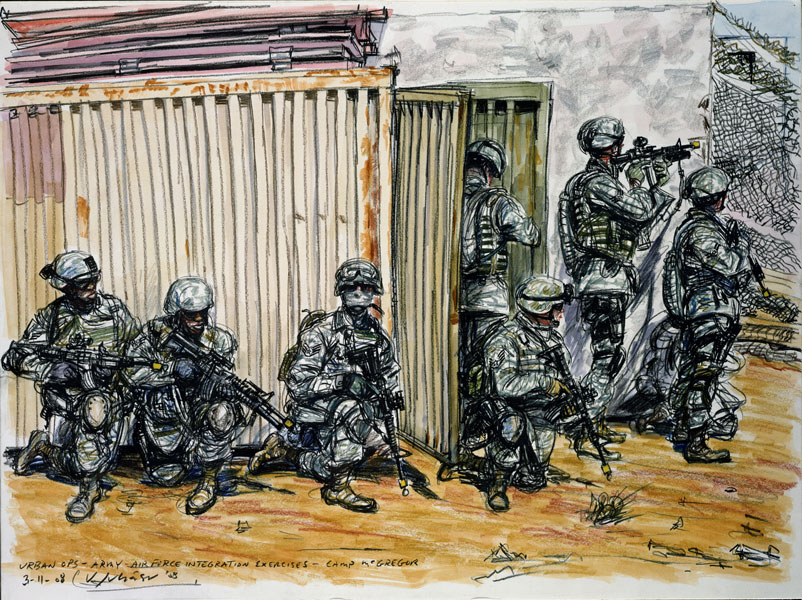

Image courtesy USAF Art Program, Victor Juhasz, artist

Walberg punched a fist into his open palm and said, “I’m going to hit you so hard, Rudy, you’ll be too fucking numb to feel anybody else.”

He sat atop the workbench that ran the width of our workshop aboard the USS Proteus, his legs hung over, boot heels kicked into the sliding doors below. He was a tall, skinny guy from Long Island who always carried a copy of Mother Earth News folded in his back pocket and a pack of Winston menthols tucked into his sock.

Craig, a doughy Midwestern kid with big ears and Navy-issue glasses, leaned against the workbench and laughed at Walberg’s threat. He was Walberg’s best audience.

“Fuck that,” EM1 Wallace said with a condescending nod. He was leaning against the electrical switchboard. EM1 was my boss, the first black man I’d ever worked for. He looked more like a linebacker or a prison guard than a First Class electrician’s mate. He paused to scratch his chest then said, “You got a better chance of banging Madonna than you got of punching him harder than me.”

We were hanging out in the Sparky shop between knockoff and the dinner whistle aboard the Old Pro. This usually entailed a couple of us shooting the shit and generally dicking the dog. We were at sea. It was our first day out in more than six months. It was also the eve of a promotion for which I was long overdue.

Anyone aboard, E-4 and above, was allowed to punch me once. Tacking on my chevron. For most sailors, it was largely ceremonial. A right of passage like fraternities in college. But there were others in it for the sport. I couldn’t blame them. There aren’t that many opportunities to hit someone, completely without repercussions or reprisals.

I’ve heard stories about guys who couldn’t raise their arms above their heads for two weeks and a couple urban legends where blood clots set in and killed the newly promoted guys in their sleep. I didn’t really believe that shit. From what I understood, the more people liked you, the harder they hit you, to earn your respect.

Craig said, “You better pull out the needle and thread. You’ll be Betsy Fucking Ross for the next couple days sewing on your chevrons.”

“Don’t go spending that extra money right away,” Walberg said. “They can take up to a year to start paying.”

The jump in rank promised $160 more per month. I didn’t have a wife and kids, but I was responsible for a family back home.

~

Whenever a new guy arrived, the squid assigned as his Ship Sponsor would ask, “How long’s your sentence?” No matter the reply, the Ship Sponsor always said, “It’ll seem longer.”

Most of my shipmates considered it a prison sentence, being stationed aboard the Old Pro. The ship was homeported in Apra Harbor, Guam, and we called it “the rock” because of its similarities to Alcatraz. The compressed land mass seemed to shrink daily; escape was virtually impossible, even when out at sea because they always had to come back to homeport. These squids referred to their massive ship as “the yard” because it was a cluster-fuck of iron and steel stretching the length of two football fields. They called the Chiefs “Hacks” as if they were prison guards. Captain was their Warden.

What the others considered imprisonment was freedom to me.

~

The shop was cold from the freestanding, five-ton AC unit that sat along the far wall. It offset the heat put out by the switchboard and the transformers for the GYRO navigation equipment up on the bridge.

Walberg hopped down from the workbench and walked toward EM1. He slung his arm up, but his reach was only halfway across the man’s broad shoulders. “Okay,” Walberg said. “I’ll admit that Rude’ll be crippled when you hit him, but please let me hit him first so he feels us both.”

Hixon sat on an overturned garbage can. He had been quiet, which wasn’t like him. When he had too many Mountain Dews, he was like one of those dogs that jump on everyone as they enter the house. This was his first cruise and I didn’t know if his change in demeanor was from seasickness or if he was just all fucked up over having to leave homeport. Neither made sense because he wasn’t missing anything back on Guam and so far, the seas had been smaller than some waves I’ve made in the toilet.

“At this pace,” Hixon spoke up, “you’re on pace to retire an E-5.”

Craig and Walberg said, “Ooh,” in unison.

EM1 looked at Hixon, said, “Damn,” and lowered his hand from the switchboard to cover his mouth.

My promotion was overdue because I’d gotten in a little trouble: once for missing a one-day ships movement because a Korean chick’s alarm clock didn’t go off, and once because I drank too much and got caught urinating publicly, on sacred Japanese land in Sasebo. I had also failed the Third Class Electrician’s Mate test twice. I knew my job. My performance evals listed me as a solid journeyman electrician, but even in school I was never good at paper tests. Ask me a question and I can tell you the perfect answer. Put me on a job and I’ll get it right the first time. But seeing the multiple choice answers in black and white, even at twenty-three years old, made them all look the same. I was still stunned that I’d guessed correctly enough times to finally pass.

Hixon said, “You’re as old as a canker sore at a nursing home.”

Coming from EM1 that would have been funny because he was older than me. Coming from Craig, it would have been funny because he was younger than me. But Hixon was my age and has held that rank for almost a year. He smiled his unhappy Tennessee smile.

This was my fourth cruise in almost as many years, but I was the lowest man on the totem pole in our workshop. All the others treated me as an equal. Hixon was the only one who showed me no respect. Fucker. While I was sweating it out in the fleet, he was sitting pretty in some fancy “C” school in Chicago. The difference meant something to squids like me. My uniforms had the grease and bloodstains while his were new and starched and loose around his arms and neck.

One more day and he wouldn’t be able to tell me what to do any more.

I said, “Shut up, Hixon. You’re as useful as a deck of cards at an orgy.”

He pulled out a modest wad of cash.

“Where’d you get all that money, Hixon?” EM1 said.

“Since we’re at sea, I’m saving money by jerking myself off.”

“I bet you are, fucking pud puller,” I said.

Stuffing the cash back into his pocket, Hixon said, “But tell your mother I’ll make it up to her when we get back.”

I pointed and said, “Don’t talk shit about my mother , asshole.” I hated the sonofabitch and for all I knew he hated me, too.

Hixon reached his hand out, slowly, almost playfully, toward my face. I didn’t feel threatened, didn’t move. In the next instant, his hand touched my face and he pushed me away, like a stiff-armed running back.

I heard noises in my head like tree branches or wooden boards cracking. My throat burned and my mouth grew pasty. I exploded with as quick a punch as I’d ever thrown.

The punch didn’t land as squarely as I would have liked, but my third and fourth knuckles throbbed instantly. The blood that streamed from Petty Officer Hixon’s nose surprised me.

He back-pedaled, bent at the waist, his arms out wide, hands shaking like a woman with wet finger nails. For a second I thought he was going to cry. Blood poured from his face. He reached up with shaking hands and smeared his cheeks. “My nose,” he said without inflection. An instant later, he called out, “Mercy be.” He doubled over, dripped blood onto the blue electrical safety mats with the faded USS Proteus pie-shaped emblem: “Prepared, Productive, Precise.”

“Pinch that snot blower of yours and lean your fucking head back,” EM1 said folding his arms across his chest.

By the time Hixon complied, a puddle had formed at his feet.

Hixon looked up at me. A stream of snot ran from his swelling nose. There was blood in the snot that hung from his right nostril. None of us spoke for a minute. The 400-Hertz generators hummed on the opposite side of a watertight door.

I stuffed my hands into my pockets and said, “No. Shit no. I didn’t just do that.”

EM1 said, “Well if he ain’t going to hit you back, you better get him up to sick bay right quick. That nose is fucked. And get back here to clean this shit up.” He pointed at the puddle.

Our shop was below the waterline. Sickbay was six decks up. “How am I going to get him there without anyone seeing us?” I asked.

“You’re probably not.” EM1 said. “But on the way, ask him real nice if he’ll tell Doc that he fell.”

~

Hixon’s mouth was moving. The sounds he was making weren’t words, exactly. Not yet. They soon would be, I figured.

He whimpered and stopped at the hatch as if he couldn’t go on. I’d been busted in the nose plenty of times. Had my jaw broken after senior prom. Spent the remainder of the school year, and graduation, sipping shakes and beer through a straw because of it.

I was going to get locked up in the brig. The ship’s brig, “Hell” as all aboard called it, sat in the bowels of the ship. It had four cells with iron bars and was run by Chief Master at Arms Halsey, a fire hydrant of a man who once ran PT boats in Vietnam. He was thick with muscle, head shaved clean, with a heavy Louisiana accent. He sported the scales of justice tattooed on one forearm and a guillotine on the other and he squinted as if he perpetually had smoke in his eyes.

In the vestibule outside the shop, the rich and meaty smell of Sloppy Joes was as dense as a fart in the berthing compartment. It filled the passageway. It was dinnertime and most of the crew was on the mess decks for chow.

At the ladder, Hixon balanced his hand under the yellow stream jetting from his nose. I didn’t know if this was because he didn’t want to soil the deck or if he wanted to save it as a souvenir. “What the hell is that disgusting thing, anyway?”

“I don’t know,” he said, he held his fingers against his cheekbones as he angled his head down to see the first step. “But I fear it’s not a good sign.”

“Let’s go,” I said and tugged on his arm. The sleeve of his work shirt tore a little, the seam popping at the shoulder.

“You’ll have to help me,” he said.

I could have kicked him in the face. “Hang on,” I said, and took him by the arm.

He moaned as we took the next step. The groan came out low and guttural, so feeble that I wanted to laugh. “Quit your bellyaching,” I said. “I didn’t punch you in the legs.”

“I’ve never been punched in the nose before!” he said, still pinching the bridge of his nose.

“How can that be possible?” I half-dragged him up the ladder. “There must have been lines formed to do that since you was a kid.”

“I’ve never been in a fight before.”

All I saw when I looked down at him was the delicate white fingers he used to pinch the bridge of his nose and the yellow thing still dangling. I’d seen him in berthing every day for six months. He took off his t-shirt by slipping out the arms first and then pulling it over his head. The only guys I knew that did that were raised by single mothers.

His hands were small. They reminded me of my sisters.

The other day, over the phone from a half-booth on the pier, I told my mother I’d be sending home extra money. “Why?” she asked. “You gambling again?”

“No ma’am,” I said. “Because I’m advancing a payscale. I’m making 3rd Class.”

“It’s about time,” she said. “Your sister’s in rehab again. That shit cost money.”

I wasn’t allowed to backtalk. Back home I wasn’t allowed to be rude, to anyone. The town I grew up in was the two-stoplight variety with only one school, one store, and two thousand staring eyes. But after a couple years stationed aboard the Old Pro, I’d transformed myself into Rudy. I’d bulked up twenty pounds. I kept my hair short and a moustache a millimeter within regulation.

I’d joined the Navy for the steady paycheck, but also to get away from my mother and sister. I hated them both because my sister was the light in my mother’s eyes and that girl was never anything but trouble. She used to put pots and pans over my head and beat them with wooden spoons or spatulas. She was eight years older and mean as hell well before she found her way to speed and cocaine.

~

By the time I got Hixon to the next ladder, I expected the yellow thing to drop like an icicle from his nose, but it didn’t. His face was whiter now than his hairy knuckles. This is when I knew it wasn’t just snot dangling there.

A gust of wind blew the watertight door back into me as I opened it to the main deck. It took a good push to get it open while holding up Hixon with one arm, pushing with the other. Air rushed us once we made it to the main deck replacing the food smells of the mess decks with diesel fumes. Waves broke large enough to elevate spray that darkened our chambray work shirts. The last time I’d been topside, all conditions were calm.

Air on the main deck of the ship was different than it was below. It was easy to forget how bright sunlight actually was when you didn’t see it for a couple days. Being on the main deck, we were halfway to sick bay and I had to squint in order to see. The Boatswains moved in the sunlight – they gleamed like ghosts. Little bursts of sunlight glittered off their heads. Gulls cried overhead. One of the Boatswains reared back and spit over the side and dropped to do pushups on the deck.

“I don’t feel so good,” Hixon said, grabbing the life rail and collapsing his weight onto a mooring bollard. His voice was pitched higher now. “But thanks for helping me.”

“Helping you?” I said.

“I know,” he said, lowering his head between his knees as if to stop nausea. “You were ordered to.”

“If it wasn’t for me, you wouldn’t need to go to sick bay.”

“But orders are orders,” he said, pulling his head up, resting his elbows on his knees. “And they’re what’s really important.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

Hixon said, “What if we crossed paths out here with a Russian Destroyer? What if they launched on us? What do you suppose Reagan would do?”

I’d seen the movie “Patton” when I was a kid. In it, George C. Scott had said something about fighting the Russians right then because if they didn’t, we’d have to eventually. “He’d vaporize as much of the USSR as he could.”

“Exactly. And what if we fired on that ship first?”

“I reckon they’d vaporize the US. That’s why we always had them drills in school.”

“Exactly my point. All those drills. All the drills we’re forced to do on this ship. Do you think they’re just to kill time? If the Russians send a plane, we could be torpedoed in an instant. They got this fucking bird, the KA-27 Helix with counter-rotating triple-blade rotors. Those fuckers are anti-surface and anti-sub. Torpedoes and depth charges. They could search and destroy us on both fronts. They could be looking for a hot nuke and we could end up collateral damage.”

“You’re exaggerating,” I said.

“They’ve got Kirov cruisers that’ll do 40 knots. They got vertical launch missiles and anti-surface shit you can’t imagine.”

“They’re not going to use that shit against us. Nobody wants World War III.”

Hixon leaned forward, letting that yellow thing dangle. “Just in case, I’d rather have shipmates that didn’t hate me. If any shit goes down, hard feelings might make us react on attitude instead of our training. We can’t risk that.”

“If anything goes down tonight, I’ll be in the brig and no help to anyone.”

“I won’t say anything,” Hixon said. “I fell into the switchboard. Hit the switch for the 400s. That big nasty red one. That’ll work.”

“You’re fucking with me now.”

“I’m not. Seriously.” He looked up at me. “I won’t talk.”

“Why would you do that?”

“You’re my shipmate.”

“Don’t fuck with me, Hixon. If you’re going to be a dick, just rat me out. I don’t care.” I stopped for a minute and looked over the railing at the water breaking white at about four feet. “I suppose you want me to stand your watch or take your duty once a week for the entire cruise.”

“And make my rack every day…”

I wanted to punch him again.

“How about I do your laundry, too?” I said. “And buy you sodas.”

“Now you’re talking,” Hixon said, pushing himself to stand.

“Anything else?”

“I’m just fucking with you. I don’t want that stuff. All I want is you to hang around with me at chow and go with me on liberty.”

“That yellow thing dangling there must be part of your brains.”

“You might be right, Rudy. You agree to the terms?”

“And I don’t have to do none of that other shit?”

“Nope. That’s it.”

“Fine,” I said, though I would have rather been his servant than his friend.

Hixon held out his hand. I gripped his delicate fingers and he winced, trying to pull his hand away. I squeezed as if it could choke him.

~

The Boatswain’s mates packed it in for the day; their grinders quiet, their chipping hammers still. Most of the crew was at chow and it was quiet on deck. I turned around and grabbed the life rail in my hands, squeezing until my knuckles cracked. Suddenly the oppression the others had felt aboard the Old Pro overtook me. This salty bucket of shit was now my prison, too.

Befriending Hixon was a one-way ticket to alienation and unspecified rations of shit. The idea of having to break bread with him every meal repulsed me to the point that I feared a dramatic and deadly weight loss. And I knew immediately how impossible it would be to pick up women with him as a wingman. Unless he paid for a working girl, there was no chance. I’d never paid for it in my life and I wasn’t about to start now. And I sure as hell wasn’t going to go the whole cruise without getting any.

With every remaining ounce of energy I yelled, “Come and get me, you filthy fucking Ruskies.” I yelled more and louder expletives. “We’ll kick your fucking asses all the way back to Siberia.”

There were no ships visible on the horizon. Nothing but water.

I got Hixon up. The dangling yellow thing swayed as he got to his feet. I could have puked. “Hey,” I said.

Hixon’s head swiveled slowly, the dangling yellow thing moved with him.

“Either pinch that thing off or snort it back into your fucking head. It’s making me sick.”

Once inside Sick Bay, the chief corpsman looked up from his crossword puzzle. My vocal chords were raw from the abrasive salt air as I said, “Doc, call Master at Arms Halsey” and then told both of them the truth.

Jeffery Hess is the editor of Home of the Brave: Stories in Uniform, an anthology of military-related fiction. He holds an MFA in creative writing from Queens University of Charlotte and his writing has appeared in numerous corporate publications and websites, as well as in r.kv.r.y, Prime Number Magazine, The MacGuffin, Plots with Guns, The Houston Literary Review, the<em > Tampa Tribune, and Writer’s Journal. He lives in Florida where he leads a creative writing workshop for military veterans and is completing a novel.

Read an interview with Jeff Hess here.

“Last Battle Aboard the Old Pro” first appeared in The MacGuffin in slightly different form.