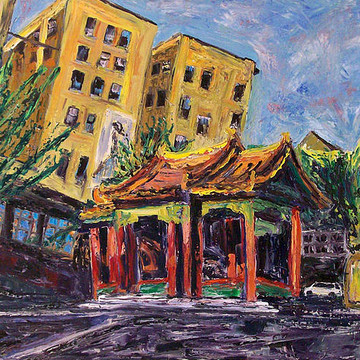

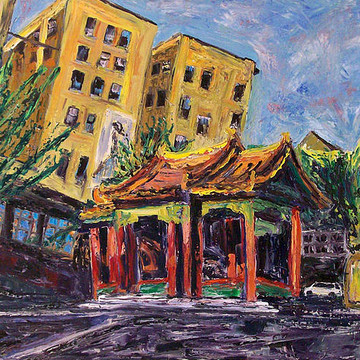

Seattle, Asia Town Temple,” by Allen Forrest, oil on canvas

“My life led by confusion boats, mutiny from stern to bow/

I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.”

—Bob Dylan, “My Back Pages”

When I began working at Pinnacle Community Recovery Center,[1] I was unemployed and squatting at a friend’s apartment located two blocks from Lancaster Regional Hospital, in Pennsylvania, where I’d been born 24 years before. I often remarked then how this symbolized what a waste my life was, resulting in my friends’ designating me with the appellation “Killjoy.” During this period, I slept on a couch in unfurnished rooms all day and drank and snorted Percocets every night, looking for coins under couch cushions to buy cigarettes from friends. I had neither girlfriends nor job prospects, because I had never graduated high school, and had my license suspended for a DUI whose specifics are still too embarrassing to reveal. As a part of the DUI punishment, I was assigned a probation officer who encouraged me to take advantage of her career networking connections, because, as she argued, if I remained unemployed I would keep drinking, get another DUI, and wind up in prison, a prediction I smirked at then.

She found me a position working for an agency in the mental health industry. The job title was Human Health Aide and the job description to model appropriate behaviors and assist clients with Activities of Daily Living, including cleaning, cooking, nutrition, and social engagement, for mentally ill clients. The irony was that I myself didn’t model appropriate behaviors—I dressed in ragged Goodwill clothes, I smoked and chewed tobacco, I lived on gas station hot dogs and, when I met a girl at a bar drunk enough to fuck me, never practiced safe sex. The job paid $8.25/hr. When I told everyone at the bar that night they laughed and asked if I were sure I’d been hired by the agency or committed to its facility.

At that point I was against everything that reeked of success, happiness, or ambition. Since I had been hospitalized for depression at 14, I had developed a romantic vision of suffering, creating a narrative identity around such cultural icons as Kurt Cobain, Sylvia Plath, and Friedrich Nietzsche. In my few cardboard boxes of possessions I humped from couch to couch, from week to week, I stacked depression memoirs by Wurtzel, Slater, Jameson, and Styron, comparing their experience of depression or substance abuse against mine, feeling superior because my dysfunction and negative attitude about the world appeared, at the time, greater, more resolute, and thus more meaningful, than the symptoms and experiences they described. In other words, I was depressed and hopeless and without plans for the future, and never thought for a second that there was something problematic about this, or that there was another way of experiencing the world.

I was in no position then to be a Human Health Aide. Almost daily, I made stupid mistakes or showed errors in judgment so egregious that the Program Director called me into her office and asked if I was “on” something. Often, in the earlier days at least, her suspicions were accurate, and had I been tested for drugs or alcohol I would have been sent to prison, as my probation officer had warned. But luckily this never occurred, and the Program Director slowly acclimated me to the program, giving me permission to drive the facility’s unparkable Aero van, teaching me the “Recovery Movement” philosophy, and encouraging me to read up on each patient’s case history in the massive blue folders locked in the main office desk. Looking back, I suspect she was protecting the clients from me, based on her suspicion my presence around them would be detrimental, that I would behave inappropriately. I had to exhibit appropriate communal behaviors to her before I could be trusted to model them for clients.

Pinnacle Community Recovery Center’s mission was to assist adults with mental illness to transition back into the community and, ultimately, re-learn how to live independently. Usually these clients had been committed for protracted periods in state mental hospitals, and arrived at the facility with diagnoses such Borderline Personality Disorder, Schizho-Affective Disorder, Major Depression, and histories of suicidal acts and ideation. Almost all had co-morbid substance abuse issues, as well. I shouldn’t call it a facility, which implies inpatient treatment or locked doors—rather, Pinnacle was set within a community of small apartments and vinyl townhouses, with our clients living semi-independently next to college students and young married couples in distinct, private units, in most cases 1-bedroom or studio apartments that had stains on the floor and smoky brown rings on the ceiling. Our office was a townhouse located in the middle of this diverse neighborhood, and from the roof, if you went up there to smoke a bowl during an over-night shift, you could watch as all the lights went out early in the clients’ apartments and stayed on all night when the college students partied.

When the Program Director finally let me loose from the office, I felt like I had undergone a seminar in advanced psychology, pathopsychology, and, in particular, the ethos of the Recovery Movement. Although prevalent and well-respected now, the recovery movement was then in its infancy, and most of the support staff at Pinnacle—especially the clinicians, the psychologists and psychiatrists, those with Master’s in Social Work—were wary of its “lax” approach, suspicious that without maximal supervision the clients would decompensate and return to the hospital.

I’d be lying if I said this didn’t happen in some cases. In fact, my first time driving the facility’s massive Aero van occurred when Del M., a paranoid schizophrenic, was accused of attacking[2] a neighbor’s daughter and was committed to Lancaster Regional Hospital’s psych ward. While I was filling out the 302 involuntary commitment report, I realized this was the first time I had been in the hospital since I was born, when it was still called St. Joseph’s Hospital, and my mother and father, proud Catholics, held me in their arms, radiant and flushed, thinking of all the potential that I had, wondering what amazing things I would accomplish as an adult.

In the meantime, I settled into a routine at Pinnacle. In the mornings, I’d heft the canvas bag of medications in EZ-Dose packets and patient folders towards their apartments, walking past kids at the bus stop and men my age kissing their wives good bye in the driveway. I’d ask the clients to identify their medications and initial in the Medications section of their binder that they had ingested their meds; if they did not wish to, they were to sign with an X, which happened about 5-10% of the time. When this happened with a controlled substance like Percocet or Xanax, I’d consider forging the X into an initial and pocketing the pill, which my friends all requested, but by this time my own recovery had, gradually, begun to bloom, like those flowers on the side of my mom’s bed in the picture of her holding me as a baby at St. Joseph’s.

Each client taught me something different, and to this day when I ably go about my activities of daily living (on certain days, that is), I think of what specific client taught me about how to live. Along with another client, Ron R., I had enrolled in community college classes, which we would attend together in the section of town where most signs were in Spanish; we were in fact the only two Caucasian males in the class. When I drove clients to the daytime clinic, or waited outside when they met with their counselors, I would study in the van, and doodle questions in the margins for Ron R., who had an IQ of over 140, to explain to me later.

There was Susan H., an older women with Borderline Personality Disorder and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, whom I would take grocery shopping. Because of her infirmities, it was my job to split shopping duties with her, her scrawling half her recipe list for me to run around and scavenge while she swerved around in her motorized cart. She taught me for the first time what a serving size was, the differences between kinds of potatoes, and how to use coupons. Before then, my shopping trips were usually split between the frozen food section and the liquor store. She taught me the virtues of vegetarianism, which I follow to this day.

From Sienna M., who suffered from HIV and unipolar depression, I learned how to cook Spanish food, how to clean a kitchen without just throwing water on the floor and wiping it up with paper towels attached to a baseball bat. She had a teenage daughter who would come visit on the weekends, and I would talk to this daughter, herself depressed, about what I went through when I was her age, and how she should be proud of her mom. Sometimes her daughter tried to sneak a boyfriend over with a six-pack and I would have to roll off the air-mattress at the office and confiscate the materials, not telling anyone so Sienna wouldn’t be sent back to the hospital or lose her already slim custodial rights.

After a year I’d saved up enough money to rent a studio apartment. I filled it with community college textbooks, an old Dell desktop from the office, furniture from Rent-A-Center, and started cooking meals on my own and washing the dishes in the sink, appreciating the relaxing, Zen-like motions of manual washing. Every night, while filling out the daily progress notes for each client, I would seek for the right word, the apt turn of phrase, to not just communicate to my colleagues any important happenings, but also finding joy in the rhythms of writing, and began registering for community classes in creative writing and English to improve my writing abilities.

We all still messed up, a lot. This is one of the things we had been instructed to tell the clients, that recovery was a process, not an outcome. I remember so many nights sitting on Neil W.’s couch listening to him cry about his divorce while he injected his insulin, or sitting in the dark humming with Chi T. when it rained, because she had grown up as a little girl in Vietnam and had traumatic flashbacks to her childhood in these cases. I learned that caring is a muscle, compassion is an exercise, and the more you care for other people, the more you can begin to care for yourself, to work for health, to strain for goals—but at the same time, while everything seemed to be going so well, I felt like a sell-out, as if I were betraying my friends, my depression memoirs, my habit of laying in bed all day, my youthful nihilism.

Every Saturday we had a communal meal at the office. Each client would be assigned something based on his or her functioning level. Sienna, of course, would bring some delicious zesty Spanish dish whose names I simply can’t recall, while others might bring a six-pack of diet soda or frozen rolls they had heated up in their ovens, usually with my assistance, although it’s probably clear by now that they knew far more about ovens than I did (I didn’t use an oven cleaner until I was 26). These Saturdays would follow the frenetic Fridays, when they received their minimal SSDI checks and we would hustle to get to the bank and the pharmacy and the store and back in time for 8 PM meds. Most of them spent half their money on cigarettes, which I had quit smoking by then.

Of all my guardians, of all these angels whom life had cursed, whose childhoods were abusive, whose brain-chemistry was dysfunctional, who just never got any help before it was too late, Jason S. strikes me now as my possible double. He was my age, more handsome and intelligent than me, and alienated from most of the group, who tended to be at least 40 years of age. He had an ex-girlfriend far prettier than any girl I’d ever known who would come visit him every week and take him out to a movie or dinner. Sometimes, I found myself being jealous of him, but we quickly became friends. In the space reserved for a dining room table, he’d erected a tiny workout station, nothing much, some dumbbells, a stationary bike, a device he attached to the door to do pull-ups. I began working out with him, the two of us pretty much equal except for our brains, and it was then that I realized that there were two kinds of mental illness, one a cultural performance (as I had wasted my life on) and one a mystery of synapses and tragic incidents, which had been the case for Jason.

My “recovery,” therefore, was a result of working with the clients in the program, who were my models; my recovery was pure luck, my survival pure luck, such that I look back now on that night of the DUI (which I blacked out) as a pivot in my life, a low moment requiring correction, a redemption offered to me by the clients at Pinnacle. And while I still appreciate the music of Cobain, the poetry of Plath, the dark musings of Nietzsche, I see them now not as functions of depression, but something to be respected precisely because these people fought against depression to create something beyond the banality of suffering. In the end, those who were most victorious were the clients at Pinnacle, straining minute-by-minute and day-by-day to stay out of the hospital, to make a new life, to find a niche in the world that makes sense, that works.

Convention dictates, I realize, that I’m supposed to include here an anecdote about meeting an old client over tea, where we discussed how improved we were, but that never happened. The closest to that happening was a client seeing me at a 7-11 and, without recognizing me, holding out a handful of coins and asking for cigarette money. What I realize now is this: it’s not a lie that people can’t “recover”; rather, it’s that the supposed meaning of the concept is misunderstood. The nature of recovery is bilateral, trilateral, communal—my clients, in the end, modeled appropriate behaviors for me through their toughness and sobriety and honesty, their dedication to revise their life stories to account for trauma and disappointment, which I never had done to account for my mental hospital stay when I was 14. Even though I’m far from recovered now, when I work on my Ph.D. dissertation about narrative therapy, the concept that telling stories is by its very nature beneficial, I often pause and stare off, out the window into that perched past, remembering studying English with Ron R., and then return to revising my chapters, seeking for the right word, the best rhythm, the most accurate description, the same way as when I started writing in Pinnacle’s office, recording clients’ progress notes in their blue, oversized folders, attempting to find a narrative in those back pages.

James McAdams has published fiction in decomP, Literary Orphans, One Throne Magazine, TINGE Magazine, Carbon Culture Review, and Copperfield Review, and has additional pieces forthcoming in per contra and Modern Language Studies. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in English at Lehigh University, where he also teaches and edits the university’s literary journal, Amaranth.

[1] In order to avoid possible HIPAA violations, names of facilities, clients, and staff members have been changed, while their characteristics, personalities, and narratives have been strictly retained.

[2] He claims he was trying to help her with her shopping bags, which I still believe, but as a result of his tardive dyskinesia he trembled and often lost balance, seeming then to grab or lunge against people in aggressive or sexual ways.