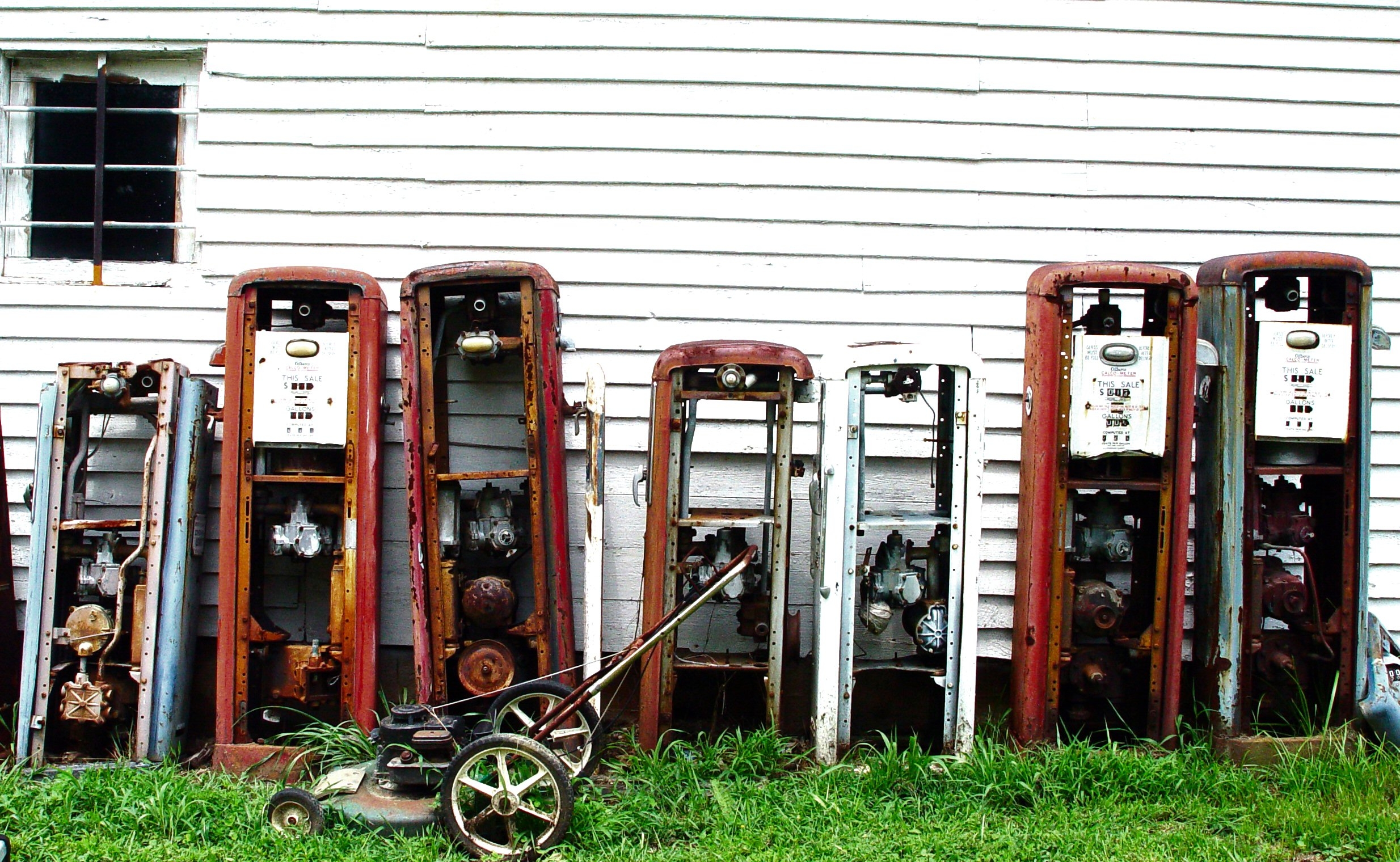

Image by Jenn Rhubright

A month before my grandfather committed suicide, I drove him to Russ’ Auto Repair in Canton, Ohio, for his Cadillac to be fitted with a left-foot accelerator.

He couldn’t use his right leg because of a recent hip replacement. A prosthesis was installed to help support the weight of his body, which at 280 was the lightest he had been in a decade. Losing weight was one of the three criteria he had to meet before the operation—along with quitting smoking and drinking—and though he was normally defiant of physicians, this time he had followed doctor’s orders. After watching my grandma slowly die in a hospital room earlier that year, he had made a commitment to stay mobile. He wanted to be able to take care of himself, so he wouldn’t have to move in with anyone, or—his greatest fear—into a nursing home.

My grandfather had planned to be at the auto shop as soon as it opened at nine, so I arrived at his house at 7:50, hoping to be on the road by eight. When I arrived, he was already sitting in the car, and his walker, collapsed on the driveway, lay near the passenger side door. As I approached the car, he rolled down the window, and said, “I’ve been waiting here all morning. Now, close my back door.”

My grandfather had always been an impatient man. Throughout my life, if my grandmother and he were at a family function, he would abruptly stand up at the most inappropriate time, tell my grandmother to get her things, and walk to his car. The grandchildren would have to run to the car and wave as he backed out of the driveway. Once I asked my mother why grandpa always left so fast. She shrugged and said, “I guess when he decides to go, there’s nothing you can do to stop him.”

I caught a glimpse of the wreckage in the house as I reached to close the door. The house, which had been kept immaculate by my grandmother, was lost under dirt and clutter. Stacks of dirty dishes sat in the sink, two dining room chairs leaned against the wall, and magazines, letters, and empty glasses covered the dining room table. In the brown, plush carpet, the feet of the walker left small circular indentations that marked my grandfather’s journey from the living room, through the dining room and kitchen and to the car. Between the walker’s tracks, the carpet was raised like an acrylic wake, a wake left by a dragging leg that still hadn’t adjusted to the artificial hip’s metal ball-and-stem that had been inserted three weeks earlier. As I closed the door, I considered that it probably had taken him much of the morning to shuffle to the back door.

I returned to the car, put his walker in the trunk, opened the driver’s side door and slid behind the wheel.

“Took you long enough,” he said. I could smell mint on his breath, a sure sign he was drinking again. He offered me a cigarette. Since I didn’t have enough nerve to tell him he shouldn’t be smoking, I decided to lead by example. I declined. “Then, what are you waiting for?” he asked. “Let’s go.”

During the first miles of the drive, my grandfather began his critique. He told me when I was going too slow, too fast, and when I didn’t come to a complete stop at stop signs. When he asked questions, they always had two parts. The first part was, “What’s the matter with you?”

The ride became a litany of: “What’s the matter with you? Don’t you know how to drive?” or “What’s the matter with you? Don’t you know how to use a turn signal?” or “What’s the matter with you? Why did it take two weeks to return my phone call?”

I had been avoiding his phone calls because I couldn’t deal with how depressed and reserved he had become after my grandmother died. I lived forty minutes away so it was easy to avoid his calls or, more precisely, him. So I let the rest of my family deal with him. I kept my distance after his first suicide attempt, because I didn’t know what to say to him. My mother finally made me contact him. She told me he needed the accelerator fixed and I was the only one available to drive him. If I would have known it would be my last trip with him, maybe I would have been more enthusiastic instead of focused on not wanting to deal with an old, depressed man for an entire day.

I indulged my grandfather’s orneriness because he seemed to be the grandfather I remembered. The one who decided it was his job to point out any and all flaws. I thought he had turned a corner and was getting better. I considered that maybe the new hip, the alcohol, or the freedom that would come with the accelerator was beginning to bring him out of his depression. I began to feel comfortable around him again, so when we were near Canton, I played along. I told him that he was getting too old to know what he was talking about, and it was best if he just shut up, or, as I said, “Shaddup!” We laughed together, and I continued trying to show that he was wrong to critique my driving. In fact, I became so caught up in proving that I knew where I was going and what I was doing that I missed the exit signs, becoming temporarily lost.

After forty-five minutes at Russ’, the left-foot accelerator was installed: a pedal placed on the left side of the brake and a bar and lever extending to the gas pedal on the right. I drove through Canton, and the car lunged and stopped repeatedly as I tried to find the right amount of pressure with my left foot. Because I wasn’t sure of the exact location of the pedal, sometimes I would hit the break instead of the gas, sending us into our seatbelts. Each time this happened my grandfather said, “Wrong one.”

The most frustrating aspect of the apparatus was that it made me aware that I was driving. That awareness made something so simple, incredibly difficult. Even now, I wonder if that is how my grandfather had felt. Everything became slightly more difficult after my grandmother died: cleaning the house, making dinner, walking, and, until that moment, driving. Perhaps the frustration I had in the car with that damn left-foot accelerator represented a small amount of the frustration my grandfather felt every day with everything he attempted to do.

Outside Canton’s city limits, my grandfather told me that my driving was making him sick, and it was his turn to show me how it was done. I stopped in a supermarket’s parking lot, so we could switch. In no time at all, my grandfather mastered the accelerator.

“What’s the matter with you?” he asked. “The damn thing’s easy.”

A mile away from his house, I had the sensation of moving sideways. The white line marking the road’s shoulder slipped under the car. The tires kicked gravel and dirt as the car approached a drainage ditch. My grandfather was asleep with one hand on the wheel and his head on his shoulder. A month later, a neighbor would see the walker and my grandfather slumped against the house, his legs buckled under him, and his head, once again, on his shoulder. Thinking that he’d fallen, the neighbor would run to help only to discover the semi-automatic pistol and the half-inch entry wound above his right ear.

“Hey,” I said. My grandfather woke and swerved the car onto the road. “What’s the matter with you?” I asked.

I expected to see his half smile, the one that indicated an insult was coming, but he didn’t smile or have a comeback. He hadn’t even looked at me. He kept his eyes on the road ahead of him, and I watched his cheek twitch as he clenched and unclenched his jaw. I thought about asking him again if something was wrong, but I never had a chance because he pushed the accelerator to the floorboard and turned the corner too quickly. Instead of talking I had to find a way to brace myself.

Brian Hall is an Assistant Professor of English at Cuyahoga Community College in Cleveland, OH. His essays and photographs have appeared in a variety of journals including The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Palo Alto Review, Exquisite Corpse, The Lullwater Review, and The G.W. Review.