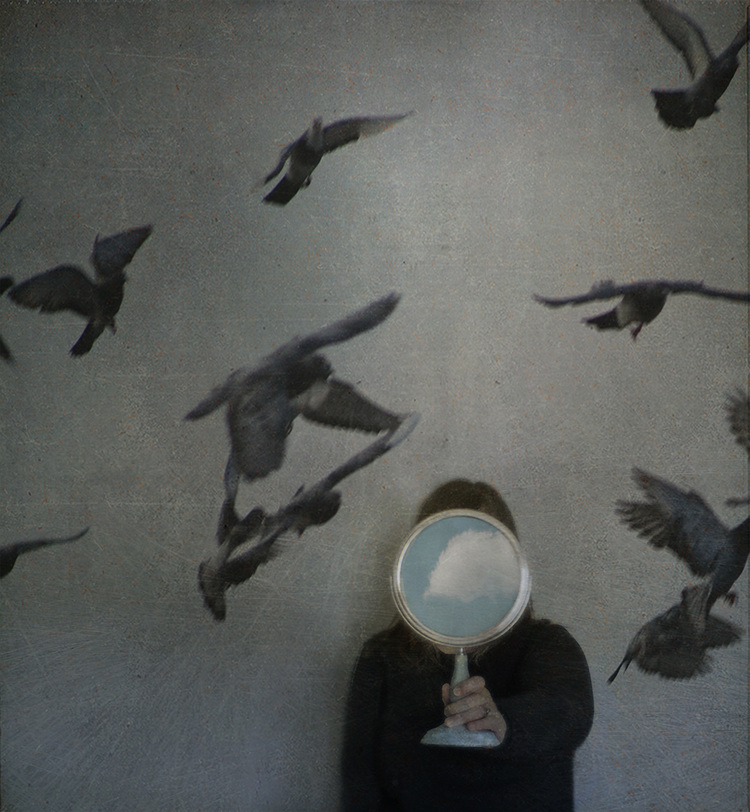

“The Mask of Comedy,” Photograph by Fay Henexson

Tessa ~

I was sixteen when I realized my dad was cheating on my mom. I was the only one who noticed. I had to tell her. For years after, they were in counseling and my mom was trying so hard, while my dad was just lying, deceiving, and deteriorating.

And then he started making the sketchiest career choices. Like starting his own cell phone business in the middle of the recession when he knew nothing about business or cell phones. Then he tried selling cars. Then he couldn’t hold down a job at all.

They got divorced. For so long my mom hated him. She treated him horribly. I mean, I hated him, too. I treated him horribly. We just didn’t realize. We didn’t understand that the first sign of dementia isn’t trouble remembering. It’s behavioral changes. People with Frontal Temporal Dementia lose any kind of empathy. They can’t read anyone else’s feelings. But he was only fifty. And it’s so hard to diagnose it early on.

I didn’t even notice the physical symptoms until ten years later. It started in his arms.

Carrie ~

My father had six children: me, another girl with my mom, and four more with his wife after her.

Not one of them helped when my dad got sick. It was a full-time job. I used to spend so much time at Maryhaven—the nursing home my dad was in—and the patients all loved me cause I’d come in singing My Fair Lady at the top of my lungs. I used to do improv, see. I used to do Comedy Sportz, so I’d really put on a show. Then I got into organizing ice-cream socials and music therapy—oh, and animal therapy, everyone loves playing with puppies. And I’d connect with the patients’ families—I knew what they were going through—so when a position opened at Mather Pavillion, I took it. I was basically doing the same things I’d already done at Maryhaven, but this time for pay. Except I haven’t been able to work since I broke my kneecap. I’m on my feet the entire time at work. Thank God my insurance covers me while I’m on crutches, cause I literally can’t do anything there sitting down.

Amber ~

So I’m the oldest of six, and I’m thirty. Andrew, my middle brother with Down syndrome, is twenty-three. It’s kind of a joke that two months after I got married, my mom asked when I was going to start having kids. I told her, “I spent my childhood raising your kids and I’m still looking after Andrew.”

Every summer I took care of my younger brothers. When I went looking for a real job, everyone asked, “Any previous job experience?” Um, none, technically.

So instead of kids, I have a lot of pets: two dogs, four cats, two chipmunks, a ball python, and a fennec fox. And Andrew’s the only one in the family besides me who knows all their names.

My husband, Gus, is really good about it all. His parents died when he was two and his grandma raised him. We met in high school, so he knew my story. My mom got custody of the younger boys at first, but when she moved to Vermont my dad fought for Andrew and won. Dad has nine siblings here in Milwaukee and Andrew’s very close with his grandma. But Grandma can’t really do much now and my father’s a vascular surgeon, so he’s always on call. Gus and I take Andrew every other weekend to help out. His favorite thing is pasta. Gus makes it every night he’s here.

Tammy ~

I would have Andrew out here in Vermont with me if I’d had my way. But I didn’t have an extra $60,000 a year. So, he’s there in Milwaukee. I tried making Amber his legal guardian, but my ex-husband and I do a lot of fighting so he’s the legal guardian. It should be Amber cause she actually makes the decisions. The group home calls her cause they’ve learned that her dad never answers his phone. He’s kinda not real responsible.

I told Amber I don’t want Andrew living with her cause it’s too much for anybody. She’s always wanted to move to Portland, so if she does she’ll probably bring him with her. She’s been closer to him than any of the other kids. She’s the oldest. She really goes out of her way. She’s the one I count on.

Naomi ~

When I was younger, I worked at a camp for kids with special needs. My brother called them, the Tards. He’d say such horrible things and make me cry. Like, “Why do you want to work with kids who only have half a brain?”

Years later, Caroline was born. She had the lowest muscle tone the physical therapist had ever seen, like a ragdoll. But she was a happy baby, really delightful, and my brother adored her. Then she started missing milestones. Sitting up, scooting, and each one she missed was another blow. We waited four years for a diagnosis. Prader-Willi syndrome was literally the last thing they tested her for.

Tessa ~

Finally, my dad got diagnosed with ALS and Frontal Temporal Dementia. But by then he didn’t have health insurance because he’d been let go from his job. And his crazy schemes had lost so much money. I didn’t know how we were going to afford it. His healthcare, I mean.

I finally found a nursing home to take him if he got on Medicaid. But to get on Medicaid, you need bank statements from the last five years. I knew his current bank, but had no clue which bank he’d had before that. I basically had to make a list of every local bank, walk in, and say, “Did this person have a bank account within the last five years?” And I’d show them my Power-of-Attorney papers. There was no other way to do it.

Ten banks rejected me before I found the right one. I was so relieved…until that man, with that stupid little mustache, came back and said, “You’re missing one of the Power of Attorney pages. We can’t give you the records.” Well, I started crying right there in the middle of the bank. I sobbed my whole story through tears and snot. Finally, he was just like, “Okay, okay, I’ll give you what you need. Just stop crying!”

So eventually I got my dad into the nursing home. I was still taking care of him though. You’ve got to keep an eye on the staff. You’ve got to make it clear that someone’s holding them accountable. Because they will do whatever they can get away with. I even had to teach the nurses how to get him out of bed. They were lifting him by the arms. The arms! With his ALS, that was the most painful part of his body. And I thought, “If they’re messing up when I’m around, what are they doing when I’m not?”

It wasn’t just the nurses. Uhhggg, the doctors would ask him all these health questions and then stare at him like they were expecting to get some legitimate answer. And I’m just going, “You want his answer? Or the truth? Cause if you want the truth, you should probably be talking to me.” I had to take him to the hospital once for severe rectal bleeding. The doctor asked my permission to do an endoscopy, a colonoscopy, every oscopy you can think of. He said it might be cancer. So I’m like, “If you find cancer are you going to save him?” And he said, “Oooh, well, no but…” Then why put him through those painful tests if he’s already dying? You’re going to make him suffer because you want money? No. Leave him alone. I just want him to be comfortable.

Carrie ~

Two years ago, I was walking outside my apartment, and tripped. That’s all. I tripped and broke my patella bone! Well I was healing, slowly, and then I tripped on my crutches and cut my face open! You see this scar? I needed twenty stitches! And I hurt my knee all over again. The doctor said this happens all the time because crutches are so hard to use! But anyway, I’m not even sure I believe in doctors anymore. My physical therapist has done a thousand times better for my knee than any of the doctors.

The medical system is so fucked. Like with my dad? When he was first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s? I’d stop by once a week, make sure he had groceries and everything. But he got worse and I started coming every other day, then once a day, then three times a day for all the meals. It was my whole life… One night, I get to his house after grocery shopping, and I call, “Daaad,” but he doesn’t come. So I’m frantically screaming his name, expecting to see him lying on the floor. And I can’t find him anywhere. I assume he’s wandered off and gotten lost, you know? I call my friends; we’re running around Evanston searching the streets. I’ve called the police, and three hours later, we can’t find him anywhere.

So I’m lying on the kitchen floor, sobbing, when Dad just strides through the front door with his head wrapped in bandages. Apparently he tripped on the sidewalk, his glasses cut his face, and the neighbors called an ambulance. They never even bothered telling me. And then the hospital! He wears a bracelet saying he has Alzheimer’s, with my number, and no one called. They sent him home—alone. They just stitched him up, wrapped his head, and told him not to lie down.

I was so pissed. I called the hospital and I told them they’d made a big mistake. I told them if I had more time and energy, I would sue their asses. He had a medical bracelet and they never even called. At least they waived the medical bills, which saved us a few thousand dollars.

Amber ~

Andrew was diagnosed with Down syndrome before he was even born. The doctors suggested my mom have an abortion, but both my parents are pro-life. My mom actually had her tubes tied after my first two younger bothers were born, but my dad said, “If a vascular surgeon can’t have a ton of kids, who can?” So she had the surgery reversed, and had Andrew. After Andrew was born, she wanted more kids so he’d have younger siblings to play with, since the first three of us were so much older.

Tammy ~

The second Andrew was born I saw the doctor crossing her arms, shaking her head, and looking at him. She was Indian. They don’t understand why we have Down’s kids. In India, basically they’ll kill females. So a retarded child, why even have it? It’s not a fun thing, when you just have a baby and see the doctor shaking her head.

I had a blood test. Can’t even think of the name, it’s been so long. They said it came up normal. I had no idea. Except he was smaller. I thought, “God, I’m not gaining weight like I did with the others.” Makes sense though, cause they’re little people.

The hospital sent a representative from the Downs National Alliance. She came in all cheery telling me it’s not as grim as the public thinks. She was right. He’s one of my easiest kids. And the Alliance people say there’s a list as long as your arm of people willing to adopt Down’s kids. I said, “Really? Cool, but I’m keeping him.”

Naomi ~

The doctor said, “Do not look up Prader-Willi on the internet!” So of course we did. And what we found, it was just, it was just…devastating. Severely obese children eating themselves to death. Parents finding their children eating garbage, or getting calls in the middle of the night to say their kid had broken into a store to steal food.

I have had weight issues since I got pregnant the first time, so it felt like an insatiable appetite was probably worse than any other disability my baby could have. I waited for years, dreading the night I’d come downstairs and find her stealing food from the refrigerator, or worse, eating out of the garbage. I wouldn’t want to go downstairs in the middle of the night for fear of it beginning.

But it never did. To this day Caroline has never eaten anything I haven’t given her. She’s eighteen now, and it was definitely a trade-off, but I’d take the way it turned out over the alternative any day. You see, Caroline’s IQ is lower than most kids with Prader-Willi. She reads at a seventh grade level and math is much lower. So we could…brainwash her, kind of. Ever since she was four, her breakfast, lunch, and dinner have been the exact same food, same portion, every day. And since her cognitive function is so much lower, she doesn’t question it.

Most kids with Prader-Willi turn eighteen and realize that they have free will. They emancipate themselves and within three or four months, they gain a hundred pounds. There’s nothing the parents can do about it. Usually, they die. We’re not going to have to go through that with Caroline. I’ll take our situation any day.

Of course now, with her peers going to college, and prom…it hits home. She’s not going to do those things. But it’s a lot harder for me. Caroline always says, “I’m the luckiest girl in the world!” That’s how she sees it. She wakes up happy, she goes to bed happy. Her quality of life is damn good.

Tessa ~

If I wanted to go on a date, I had to stop by the nursing home first to check on Dad. If I wanted to go out with my friends, I had to stop by the nursing home first to check on Dad. And then I’d be at this hip bar, drinking a fruity margarita, surrounded by my dolled-up friends, and just feel…miserable. I was a real downer. I’d spend the whole outing wishing I were at home, being a downer alone.

Carrie ~

I don’t talk to my siblings anymore. I’m the only one of my father’s six children who did anything for him. My brothers were all too busy. Towards the end of his life, my dad started asking for my sister. She agreed to Skype with him. But after the second time she said she wasn’t going to do it anymore, because she wasn’t getting anything out if it. We haven’t spoken since.

Amber ~

Once Andrew turned twenty-one, he was too old for public school, so my dad put him in a home. It’s okay I guess. I wanted a nicer home for him, but I don’t think he minds. The really nice homes have twenty-five year wait lists. We had to find this one at the last minute, because it was always the plan for my mom to keep him at home. But she wanted to get far away from my dad, and when she moved to Vermont she lost custody of Andrew. So now I do most of the caregiving. I handle emergencies. On weekends I bathe him and cut his nails. The home’s supposed to do it, but he hates water so they don’t force him.

Tammy ~

I think Andrew is happy. My son Michael says, “Mom, Andrew likes to go to dances cause he’s with his homies.” Michael stayed and watched once, and said Andrew gets out in the middle of the dance floor, takes the microphone, lifts his shirt up. He’s got a big pasty-white belly, and is doing a belly dance in front of everyone. “He’s like a different person with his homies,” Michael says. “Like he knows those are his peeps.”

Amber ~

I end up doing most of the work because my brothers aren’t married and go out on weekends. I’ll call and say, “When did you speak to Andrew last? If you’re in town you should see him.” And they’re like, “Oh yeah, I should do that.” And it’s like “Yeah. You should do that.” In most families one person becomes the caregiver because it’s just easier that way. If you had six people responsible for Andrew, and communication wasn’t perfect, it would get really confusing.

Naomi ~

I’d keep Caroline home forever if I could, but she’s such a social kid. We’re looking to find two or three other families with special-needs kids and buy a house where they can live together. With a fulltime caregiver, of course. We’re lucky we can afford to do that.

My son’s been wonderful. My husband, too. Don’t get me wrong, Grant drives me nuts, but he’s so good with Caroline. He’s really been my partner in all this. Of course, Caroline gets a lot of her bad habits from him. Like licking the yogurt off the top of the lid. Well, that might be a Prader-Willi thing, but Grant does it, too!

If I were asked to give advice to parents of a Prader-Willi baby, know what I’d tell them? Nothing. Caroline is skinny, she’s never stolen food, she’s the only kid with Prader-Willi and a nut allergy to survive. I don’t want to give false hope. Our happiness is so rare.

Tessa ~

Everyone says, “I can’t believe you did all that. You’re such a wonderful person.” First of all, I didn’t have a choice. There was no one else to do it. It’s like you don’t realize what you’re capable of until you’re faced with it. And then you just do it. I still struggle with the guilt of wasting so many years hating my father because of that affair. I couldn’t have known what was causing it and all, but still…

You know, when we got the diagnosis, it was almost a relief. Especially for my mom. For all those years he was lying, she kept asking, “What did I do to make him cheat on me?” When we found out that his behavioral changes were a symptom, it was like a million weights had been lifted off her. It all made sense. It was nothing she did.

My mom even visited him in the nursing home. The way his face lit up, she knew he remembered her. She was sitting in that old mauve chair, the one that spilled out stuffing, tenderly spoon-feeding him clumpy rice pudding. “I forgive you,” she told him. “I’m letting this go.” And that was the greatest closure.

Carrie ~

There are two kinds of people. Those who can handle it, and those who can’t. Don’t get me wrong, I think the second kind are ultimately selfish, I’m not defending them. But I will concede that it’s hard to see your father sick and not be the man you grew up with. Since it’s hard, they leave. Anyway, my brothers didn’t care and my sister was too selfish. I was the only one at his funeral. Eight years of caregiving left me drained in every way. It’s been three years since he died, and I’m still tired, but I’m starting to feel like I have a life again.

Amber ~

It’s hard for people to relate when I tell them my brother has Down syndrome. They sympathize and say, “Wow, that sounds terrible.” But they can’t understand. My friend has a cousin with Down syndrome. And finally I could say, “You know what it’s like!” It’s a relief to meet people like that. They reaffirm that what you’re doing is hard and taxing, and difficult. But it’s something you do because it’s family and you love them.

Every aspect of your life becomes: how does this impact the person I’m caring for? My husband and I want to move out to Portland, it’s been my dream forever. But as long as Andrew’s here, I can’t leave him with my dad. I have to put my life on hold until I can bring him with us.

Tammy ~

People say, “God knows who to give those kids to. You’re so patient.” And I’m like, “It’s not like there’s an option, okay? You’re given this and you deal with it. I’m not any more special or any more patient than anybody else. I don’t have a choice.” God, I’m so sick of people saying things like that. If you had one you’d deal with it too. Cause you have to. You don’t have an option. They’re family. What are you going to do?

Katherine Koller is about to begin her career as Development Fellow for a nonprofit in Chicago called Peer Health Exchange. She just graduated from Northwestern University, where she majored in theatre, with a concentration in performance, activism, and human rights, and a minor in creative nonfiction writing. In addition to her coursework, Katherine spent three years teaching Pregnancy Prevention in Chicago Public Schools with Peer Health Exchange, and was the Executive Director of a Northwestern course in consulting for nonprofits. She loves the theatre, and acted in many campus theatrical productions.