“At Last” by Peter Groesbeck

I’ve told a lot of stories about my very brief career in stripping.

I tell my female friends that it was a social experiment and I was doing some late-blooming rebellion. I tell them that it wasn’t very glamorous, most of the customers were awkward but the bartenders were nice.

I never tell my male friends.

To retired and working strippers I tell them that I wasn’t in it long, just to make some money after a living situation went south. Then I change the subject.

I tell the man that I date immediately afterwards that I was trying to prove something and trying to get rid of something. I tell him that I’m not ashamed of it, but it didn’t give me what I needed and it took too much, so I got out. I tell him that a strip club was one of the most depressing places I’ve ever worked in, and I’ve worked retail during the holidays.

I tell myself that I worked longer than I did, that I was better at it than I was, and that I was in control the whole time.

I know that if you tell a story enough times, you start to believe. I wait for that to happen.

While I wait, I keep the shoes in the back of my closet, a sort of insurance I never talk about. If it ever gets too bad, if I am really desperate, I can go back.

Part of me wants to go back. I don’t like how the story ended, it didn’t fit the narrative that I particularly like, in which I play Scheherazade in a T-back. That story takes on a dream-like quality when I tell it to myself, and I do, about a thousand and one times. Hear, oh king, of a young woman who was always good at telling tales. She felt constrained by the stories that were told about her by lovers and her family. She finds temporary liberation in telling stories to men who pay her for the temporary fantasy she gives them. She may not have been the prettiest, or the most experienced, but she was the cleverest and she knew the power of a well told lie. But, time passes and the young woman grows disillusioned with the doublespeak and puts her clothes back on, now wiser and with a wad of cash in her pocket. Finit. There is no room in that story for doubt.

But I do doubt. When I quit, I tell myself it is because I am scared after I see a customer snapping photos with his cell. I also tell myself that I am scared of it keeping me from ever getting a different job. Two years later, I tell myself that if I was really strong, if I really didn’t care what other people thought, I would have kept on going. I had given in.

This is not a good story. I want to rewrite it.

Instead, I write papers towards a degree and cover letters towards a job and credit my success to the fact that I am very, very good at telling professors and interviewers what they want to hear. I treat the whole process like an investigative report—what can I tell them to make them tell me what I need to know to get what I want from them? In between my collection of part time jobs, I start a story about an anthropologist with the super-power to blend into whatever group she is studying. It is a sort of reverse participant-observation—she is observed, and therefore can participate. One day, she looks in the mirror and sees nothing because there is no one there to tell her who she is. I don’t finish the story because I never finish stories.

My unfinished stories are always perfect, just like my unfinished undertakings. I know that I fear mediocrity more than I fear badness. One can be the baddest bad girl, or the worst writer, but to be somewhere in the middle? To try and then fail, not out of lack of effort but simply because when you dragged your sled up the bell curve it teetered then stopped on the hump—that is unacceptable.

One day in a class on research methods the professor makes a joke about going to a strip club, and I wince. I am not ashamed of having done it; I am ashamed of not doing it now. I think, I have given away my chance to be really good at being really bad. I’ve always known that I’m not a good girl; I just play one for the sake of convenience. But I’ve been playing one for so long, I’m starting to forget. Or maybe I believe it. Or maybe it was all a story after all. No—it can’t be a story, it’s needs to be real, it has to be real. I am Scheherazade and all of this is a just a framing narrative mistranslated. The unfinished stories are only a preface, that’s not my real life.

So, a week later when a shiny new friend asks me to pose nude for a performance art piece I say yesyesyes and drag out the scary platform heels and body make-up. I rejoin the stripper forums on the web—I’ve forgotten my old handle so I make up a new one. I make up a whole new set of stories for the occasion that I recite to myself on my way to work. I remember some of the lies I told customers, how I felt like I was a puppet master pulling their sad strings. There is still something dark and jagged fossilized there, but I tell myself it is just a nasty side effect of working in a misunderstood industry and maybe some internalized sexism. A very small voice tells me that this is my chance to prove that I am strong after all. I will tell a story that someone desperately wants to hear. I will finally finish my own character sketch. I will feel whole and real and complete.

I am fitted for the costume that is not clothes. I will wear see through panniers, the type wore by Marie Antoinette before her life went to shit. My hair will be piled up in a style reminiscent of Antoinette also, and I will control a peacock puppet. I’ll wear feathered pasties and a pair of very small feathered knickers. I’m supposed to represent bound womanhood, oppression…perhaps something about class and revolution. I joke and laugh with the artists and feel terribly proud of myself. I have to learn how to attach pasties. At the club we used to get around the tangle of nudity laws by painting fingernail polish on our nipples or sticking pieces of Band-Aid on them. At home, I practice standing very still in the shoes and paint my toenails peacock green to match the new pasties. I will feel beautiful; I chant to myself, I will feel powerful. I will show them all that I am not what I am and that there are so many stories inside of me. I cannot wait.

The performance is at an annual gala for a theatre company. It is at well known bar in a trendy neighborhood, the type that sells cheap beer and microbrews so that customers can affect poverty or patronage, depending on their inclination. The theme of the night is Revolution. In the dressing room a stylist winds my hair through wire pieces, then I take off my clothes and put on my feathers.

One of the artists escorts me to the stage. There is a placard with the title of the piece and my new stage name. There is some confusion when it is discovered that the raised stage I was supposed to stand on is very close to the door. It is an icy spring night and the cold air blows in each time someone goes out to smoke. The artists, trying to be kind, decide that it is too cold for me, and they move the performance space to the floor, near the speakers.

I don’t like being on the floor. It feels too close. I need to be above everyone. But I don’t feel important enough to explain this, it’s not my piece and the move is for my own good. This is a change I didn’t expect; when I stripped I was an independent contractor. I could leave the stage, I could leave the floor any time I wanted. Too much drama would get me in trouble with the manager and wouldn’t make me any friends, but that was up to me. I set the scene. Now I’m a set in someone else’s play. That never occurred to me.

People begin to trickle in. I cock my hip and tug the strings of the puppet. The party-goers walk by. Some stop to stare, some look away. I want them to look, I want to see a reaction. I study their faces, but they are curiously slack. Is it on purpose, out of embarrassment? Or am I just not reaching them? I’m not used to this. In a club, everyone knows what they are getting into, I saw some nervousness, some appreciation, some disgust, but I almost always saw something. When I did figure modeling, the art students always had furrowed brows and pursed lips. Some of the people take out cameras. I wince. I don’t like that. The artists and I never discussed how to deal with photos. I should have thought of that. Cameras make me feel numb, I’m no longer telling a story, someone is taking down an illustration and will write the caption later.

I watch the people watching me, I watch the people not watching me and I don’t feel anything. I rotate the handle of the puppet strings and make the peacock preen and stretch its neck. The motions feel pathetic and small. I’m supposed to tell some grand narrative, what was I going to tell? I can’t remember exactly. This was going to be a revolution but I’m not moving anything.

The room fills. More people, mostly men, take photos. I’m not giving the audience anything, they’re just taking. There is nothing between us but empty space, cameras and an imaginary bird. My feet hurt.

This is all wrong. Not morally wrong, but incorrect, inaccurate. This character, this girl standing so still covered in feathers and other people’s ideas, she is not my story. I agreed to tell someone else’s story, a story about gender and clothing and 18th century class politics but I never really understood the implications of being a character in another’s narrative.

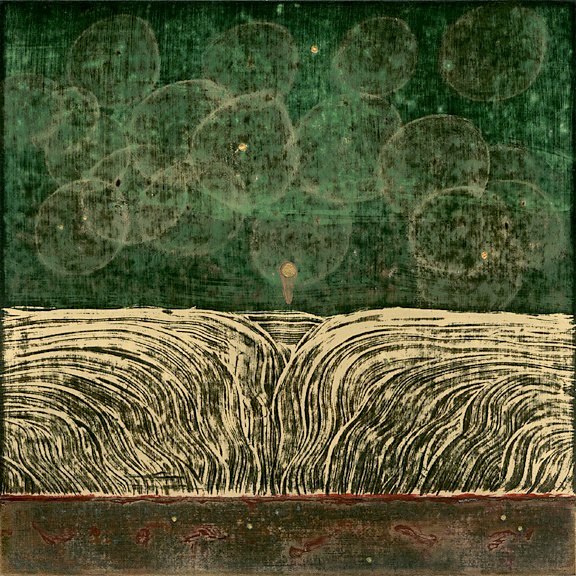

In 1935, Gypsy Rose Lee’s manager coined the term ecdysiast to describe her client’s profession. It comes from the Greek word “to molt,” used to describe invertebrates that shed their outer layer. I wanted to take off my clothes and discover that I was someone better, braver, more talented and beautiful the whole time. If I could just scrub off this layer of mediocrity and failure my life would be better. But here, I just feel naked. Not better or prettier or more interesting. I’m entirely myself from the particular shape of my breasts to the insecurity that clings to me like a birthmark. I haven’t shed anything but my illusions and I am naked as Eve.

I struggle to bring it all back together in my head, to pull the threads of this moment together into some kind of fabric to cover myself. How can I make this moment mine again? I am not supposed to be Eve post-fruit-snack, I am supposed to be Scheherazade on her wedding night and they are supposed to be the king. But how can I be Scheherazade when I can’t finish a story and start a new one? None of my stories are finished. I’m not an artist or a writer or a queen, just a naked girl. That is all that Scheherazade would have been without her stories, a naked girl, then a dead one.

The more strangers tell me how beautiful and daring and “so brave” I am the more ugly and cowardly and I feel. I am facing my naked insect self and I know that this girl isn’t posing nude because she is brave, she is doing it because she is scared shitless.

I stumble home after the event feeling numb and bewildered. I can’t stand to sleep in the same bed as my fiancé, so instead I sleep on our disintegrating couch with an itchy afghan. While I wait to fall asleep, I tell myself the story of what happened. I am ashamed of how horrible I felt. This should have been fine. It was Art and I was surrounded by Artists in thrift store cardigans in a rather well-liked bar while a rather well-known indie band played. I used to strip to bad pop music in a place with sticky floors, surrounded by corn-fed frat boys. I try to find a corner on this puzzle, so I can piece the whole thing together. I need to control the way it is shaping itself in my mind. Every night, I find a version that I can, well, maybe not live with, but one I can tell. It is my bedtime story; I fall asleep repeating it like a mnemonic device. But by the next evening it has fallen apart again, like a book left in the rain.

After several nights of this I call my shiny new friend, bawl her out angrily and incoherently, then sink even more deeply into shame. For God’s sake, if I can’t emotionally deal with something so small and trivial, something I agreed to, then I should at least have the grace not to talk about it. I hate being so exposed; I hate the rawness of it all. I don’t do intimate conversations that I can’t control. I need to write the script, but it is all nasty improvisation.

Before I can pull together a suitable plot, life takes the driving wheel for a while. My fiancé’s stepmother dies, we get married, we move apartments, my sister-in-law gives birth and I start a new job. There’s one thing you can say for death, marriage, birth and work—it fills up your calendar and you forsake navel-gazing for filling other people’s bellies with casseroles.

I take the radio station playing all that noise, pack it up with my spoons and wedding dress and try to just swim through the next few months. When I break through the other side, I still can’t think about it, so I leave it, like the box of photos and old blankets. I mention it to a therapist, and then refuse to talk about it. She continues to bring it up gently, because she’s a bitch that way.

Strange little things begin to happen while I’m not thinking about it. I start telling people no a lot more, which is weird. I find that by truthfully saying no, I can truthfully say yes. And when I tell the truth, writing down things that are true becomes easier. I join a writing group. The writers are awkward as hell but the barista is nice. A few months after writing regularly with strangers, I sign up for some workshops and begin writing more regularly with more strangers. When I read my unfinished pieces I feel ugly and insectile, letting them see the twisty wormholes of my mind, the imperfect cocoons I am spinning. Everyone is very honest and very, very kind. I go home and write more.

I gain 10 lbs. and care more out of habit than hatred. I get rid of about a third of my clothes. I throw away the bottle of perfume someone gave me that smells terrible on my skin. My body still feels like a rental property but now I am building a rickety fence and considering buying a fierce little dog to patrol the yard. I write about the little dog.

And then, on an extremely ordinary day, I finish a story. I am so surprised that I hide it in a file folder that I look at suspiciously for months, expecting it to disappear or catch on fire.

It doesn’t.

When I take out of the file folder, put it in an envelope addressed to a literary magazine and drop it in the mailbox, I am surprised by how little I care. I had read the magazine and it seemed like a good fit, but I didn’t write it for them. The story is mine regardless of whether they choose to publish it.

I tell myself, that was all I wanted in the end, a story that was mine.

A. M. Rose is a writer in Chicago, IL, where she lives with her husband and their bookshelves. She holds a master’s degree in social sciences and spends her days doing research and writing for non-profits and her nights chasing down plots.

Read an interview with A.M. Rose here.