk driving, abuse, petty thieving. They did not know or understand how to “be” normal as they were.

SR: Just as there are many different forms and types of poetry there are also many different reasons for both writing and reading poetry. Poems can be inspiring, informative, transformational and even therapeutic. Reading poetry can help us recover a part of ourselves that we have lost and writing poetry can help us process and recover what we once knew but has been buried deep within. In what way has poetry been an action of “recovery” for you? In what way do you hope it will serve as a sense of “recovery” for your readers?

MA: Recovery, to me is recovering one’s life. Plain and simple. It is getting back or unearthing what a soul should be, before whatever happened that took away livelihood and free will. Recovery may be recovering from drugs or alcohol or grief. It could be recovering from a sickness? It could be a healing from a place of artificiality to a place of real. Recovery is a process of peeling back the layers to get to “self.” To return to or to find for the first time the person you were or were or are meant to be. To be not in recovery is to deny life, to cover life up and bear false witness to your own being.

SUSAN ROGERS considers poetry a vehicle for light and a tool for the exchange of positive energy. She is a practitioner of Sukyo Mahikari— a spiritual practice that promotes positive thoughts, words and action. She is also a photographer and a licensed attorney. Her work can be found in the book Chopin and Cherries, numerous journals, anthologies and chapbooks including the forthcoming San Diego Annual: The Best Poems of San Diego 2011-2012. In 2011, her comments about poetry and poetry workshops were published in an essay on the national site, Women’s Voices for Change. Her poetry can be heard online or in person as part of two audio tours for the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, California. She has also been interviewed by Lois P. Jones for KPFK’s Poets Café. This interview is archived at http://www.timothy-green.org/blog/susanrogers/.·