“She Drove” by Peter Groesbeck

The hegemony of the domestic epiphany is unchallenged by the irrefutably frequent but characteristically flimsy foreign epiphany (rigorous epiphanies, like automotive mishaps, occur most commonly within twenty miles of the epiphanee’s domicile); however, for Americans in thrall, it is rare for the physical venue of the catharsis to be commensurate to the experiential phenomenon.

Tera is a failed academic and knows how to Latinate-up a sentence, how to wield the unwieldy phrase, how to turn tango into partnered bidirectional ambulation.

The weightiest secular kenotic incidents of American existence habitually transpire in strip malls (augmented by muzak soundtracks), at sporting matches (while seated beside adults adorned in giant spongy caps), or in garish hospital waiting rooms where, while the beloved is expiring in an adjacent room, Extreme Makeover cannot be shut off or turned down no matter with whom one pleads.

Tera is in that waiting room right now, witness to a forty-something woman at the Makeover Mansion saying she wants to flatten her jug-handle ears and de-flatten her pugilist’s nose. The woman looks a lot like a koala bear, and Tera cannot help but root for a successful metamorphosis. On the other side of the thin wall against which her vaguely purple chair rests, her husband breathes by means of mechanical pump. Electrodes taped to his chest translate the fragile rhythms of his heart into a language only an M.D. can decipher. The doctor will use cartilage removed from Koala’s ears to prop up her blunt nose. Tera’s husband will not live into next week. He may not make it to the morning.

Tera tries to concentrate on her laptop despite the insistent televised distraction. Her task is to explain the unexplainable, and there’s not much time.

Does the democratization of the American epiphany minimize its efficacy by systematically situating it in culturally debased locales, including, but not limited to, corporately franchised refectories?

She decides to revise the sentence.

I had a vision, she writes, in a fucking Hardee’s.

~

The toll road was direct and unwavering, without curve, detour, or intersection—so elegant in its ugliness that the Hardee’s island seemed a betrayal, like finding a caged animal in the wilderness. Tera entered the cage and ordered a slab of meat on a bun, a barrel of iced tea, a boat of fries. “I’m not that bad,” she was saying, talking on her cell from a plastic booth. This was the early days of cell phones, and it was roughly the size of her foot. “Just the front fender on the passenger side, but I can’t drive it, and I certainly can’t pick up Dmitry.”

“That’s where you’re going?” The speaker warped Kenny’s voice, erasing the highs and lows, and yet she could have identified him after only a couple of words. Here was a new skill for the dying century, she thought, the instant recognition of vastly distorted things. Kenny continued: “You used to be a good driver.”

“I used to be a lot of things.” A list formed in her head: safe driver, faithful wife, honest friend. “What I used to be is beside the point.”

“Why are you calling me?” he asked. “There are a few billion people in the world who aren’t me.”

“I dialed everyone else in my book.” This was a lie, but he knew her tendency to exaggerate. It felt more like an offering. “You’re the only one who answered.”

Springtime in Kansas is brief, like the expanse of days a baby crawls: amazing when it finally arrives and over before you know it, summer vaunting in upright, sweat running down its pale thighs. This day, though, belonged to no season. The afternoon sky was the brown of upturned earth, as if the heavens had been recently plowed. Tera had pulled off the highway to answer her cell phone, but a boulder hiding in the grass bent the fender against the tire. The call was from Dmitry’s sister. Tera had let it go to voicemail and hiked to the Hardee’s.

“I’m the last person your husband will want to see,” Kenny said.

“He doesn’t know it’s you. He just knows it’s somebody, or it was somebody.”

“Buy you said—”

“I didn’t provide a name. I didn’t want him to hate you. Look, I’m already late. If you can’t do it…”

“You know I’ll do it.”

“I’m at that Hardee’s on the toll road. You know that Hardee’s?”

“Everyone knows that Hardee’s. Where’s your car?”

“It’s not in a ditch, exactly. You’ll see it.”

“You should have called me from your car. That’s the point of cell phones.”

“Just get here before I’m tempted to buy horrible food.” She let the phone clunk against the table and stirred her shot glass of ketchup with a wilting fry. The building stank of grease and despair and miles to go before anyone might sleep, as if the cushions in the stalls had absorbed the loneliness of the travelers who had cursed the greasy food as they stuffed it down.

The accident—if it was significant enough to be called an accident—had taken place an hour earlier. Tera’s first thought: perhaps it was a way to avoid the remainder of the trip. Dmitry’s sister could pick him up. But there were papers to sign, and she wasn’t sure they would release him to anyone but his wife. She had obligations to keep.

“You want a refill?” The boy’s face was freckled, chubby, and round. His colorful shirt held a narrow rectangular grease stain like a tiny grave. He scooped up the burger wrapper in a furtive gesture that conveyed nothing but shame—his or perhaps his recognition of hers.

“Sure,” she said, and he grabbed her sloshing tub of iced tea. Three months had passed since the night she officially drove her husband crazy. Dmitry had insisted that she was seeing someone else, no matter how expertly she denied the accusations. Earlier in the day she had taken the dog and walked to the park where Kenny waited in his car. By the time she got home, it was dark and she reeked of sex, and the dog was not only frisky but almost frenetic, and Dmitry said, “Tell me the truth or I’ll hang myself.” It might have sounded silly if not for the noose swinging from a ceiling beam.

“It’s a man from work,” she said, sticking to her strategy, which was deny, deny, deny, and failing that, lie, lie, lie. She worked in the mayor’s office, an organizer for the so-called great man. “You don’t know him,” she added. “He was only here for the election.”

“Tell me who it is,” Dmitry insisted.

She named a man she hardly knew, a consultant who had returned to Topeka, a person Dmitry would never see again. “Now take that down.” She indicated the noose.

He obeyed but didn’t sleep that night or the next. After four nights without sleep, he didn’t know who Tera was. He couldn’t dress himself. He wept in the tub. With the stay at the funny farm, Dmitry had officially climbed aboard the psychobabble express, a nonstop local with connections that could take you anywhere, including a much funnier farm where the gates were always shut. After the farm spat him out, he would be suspect. His colleagues who were now in agreement about holding his position for him, would shake their heads and speculate cruelly if a student complained or class went poorly. A trip to the funny farm to get well was like bathing in ink to get yourself clean.

The freckled boy plopped the cup before her. The specks on his face were allotted unfairly, with twice the density around his eyes, as if they were geysers. He had filled her plastic cask with Coke: half-tea, half-soda, an unholy mixture that tasted of sweetened mud. Before she could say anything, he swept past her, joining the others of his tribe—four portly souls in hideous Hardee’s uniforms standing at the window and staring at the sky: The Hardee’s Boys.

Tera realized she was the only customer in the place.

“If that’s not a twister,” said one of the Boys, “then I’m the next president of the United States.”

He didn’t look like White House material. You work a few campaigns, and you know.

~

Tera’s former lover flashed his lights, and she ran out into the parking lot. The wind was blowing and she let it lift her skirt, pushing it down a second too late and laughing. She was thirty-three and could get away with such things for only a few more years. Her advantages were on the wane. Of this, she was painfully aware.

She slammed the car door on the wind, smiling at him, her hand on her head as if it might fly away.

“This is crazy.” He wheezed out the sentence as if there were an arrow in his chest. “What am I doing here?”

“I asked you.” She gave him a lingering kiss. His cheek was as dry as the skin of a lemon.

“I suppose it’s efficient,” he said, rubbing his cheek and eyeing the fingers. “You can torture both of us with one stupid act.”

“Did you see my car?” she demanded. “It’s not like I was aiming for that rock.”

“I don’t see how else you could have hit it.”

“We should go. The wind is picking up.”

“Tornado warning,” he said. “Heard on the way over. Would’ve been nice to know before I drove into the middle of it.”

“You didn’t use to be such a whiner.”

The Hardee’s Boys turned their attention to her lover’s earth-brown sedan. How could they possibly be more interesting than a tornado?

“Don’t wreck my car,” he said, unbuckling, “and don’t leave me here.”

“Oh, come on,” she said. “He has no idea it was you.”

“No hurry.” He raised a thick novel. “I’ve always meant to read Proust.”

“You have not.”

“Three months of nothing,” he said, pushing the door open an inch, “and when you finally call, it’s to pick up your husband.”

The wind caught the door and yanked it open. He hunched against the torrent and bent low to walk. The Hardee’s heads followed his serpentine approach.

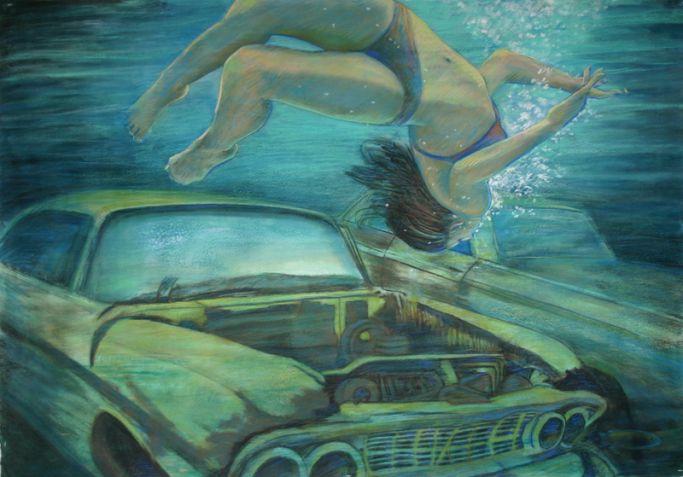

Tera slid over and started the car. Hanging from the rear-view mirror was a disco ball that might have been a road hazard, refracting light everywhere, if there had been any noticeable sun. She had never driven the car, but she’d had sex in the back seat, parked on the street in front her house—Dmitry’s house, really, his before they married—and Dmitry was inside, asleep, she’d thought, but when she went into the bathroom to tidy up, he was there, shaving. She slipped out and went to the guest bath. She hid her clothes in the bottom of the hamper, in case he decided to come in and smell them.

All the lovers she’d ever had in this weird plot she called her life—teenage delinquents, twenty-something narcissists, a couple of college girls, men in their golden years, and Kenny—would never appear in the same police line-up. Each was a bup to her kiss, but her kiss had gone through a lot of changes. Which suggested her essential problem with marriage: the woman she was when Dmitry married her and the woman she had become were related, but only in a half-cocked manner, like the relationship between a cow and a burger.

Within the first mile, she realized she had a problem. The car was shifting on the road. Making it to the funny farm would depend largely on luck. But she was used to that and didn’t turn around. The sky turned a shade of green reminiscent of a baseball park—a too perfect green that really really really did not belong in the sky. She had put herself in mortal danger for spite. Three months earlier, she had broken up with Kenny for no reason but the sudden onset of shame. As soon as her husband was hospitalized, she cut her lover off. With Dmitry in the funny farm, Kenny’s tongue in her mouth carried a residue of vinegar. She wouldn’t have called him today but she needed a ride.

Or so she told herself.

The drive to the funny farm is something that she has carried around like a wristwatch, a little ticking reminder that she was once fearless and stupid and incomprehensibly vain, and that two men had loved her enough to ruin their lives. It mortifies her and she treasures it.

She punched buttons and her cell played the voicemail from Dmitry’s sister: If you take my brother out into a tornado, I’ll have you arrested. You hear me? His sister had never been what you might call welcoming. She was like a child who did not want to see her mother replaced by some mere person, only Tera was just a sister-in-law. Dmitry’s first wife had been the kind of stand-up gal to drink scotch on a bar stool, wearing a dress that was fashionable without being desperate, in smart heels that reminded you she was still a sexual being no matter her age. She had been a reporter for decades, and then she wrote restaurant, theater, and movie reviews. Dmitry had loved her in a manner Tera could not fully imagine, and his love for Tera did not approach it. Oh, he doted on her, but the dead woman had been his equal, his partner, his match. Tera was the pretty face and pliant body, the easy patch of road after the glorious, dangerous switchbacks.

The sky made a human sound, part moan and part sigh, and vaguely condescending. She kept driving.

~

Dmitry sat alone in the waiting room, his hands in his lap making a church with a steeple. The storm evidently had the staff hiding, yet Tera had made it easily enough. The only traffic had been the occasional tree limb, scuttling along. It had almost been amusing.

“I thought perhaps the weather had convinced you not to come,” Dmitry said, standing, gathering his bag. He had lost weight, which emphasized his tendency toward primness. His head was meticulously groomed but his skin was softening. When he pecked the cheek she offered, it was like the touch of wood. He kissed her again, experimenting at some length with her lips, a kiss with a persistent but uncertain agenda, like a bird pulling at gear from a rusty watch. No one burst through the doors to meet her.

There were papers to sign and forms to fill out, and it was absurd to drive in this wind, but it seemed like a fair trade: you may skip the humiliating, hateful paperwork if you’re willing to drive in a life-threatening gale.

Deal.

Besides, if he left without checking out, his sister could sue the funny farm and not Tera.

“I made potholders in a crafts class,” Dmitry said, eyeing a door to the interior, as if he might run back to get them. “Do you imagine they’ll mail them to us?”

She hooked her arm in his and they headed for the door. “You never showed me any pot holders.”

“They say things,” he told her. “Funny things.”

The wind lifted their hair and widened their eyes. They huddled and pushed their way through a dense invisible wall to Kenny’s car.

“This isn’t a car I know,” Dmitry said.

“I had a storm-related accident on the way over,” she said. “I called everyone in my book to get a lift. Kenny came and got me.”

“Kenny Giles?” he asked. “Reliable old Kenny?”

“The one and only,” she said. Kenny worked with Dmitry at the University. He had once been Dmitry’s student. Tera had been Dmitry’s student, as well, a graduate student in Sociology. She had thought she would write an important book about the economic whatsit driving the world market and the international incest and boo-hoo it engenders. But she discovered that her book had already been written, maybe a hundred times. Dmitry set the pile of books on his desk, saying, “Read these. These represent the barrier your dissertation has to surmount.”

It made a big pile, and instead of scrutinizing them, she seduced him, which was a lot less work. She pretty much had him when she started crying—not an act, and yet they were not wholly innocent tears, either. She could still feel that first embrace viscerally, the way clothing holds the smell of the body that has inhabited it. From the first time she saw him, she understood he was a lovely man. He had a way of introducing material in the classroom that was like setting a table. He would prepare an intellectual meal and have you describe the taste. The lessons, ultimately, were never about what you had consumed but the premises that led to your consumption. He was twenty-three years older than she, and his wife had died of cancer the previous summer. “This is in the first-person,” he said when he saw a draft of her first chapter. “Science is not written in the first-person.”

Kenny started the PhD program a couple of years later, a thin, thoughtful boy who moved his hips when he walked as if astride some great animal. He had been small and baby-faced through high school and was not yet accustomed to being attractive to women. They had the same birthday, Kenny and Tera, twelve months apart.

The car rocked in the wind. She and Dmitry were still in the parking lot, facing the funny farm. The place had a huge parking lot, striped by grassy islands, whose saplings knelt before the storm, their bushy heads rattling against the ground like repentant sinners. The storm-light cast no shadows and was hardly light at all, just a dim celestial reminder that darkness was coming.

“They said I could go home,” Dmitry replied. “I would like to go home.”

She turned the ignition, and the wind gave out, as if the gale had been the product of their hesitation. All around them, the tree limbs, mostly denuded now, settled in their familiar poses. A rolling white something tumbled to a stop, becoming a dumpster as it came to rest in a parking place, completely within the lines, as if there were a cosmic plan after all. Tera steered around it.

“We have to pick up Kenny at the Hardee’s,” she said.

“Housework is exploitation,” Dmitry replied.

“What are we starting here?” she asked. “A seminar?”

“That’s on one side of the pot holder—the first one I made.”

She pulled out onto the street that led to the highway. “I thought you said they were funny.”

“That is funny.”

~

The toll road was as wide and empty as the future. The wind had not left them, only fooled them. The storm moved indifferently about them, coiling them in its mad upheaval but leaving the car untouched. They were the last unopened box under the tree, and wrapped in the most salacious porn, but untouched because the box seemed to be empty; which is to say, she was afraid and her mind was racing.

And then every feature of the landscape distorted, as if the wind had made the light crooked, and a gate swing open in her head, a searing snap in the space between her ears, and they were witness to something as elemental as birth, something that defied any human name, a world where trees stood on their branches and walked like men, where a rusty farm implement—a giant thing like bedsprings armed with vicious blades—won the lottery and got to dance weightlessly and gracefully in the trembling sky. With the unlit Hardee’s sign in view, the car took to the air, spun around once, a lateral swirl, as if they were being stirred, and dropped to the asphalt, aimed approximately in the same direction they’d been traveling.

“Be careful!” Dmitry said, roused from some reverie. The whirling car had caused the seat cover to slip free and bunch under their legs like wrinkled skin, as if the storm had aged the car and she half expected to see the paint on the hood turn gray.

“The fucking wind picked up the whole car,” she said. “It wasn’t my driving.”

“The mistake I made…” He paused and she got the car going again, her heart beating in her throat, and she wished the wind would lift them again, shake them like a jigger of gin—anything but hear how she had betrayed him and cost him some share of his mind. “You have to think about sides,” he said. “That there are two sides to every issue.”

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m so sorry.”

“But one side obscures the other.”

“I thought I didn’t love you, that I’d never loved you,” she told him. “I was so disappointed in myself for giving up my studies, and I became convinced that I’d perpetrated this enormous ruse on myself by falling for you. I tricked myself into thinking I’d tricked myself. But when you became ill, I understood that I do love you and that has not wavered since.” Until I was on my way to pick you up from the funny farm and bonked my car against a rock and just had to see my old lover.

At the entrance to the Hardee’s, they could see Kenny and the Hardee’s Boys standing beyond the darkened windows, watching their approach.

“Home ownership is slavery,” Dmitry said, and Tera had a moment to think that he was utterly insane, gone. “That’s on the other side of the pot holder,” he explained, “but the words on one side show backwards on the other, and both sides became illegible.” He showed her a brief, wan smile. “Just like life.”

Whenever she thinks about being in that car, that crappy grad-student car, and watching the sky turn colors meant for the ground—brown and green and the black of topsoil—she pictures the hurled objects and recalls how, for a moment, they were lifted, she and Dmitry and that old Pontiac, and they became objects. They became the hurled. That moment is one that endures—what it means to be thrown forward into the future. To have that much direction is to be powerless.

“American Epiphany, Part II” concludes in the October issue of r.kv.r.y..

Robert Boswell‘s new novel is Tumbledown, forthcoming August 6th from Graywolf. He has published seven novels, three story collections, and two books of nonfiction. He has had one play produced. His work has earned him two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Iowa School of Letters Award for Fiction, a Lila Wallace/Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, the PEN West Award for Fiction, the John Gassner Prize for Playwriting, and the Evil Companions Award. The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards was a finalist for the 2010 PEN USA Award in Fiction. What Men Call Treasure was a finalist for the Western Writers of America Nonfiction Spur Award. Boswell has published more than 70 stories and essays that have appeared in the New Yorker, Best American Short Stories, O. Henry Prize Stories, Pushcart Prize Stories, Esquire, Colorado Review, Epoch, Ploughshares, and more. He shares the Cullen Endowed Chair in Creative Writing with his wife, Antonya Nelson. They live in Houston, Texas; Las Cruces, New Mexico; and Telluride, Colorado. They also spend time in a ghost town high in the Rockies.

Read an interview with Robert here.