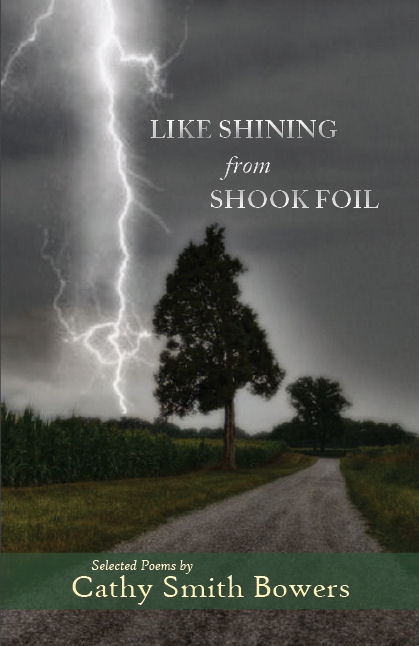

Image by Kristin Beeler

Steam rises. My clothes begin to freeze. Those damned coin-operated dryers at the dormitory never do the job.

I save quarters for cigarettes and dollars for beer and never have enough for more than one dryer cycle. Soon I’m frozen solid as the Tin Man. Other students, well bundled for the downhill walk to class, don’t notice.

Dormitories of brick stand silent and brown. The river is choked with ice and the ice is piled with snow. Trees stand naked and the sun sleeps, buried by clouds. Boots whisper over the snow and words turn to smoke. The white wall of the campus chapel is defaced by the black, spray-painted words of Nietzsche: God is Dead.

Am I dead, too?

In developmental psychology class, I begin to thaw. Twenty minutes into the lecture, I might have just climbed out of a swimming pool. But nobody looks. Not even when a small puddle forms beneath the hems of my jeans. My sleeves drip onto my blank notebook. Even the little, gray-haired professor, who has no choice but to look, doesn’t.

A woman in a denim jacket palms me a menthol. I hate menthols, but beggars can’t be choosers. As pathetic as this looks, bumming isn’t as bad as digging through ashtrays in the dormitory. And I’ve wandered the student union so long that my clothes are nearly dry. Ten more cigarettes and my empty pack will be full again.

A few more empty beer cans from the wastebaskets in the dormitory and I’ll skip my afternoon philosophy class and carry them to the recycling machine on Water Street. This benevolent, cast-iron monster spits quarters. I hope it spits enough for me to buy a twelve-pack of cheap, local beer—but even twelve beers don’t get me drunk enough. Not anymore.

I’ll have to use my knife.

It’s a bread knife, serrated, bent and blunt, but not too blunt to cut a hole in a can of beer. Warm beer works best. It’s easier to swallow. So I split my stash in half: six cans for the refrigerator and six for the ledge. Then I set the first can at an angle on my writing desk, prop the bottom of it with a psychology book, drive the crooked knife through the aluminum, fold back the sharp edges, seal the hole with my mouth as I lift the can and pop the top.

Five seconds and the beer is gone.

I shove the can under my desk like I shoved empty vodka bottles under my bed before I went away to college, where I planned to quit drinking— right after my 20th birthday.

When I’m drinking, my roommate stays away.

Popping another beer open, I feel a good buzz start. After “shooting” three more I can relax and drink the cold ones that I crammed into my roommate’s little refrigerator in place of his sodas.

Finally, I’m a little drunk. Only two cans remain from the twelve-pack. The news starts. Outside, far beyond the women’s residence hall, red lights flash from a radio tower. Red…. Black…. Red…. Black…. Red…. Black….

The beer is gone. I feel dull all over. This knife is dull, too. I press harder, running the serrated blade across my palm. The stinging sensation isn’t mine—I’m simply aware it is there. I press harder…. The blood is mine. I use it to write on the blue wall of the dormitory room using the words of the Beatles: “HELTER SKELTER.”

I wonder if anyone will notice.

Craig Boyer started writing in the mid-1980s by recording his nightmares and sharing them with Dr. J. Allan Hobson of Harvard, one of the world’s foremost dream researchers. Since that time he has published essays in Blueline, Breakaway Books, Nostalgia Press, and The Bellevue Literary Review, where in 2005 he published The Devil and a Pocketful of Glass about his lifelong struggle with obsessive-compulsive disorder. In 2003 he was admitted to the MFA program at the University of Iowa, but chose instead to keep his full-time job and start a family. He now works as a behavioral specialist with Emotionally/Behaviorally Disturbed high-school students and has a beautiful wife (Liz) and two beautiful children: (Ellie-6 and Alex-2). 1984 is an excerpt from his memoir-in-progress, Deja Vu: snapshots from the journey of an obsessive-compulsive. Visit his website at: Deja Vu

Read our interview with Craig here.