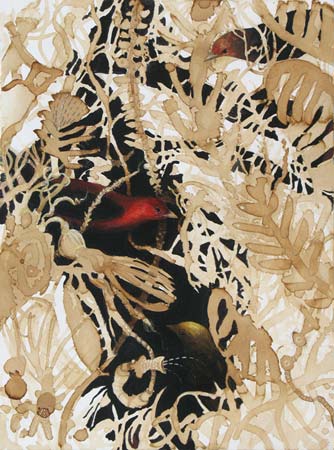

“Little Wing” by Suzanne Stryk, 2005

Home Breast Exam

I handle my breasts in the shower more than an adolescent boy touches his penis. I pretend that I am just washing. I make a round sweep with soap from the outside of each breast to the center, a gentle squeeze of the nipple, up under the armpit and down the side. This is my version of a no-stress home-breast exam. I reason if I wash daily, I’ll notice any lumps, bumps, or changes. Will I?

Stage Fright

Before awareness, there’s a dawning, a sliver of a line between not knowing and knowing—enough space for a dim light to seep in and expose a threat not yet seen, heard, smelled, or spoken. I can’t remember when I first heard the words breast cancer. I’m guessing that it was discussed in whispers before I had breasts or even breast buds. Maybe it was when Phyllis, a close family friend, died from metastatic breast disease when I was ten. I don’t remember anyone telling me that she was sick or that she was dying or that her sickness started in her breasts with a cluster of cells that turned into a lump; this was well before mammograms became a yearly event.

Odd, when you consider that I grew up with a one-breasted bubbie. My mother’s mother lived to a well-ripened age of 91 with a lone plump breast that dangled to her waist and sat opposite a red- and white-scarred flatland, and, yet, I never connected my grandmother’s missing breast with Phyllis’s death.

I recall my grandmother leaning over a white industrial bra and dropping her long breast into the deep cup and nonchalantly tucking a beige pad into the other side. I never asked after a second breast, and no one mentioned that she had once had two. Now, breast cancer would be obvious, but 45 years ago, there were no pink ribbons, pink rubber bracelets, breast cancer walks, postage-stamps, tins of tea, and bottled water screaming out grave statistics.

Back then, breast cancer wasn’t discussed in stages that sounded algebraic—Stage 0, 1, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 3C, and 4, or more typically as Stage 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4. Stages are a shorthand way of discussing severity and survival with few words: Stage 0-1: Very good odds. Stage 2: A little worse but very doable odds. Stage 3: Serious. Stage 4: A life sentence with no cure possible.

I wonder if my grandmother’s cancer was staged as doctors refer to the process now. Would she have been a Stage 1 or a Stage 2? Before the mid-60s, mammograms didn’t exist; any lump or bump was biopsied. Clusters of abnormal cells were studied under the microscope. My 84-year-old mother wonders if her mother had cancer at all.

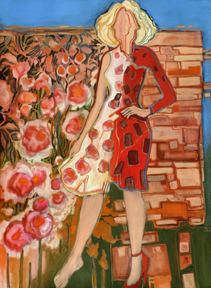

When I was eight or nine, I had a Barbie doll, a Stacey doll, my namesake, or so I wanted to believe. She was a top-heavy straight-haired platinum blonde who couldn’t have been further from my Russian-Jewish genes. Stacey, like Barbie, was sexy if you were into plastic. She was manufactured from 1968 to 1971, which coincided with my infatuation with top-heavy dolls, and measured an impossible 39-18-33—a body that appears naturally only once in every 100 000 women. It’s hard to believe that Barbie, the ultimate shiksa, was created by a Jewish woman, Ruth Handler. (Handler had breast cancer and invented right and left prosthetic breasts. Makes sense. We wouldn’t wear our left shoe on our right foot. Yeah, Ruth!)

Alas, my physical blueprint is closer to a matryoshka, a Russian stacking doll, than to a Barbie. I wonder if dolls will ever be made with a single breast to reflect the reality that some little girls and boys will see when their mothers or grandmothers disrobe in front of them.

Once Upon a Time

In Egypt around 1600 bce, breast cancer, described as ulcers of the breast or tumors, was first detected. Centuries later, doctors began to understand the circulatory system and linked breast cancer to the lymphatic system, the sprawling super-highway of lymph nodes (key agents for infection control), which runs throughout the body. In the 18th century, scientists discovered that this super-highway could also spread disease like a reversible lane on a modern freeway. William Stewart Halstead performed the first radical mastectomy, termed the Halstead radical mastectomy, which involved the removal of the pectoral muscles, all breast tissue, and the underarm lymph nodes; this was supposed to reduce the risk of the cancer spreading. Halstead radical mastectomies were routinely performed until the 1970s, when Rose Kushner was diagnosed with breast cancer and refused the one-stop biopsy and mastectomy surgery that had become standard practice. The journalist challenged the invasive, disfiguring surgery, which had been used for 70 years with no scientific evidence to back up the practice. She made breast cancer into a political issue and pushed for legislation that would offer women choices in treatment. She pushed for coverage of annual mammography by Medicare. She pushed for more dollars for breast cancer research. Her work lead to the change in protocol from the Halstead radical mastectomy to the modified radical mastectomy

Kushner figured out that not all breast cancers are equal. Could my bubbie’s breast have been spared? Was this a matter of your breast or your life, ma’am?

Science and medicine march forward at an unnervingly slow pace, and we wait, holding our breath, having few other options.

Patricia Calderon

Patti was my best friend from age 12 on. Sex-crazed boys at the Turkish synagogue where we hung out on Saturday afternoons teased her mercilessly for her large breasts. She wore high-neck t-shirts and sweaters, careful never to show cleavage until she was nearly a middle-aged woman. She refused to hide behind frumpy blouses like the other girls with unseasonably large breasts. Behind her back, the boys came up with a long list of breast terminology—twins, tits, sisters, headlights, hooters, coconuts, casabas, cantaloupes, boulders, berthas, melons, and knockers—while they made smacking sounds with their mouths and squeezing gestures with their hands. “Vavavavooom!” They’d explode when Patti or another amply developed girl came into view.

Who knew then what her future would hold?

Offerings

On the same day that my younger son, Shiah, was born, my friend Bobbie’s sister, Tina, died of breast cancer. Tina had offered up both breasts to the stainless-steel surgical altar a few years earlier to no avail.

At three-days old, Shiah was the color of a watery-yellow bruise. He was diagnosed with severe jaundice, which required another hospital stay for treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit. While he was laid out like a plant in a light box until his bilirubin count dropped to a normal level, he drank far less milk than I produced.

I pumped my breasts every few hours, placed the bottles of milk in the pockets of a flimsy hospital robe, and smuggled the liquid gold into the maternity ward where I skirted around the nurses on my way to visit my friend Johanna who had just given birth to her fifth child. Smiling, I pulled out my still-warm milk and offered it to her. Johanna had had a bi-lateral mastectomy, both breasts removed, four years earlier during pregnancy. Her third son was delivered early a few months later, so Johanna could undergo aggressive treatment for aggressive breast cancer.

Five days after Shiah was born, Patti’s mom called. Patti, of large-breasted fame, at age 42, was on her deathbed in Manhattan. She had been diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer in her late 30s. Her medical team had urged her to have a complete mastectomy. She had opted to have one breast removed and take her chances.

A few days later, Patti’s mom called. Patti had died. I was sitting cross-legged on the couch, nursing Shiah, talking to my in-laws and my husband. Noah was next to me, his shirt flipped-up while he nursed his doll named Baby. I shook and sobbed uncontrollably. I wiped my nose with my sleeve and tried to pass Shiah to Steve, but Shiah was clamped to my nipple, not yet finished with his afternoon tea.

Who Knew that We knew?

Rachel Carson began writing Silent Spring, her epic environmental book, in the late 1950s. It traced the path of the chemical agent DDT through the food chain to humans via land, air, and water. She concluded that DDT was causing cancer and genetic damage. Her book was serialized in the New Yorker in 1962, a year after I was born, two years after Patti was born. Initially, no one was interested in Carson’s work despite the fact that she was a highly respected author. Her ideas were so out of line with the prevailing knowledge that they were dismissed as if Carson had lost her way, if not her mind.

Shortly after Silent Spring came out, Monsanto, the multinational agriculture biotech corporation, and the producer of the herbicide Roundup, published a parody of Silent Spring called Desolate Winter, which aimed to discredit Carson’s work. Monsanto asked what would happen in a world where bugs, famine, and disease ran amok because of the elimination of DDT and other pesticides. Did anyone in the Press question Monsanto’s motives? Where were all of the other scientists who knew better? Was there other conflicting research that was hidden or stifled? Did money change hands? Was the threat of cancer so little known back then that it didn’t ring any alarms? How many times has the same scenario unfolded since then? How many dissenters, like latter-day prophets, have tried to get our attention and failed? Rachel Carson died at age 57 in 1964 after a long battle with breast cancer.

From 1960 to 2003, the rate of breast cancer rose 181%. According to a 1993 study by the National Cancer Institute, “breast cancer is strongly associated with DDE (a form of DDT) in the blood.” In the early 70s, DDT was banned in the US; decades later, traces are still found in the environment, the bloodstream, and breast milk.

Because of the many changes that must occur to make healthy cells cancerous, breast cancer can take up to 30 years to develop. Why did it take science decades to conclude what Carson knew in the early 60s? Who knew that we knew so much back then?

My personal list of breast cancer tolls and loses rolls continuously like credits at the end of a movie. My mother-in-law had ductal carcinoma in situ a few years after Shiah was born. In April 2007, two friends, Anna and Little C, were diagnosed with breast cancer. Three more breasts removed. In 2008, my friend Sarah got a call after her mammogram. She had calcification sites. A biopsy followed. Thank God no breast cancer, but because she has dense breast tissue, she will likely repeat this cycle many more times. In 2011, my friend Em was diagnosed with HER2, an aggressive form of breast cancer. Soon after it was my friend Ren. Now, my dear friend Gee is recovering from a lumpectomy. My friend Maggie is waiting for the results from her surgical biopsy after having 2 mammograms, an ultrasound, an MRI, a needle biopsy and then the surgical biopsy. She waits. We wait.

Consciously and unconsciously, I recite the Hebrew phrase from my childhood, b’li ayin hora, literally translated as “without an evil eye,” an incantation that I use to protect my two small breasts and all breasts. I know far too many women whose shirts lie against flat chests, dented chests, foam, silicon, or saline. I wonder who declared this war on women.

No Matter what You Call It

Four years ago, Jules, one of my favorite students, came to a yoga class I was teaching for cancer patients, survivors and their caregivers. She wore a pin that said, “Not yet dead,” from Monty Python’s show Spamalot, which she had seen in Las Vegas with a group of women who were living with metastasized breast cancer.

Many of my students have or have had breast cancer. The stages and diagnostic names sound industrial and mechanical, as if named by an engineer in a steel plant: ductal carcinomas in situ, lobular carcinomas in situ, Paget’s disease, ductal and lobular carcinomas, inflammatory breast cancer, angiosarcoma and cystosarcoma phyllodes, estrogen-negative cancers and triple-negative cancers. Breast cancer, the catchall phrase, oversimplifies the highly variable disease, the treatment options, the side-effects, the variety of outcomes and chances for survival, recovery, and recurrence.

Jules has lived with metastasized breast disease for ten years. In 1999, she was diagnosed with Stage 2, a diagnosis that she thought meant she’d be fine after treatment, but it didn’t work out that way. Three years later, she had a sore leg, which felt like a pulled muscle. An x-ray showed extensive bone metastases in both of her femurs. An MRI revealed she had metastases in her skull.

When Jules arrived to class with her Monty Python pin, we wanted to laugh and cry in the same moment. Jules spoke our fears when she said, “I sometimes wonder when the other shoe will drop.”

Reaping and Sowing

Washington State is known for apples, asparagus, airplanes, wheat, timber, coffee, computer genius, marijuana, and BREAST CANCER. According to the Center for Disease Control, women in Washington State (me) have the highest rate of breast cancer in the nation. Typically, we delay childbearing (me) or skip having children altogether. We drink more alcohol (not me). We absorb less vitamin D due to lack of sunshine, and more of us use hormone replacement therapy to beat back the effects of menopause—all of these factors are known or thought to increase the risk of breast cancer.

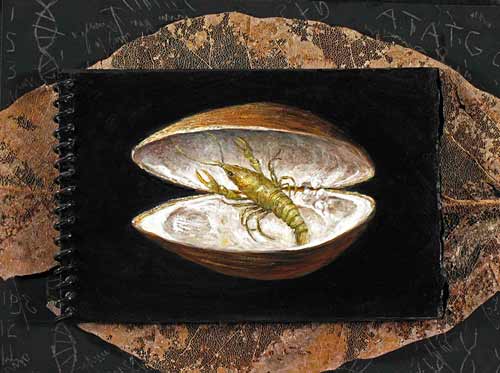

Ashkenazic (Eastern European) Jewish women (me) have a higher rate of breast cancer than the general population. Five to ten percent of all women with breast cancer have a gene-line mutation gene. The genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 when normal and healthy protect breast and ovarian cells by being tumor suppressors and ensuring genomic integrity. Genes, made up of thousands of DNA letters that run down the DNA double helix, can become delinquent, dangerous, and deadly with the deletion of a single DNA letter.

Long, long ago, when Jews were called Hebrews and wandered in tribes through ancient Israel, DNA letter 185delAG was accidentally dropped; but unlike a stitch in knitting, we’ve not been able to pick it up, and it’s been a deadly error. Translation: Women with the BRCA1or BRCA2 gene have up to an 82-percent chance of developing breast cancer by the age of 70.

A few months ago, I went to the doctor for a sinus infection, and for a dreaded round of antibiotics. My doctor rifled through my chart as though looking for something she had lost.

“I don’t see your last mammogram here.”

“I had one last year with my annual.”

She turned a few more pages and said, “You haven’t had one since two thousand and eight.”

“Shit! Are you sure?” I was stunned. How could I of all people have missed even a single mammogram? I looked at my doctor thinking she had misread my chart.

“Really” I asked again.

She nodded. “Really, two thousand and eight.”

Women and some men will continue to be diagnosed with breast cancer each and every day and each and every year. I see breast cancer in part as a collective karmic return for environmental misuse, arrogance, lack of awareness, and greed, but it’s also an opportunity for change. As we pollute and defile our world or watch others do it, and pass it off as an unavoidable complication of modern life, we suffer and rack up negative karma. Karma is the cause and result of our actions. Think of it as a self-perpetuating loop that can be stopped if we take action. To believe that things have to be the way they are, to believe that we have no choice, to believe that we are stuck with what we have, is to live without hope.

Stacy Lawson is a yoga instructor and writer living in Seattle with her husband, two sons, and dog. She is the founder of Red Square Yoga, a by-donation studio focusing on therapeutic yoga. Stacy’s work has appeared in Under the Sun, Drash Northwest Mosaic, The Seattle Star, and Sunday Ink: Works by the Uptown Writers.