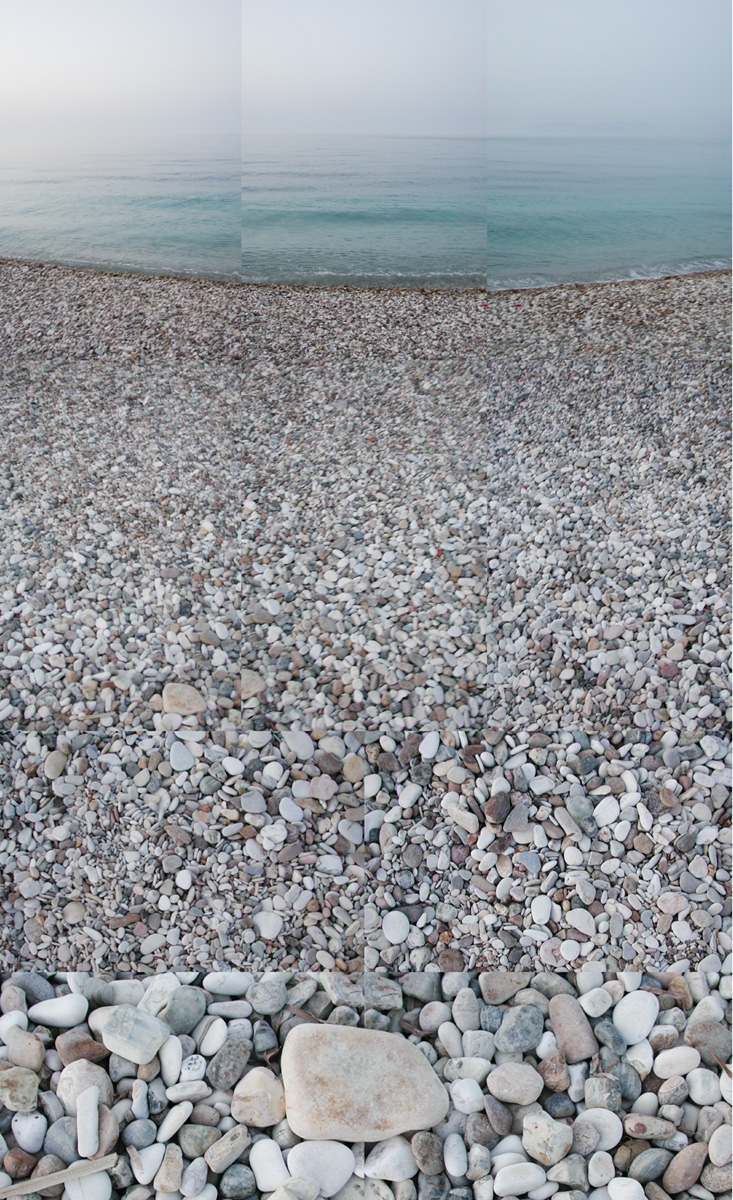

Beach at Scopello, Sicily by Matthew Chase-Daniel, 2000

I signed up for a yoga class for writers because I needed to focus.

I’d successfully written a novel; it was even published. But for the past year or so, I’d been unable to concentrate. During the first class in the series, which was about sound, Lisa, the instructor, rang a bell and we listened until the walls soaked up the ringing. We ohm-ed three times as a group, and the room vibrated with sound. We could feel it against our skin. We stretched and repeated the sun salutation; our bodies morphed into snakes, cats, dogs, and children.

For our first writing exercise, we sat in pretzel legs as my kids say. Our backs were straight; our hands palms up on our knees, thumbs and index fingers touching. Lisa instructed us on how to breathe. Inhale and fill the belly, exhale and bring the bellybutton toward the spine. I focused, in and out. How difficult could it be? But of course my breath was choppy. My belly expanded as I exhaled. I tried again. Perhaps Lisa saw the frustration on my face. She said, “Breathe without judgment, but with compassion.” I’d been breathing all my life, so I must have had some idea how to do it. I just lacked any grace in the matter. I persisted and tried to look upon myself with compassion.

We stayed seated, breathing and listening as Lisa put on John Coltrane’s “In a Sentimental Mood.” I’ve always loved Coltrane, but hadn’t listened to him in a while. I sat breathing, breathing, and then, crying. I bit my tongue and tried to keep my jaw from quivering. A tear escaped and I wiped it away, then another. I was no longer focusing on breathing, but on not crying. While I loved the music; I didn’t have an emotional connection to it. I wasn’t listening to it at the birth of either of my children, it wasn’t playing at my wedding, and I didn’t immerse myself in Coltrane following a rough breakup long ago. So why was I crying?

After a few minutes, Lisa asked us to write about the music, or about the other sounds we’d experienced in class. My first sentence was, “What the hell was that about?” I kept writing. Writing was why I had come. I needed to get back to it. For the past year and a half or so, I’d been unable to concentrate. I’d become a caregiver, not only for my children, but for my husband who at forty was diagnosed with cancer, and then later his mother, whose lymphoma had returned. Caregiver is too strong a word; it makes it sound like I did more than I did. But after all that had happened, I was emotionally bankrupt. I was empty.

Why Coltrane? I wrote. Why tears? Perhaps Coltrane was speaking to me; he understood about the past and about what was lost. I realized that it wasn’t the music alone that made me cry. It was the breathing. It was me breathing. Me, after all that had happened, catching my breath.

The class ran late, so when I arrived home our company was already there. The couple sat at the kitchen table with my husband. The children were playing upstairs.

“We’re swapping cancer stories,” my husband said.

I sat in my yoga pants with a glass of wine. Our company was a couple we’d met through friends and had seen a few times. The reason I like them is that they are unapologetic about really loving each other. The wife had thyroid cancer a few years back. Her torture was hormonal more than surgical, months of treatment, then finding the right balance of medicine so she could return to stability, to her family and life.

My husband had chemo and radiation, and four surgeries in the past year and a half. Sitting at the kitchen table, Peter was only up to recounting his second surgery, the one that was supposed to be a “procedure” followed by a few days in the hospital. Then we were to join our children down the shore. Two days after the surgery it was apparent something was wrong. My husband was a grayish green, panting and sweating, barely able to walk 100 feet. The day before he’d lapped the hospital floor fifty times. As he talked, I pulled myself into a ball on my chair and felt acid rise to my throat. I wanted my husband to tell his story. And I really didn’t.

It is all too raw for me and I find myself back in the hospital recliner, wedged between his bed and the windows, the overcast day showing on his face. Peter is asking me to stay overnight. He’s afraid and I act like I’m not. I watch him barely sleeping. He’s been the perfect patient. Everything up to this point has gone as planned. This procedure was to be the end of a yearlong ordeal. But it isn’t. He’s dying, I think, and I can’t do anything. I walk the hall and ask the resident to check him again and again. They take him into emergency surgery the next day; he’s in septic shock, then he’s in the ICU. Twelve days all told and we don’t meet our children down the shore.

In graduate school, I frequently got into discussions with my fellow fiction-writing friends about whether to write autobiographical stories. I was adamantly against it, for me. My argument was that I needed more time to process what had happened in my life, possibly for a decade or two, before I could incorporate it into fiction. Meanwhile they seemed to be able to write the story as the door closed behind their lovers or the ambulance pulled away.

Joan Didion says she writes to know what she’s thinking. After listening to Lisa, and my breathing, and to Coltrane, sitting at my kitchen table, I thought maybe I don’t need to process before I write, maybe I need to write in order to process. It won’t be fiction, at least not at first. I may never share it. But I need to write to know what I’m feeling, and maybe to let go of all that was lost.

Listening to great jazz is like listening to conversations. Sometimes it’s an argument, sometimes wooing, sometimes goodbye. That afternoon, Coltrane was whispering to me: tell me. Tell me everything. And in the quiet of my own messed up breathing, I heard him.

Susan Barr-Toman is the author of the novel When Love Was Clean Underwear, winner of the 2007 Many Voices Project. She was born and raised in Philadelphia where she still lives with her husband and two children and where she teaches creative writing at Temple University and Rosemont College. She holds an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars. Visit Susan at www.susanbarrtoman.com.

Read an interview with Susan here.

Pingback: Catching My Breath – Susan Barr-Toman