Andrew Stancek: Len, your essay “Jury Duty” in the current issue of r.kv.r.y immediately gripped me. I admire your fiction but this was my first opportunity to admire your non-fiction as well. I love the tone, the vivid characterization, the narrative drive. As a fiction writer I see events unfolding around me as prompts for fiction. Why did you decide to fashion an essay out of this material, rather than a story? For me the atmosphere is crackling with writing prompts, each calling out for a treatment, and my role is that of a shaper. How do you approach writing and what do you see your role to be?

Len Joy: The piece that ended up being “Jury Duty” I originally wrote with the idea I would use it in my blog, Do Not Go Gentle… .I started the blog just before I turned sixty, to chronicle the challenges of trying to become a writer and an age-group competitive triathlete at what I guess could be called an advanced age. Or old. Not young anyway.

I try to keep the blog pieces short (under 300 words) and this story ended up being much longer so I decided to find a more appropriate home for it. I was thrilled to have it published in r.kv.r.y. (although I still struggle to spell it correctly).

For fifteen years my brother-in-law and I owned and operated an engine remanufacturing

company with factories in Arizona and Missouri. We wound the business down in 2004 and that was when I took my first writing course. The company was not a huge financial success – it was a struggle from beginning to end – but it has provided a wealth of writing material.

The first short stories I attempted to write were just fictionalized accounts of things that we

experienced in that business. They were not good stories, because, as I eventually learned, life isn’t a novel. It’s messier and it often doesn’t come to a nice neat ending. Oh. And too much happens in real life, some of it not that interesting.

It took me awhile to grasp that writing fiction meant I could cut out characters and scenes and rearrange stuff and just make up a lot of shit. It was very liberating. In my novel, “American Jukebox,” which will be published this year (yay!), I have several chapters that take place in a factory. I’ve drawn on my work experiences to make that experience feel authentic. (I hope).

I like writing both fiction and non-fiction. If I were, say, forty, or younger, I would have a

different approach. I think I might try to write more non-fiction – I see a lot of interesting stuff related to triathlon competitions and the people who are pursuing those events. But I have to be realistic – I started writing late in life and I probably won’t live forever, so my plan is to focus on fiction.

Andrew Stancek: This certainly resonates with me. Sixty is close to the horizon for me and I, too, have started writing late and recently, reluctantly, I have begun to realize I probably won’t live forever and I’d better prioritize. (Laughs.)

Let me briefly continue to pursue this idea of artistic genesis. I am forever fascinated by how and why a writer chooses to write a particular piece. I return time and time again to Faulkner, who famously said that The Sound and the Fury began for him as an image of Caddy’s muddy drawers seen from below as she clambers up the tree outside the Compson house in order to see what is happening. Can you speak generally about the origins of some of your short stories and of this particular essay? Is it an image that begins the process for you, a character, a line of dialog imagined or overheard, a theme….?

Len Joy: I think that usually the initial inspiration for a story will be some scene or event I

witness or imagine. For instance, I wrote a story a few years back called, “My Father’s Ice,” which was inspired by a trip I made to the Whitney Museum with my wife. We toured an exhibit of a somewhat obscure performance artist of the 1970s named Gordon Matta-Clark.

As is usual when we go to museums, I finished the walk-through in about a half hour and my wife took well over an hour. While I was waiting for her, I imagined a story about someone who might have left school to go to work with this artist. And then I thought, what if his daughter discovered him 30 years later, captured on one of the videos that were part of the exhibit. So for that story I had an interesting experience/event and then I created a character. I can’t go anywhere with a story until I have a character. For me the stories are always about the people.

In the “Jury Duty” essay, I noticed a young woman who was having difficulty dealing with the coffee machine in the juror’s waiting room. Later I encountered her in the cafeteria where she didn’t have enough money for the food she had purchased. And then in the afternoon, when we went to jury selection she was unable to answer the basic questions the judge asked her about her previous experience. At the end of the day, she was selected for the jury and I was sent home.

The novel I have been writing for the last four years was originally inspired when I was driving back from the Iowa Writers Festival at the University of Iowa. I was headed to Chicago and there was a huge traffic jam in the opposite direction for those cars headed toward Iowa. I passed miles and miles of cars going nowhere. A few minutes after I had driven beyond the traffic jam I saw a guy in a convertible racing along, not a care in the world. He didn’t know that in a few minutes he was going to be stuck in that traffic jam for the next several hours.

The name Clayton Stonemason just popped into my head. I decided he was sort of a screw-up and that he was headed to the wedding of his niece. And he was supposed to give a toast. I wrote a short story from that scene and from that story I ended up writing the novel. As it turns out the whole novel takes place years before this incident and so that story is not even in the novel. But it got me started. From that one traffic jam I created a whole fictional world.

Andrew Stancek: I have had the good fortune to study writing with a number of wonderful teachers and hope to study with a great many more. Have you taken workshops or courses with teachers you’d recommend? In an ideal world, if you could study with anyone in the world, who would it be? Are there writers who have influenced you?

Len Joy I think one of the areas where athletic pursuits like triathlons have some similarities to the writing profession is in the area of training. Even if you have an abundance of natural athletic talent it is difficult to become proficient at something like swimming without training.

Because I didn’t come to the writing field until later in life, I decided it wouldn’t be a

particularly good use of my time or money to pursue an MFA. However I knew that if I wanted to improve I would need some kind of professional training.

I took a sequence of writing courses at the University of Chicago’s Graham School. The

introductory courses with Barbara Croft (“Moon’s Crossing) and Eileen Favorite (“The

Heroines”) were excellent. Both writers provided me with a solid base in the fundamentals while offering reasonable encouragement. I took a sequence of novel writing courses there which were taught by Patrick Somerville (“The Cradle,” “The Bright River”). He was an excellent teacher, very generous with his time and his advice was always practical. He was a compassionate critiquer, but didn’t hesitate to point out when something didn’t work.

In addition to the Graham School, I have tried to go to a summer workshop program every

year, which I look at as summer camp for adults. For several summers I attended the Iowa

Writers Festival in Iowa City. I thoroughly enjoyed the wide variety of craft-based workshops they offered. The first instructor I had there was Sands Hall, (“Catching Heaven”). She too, stressed fundamentals such as point of view, when to show and when to tell, and probably most important, making sure that your story maintains a “sense of place.” Don’t let the reader get lost.

In our one on one conference when I expressed some concern that my writing seemed sort of thin (what I meant to say was that it didn’t seem very “writerly”), Sands assured me that my voice and writing style were fine and that I should check out Raymond Carver. I thought she meant Raymond Chandler, but once I got on board I read everything he wrote and that probably has been an important influence on me.

Because of Sands Hall, I attended Squaw Valley for two years (her family runs that workshop). That was also a great experience in a beautiful location and because in their workshop, the leaders rotate every day, I got to meet agents, editors and publishers, as well as writers. That experienced really helped me to better see the breadth of the publishing industry.

Three years ago I went to the New York State Summer Institute at Skidmore. My workshop

leader was Joe O’Neill (“Netherland”). He shared with us some of the techniques he used for shaping his novel through the revision process. He would go through text with colored markers identifying certain themes. Then with that visual aid he would rewrite to emphasize or de-emphasize important themes and symbols.

A couple years ago I made it into Sewanee. I wasn’t sure if I would like the caste system where half the workshop is Fellows or some other grand poobah designation and the rest of us are just plebes. But in reality that was not an issue. I was very impressed by the skill level of the attendees – many of the writers in my workshop had already published novels and collections.

My workshop was run by John Casey and Christine Schutt. They made a great team and both of them are older than me, which was a nice change of pace. They had a great sense of perspective and humor, which is helpful because some of those poobahs can be pretty harsh in their critiques. It gave me an inkling of what an MFA program would be like and it reaffirmed for me the wisdom of not going in that direction.

I recently had a chance to read a Ray Carver story in its original draft and then the version that was marked up by Gordon Lish. It was, of course, Lish’s edited version which was ultimately published. I thought Lish’s editing was brilliant. And it was so educational to see all the words that weren’t needed to tell the story. I guess I am sort of a minimalist (notwithstanding these long-winded answers) and that editing skill impressed me.

So if I could study with anyone in the world it would be Gordon Lish.

As for writers who influence me, when I grow up I want to be Elmore Leonard. That might be because I’m a huge fan of the TV series “Justified,” which was inspired by Leonard’s novella, “Fire in the Hole.”

Andrew Stancek Len, I am fascinated by your reaction to the Lish editing of Carver, and then your admiration of Leonard. Lish’s editing has received a fair bit of criticism recently and there are those who feel he was much too intrusive and frequently just wrong in his editing. But of course it is his versions of Carver which we know and love. And one of the hallmarks of Elmore Leonard, whom I also admire enormously, is his spare style. So let’s bring this more directly to you, your style, your hopes and ambitions. Where do you hope to be in your writing in five, ten, twenty, pick a number years? Do you see yourself as a short story writer with stories in the New Yorker and Ploughshares and Tin House? A literary novelist? A popular bestselling novelist? A genre writer? What do you hope for?

Len Joy With respect to Carver and Lish, I guess what fascinated me was the opportunity to see the before and after texts. It is a great example – at least it was for me – as to how fewer words – can make something more powerful. I welcome editing. It is so easy to get stuck and not see that there might be a better path to the finish line.

I hope I am still writing in twenty years. The direction my writing “career” takes will depend on what happens with my novel. If the book achieves some measure of success (critical acceptance and/or decent sales) then I will most likely finish the sequel. I already I have a “draft” completed (I cut the timeframe of the original novel from 50 years to 20 years so I have all that excess material I can use). I enjoy the world I’ve created and it has a lot of potential so that’s a likely possibility. I also enjoy writing flash fiction and short stories. I will continue to work on both of those while also working on a novel (whether it is a sequel or something new). Most of all, I want to continue to improve as a writer and I really want to be read.

It would be nice to have readers willing to pay to read my stuff as that would be a tangible

measure of success. Plus, I like money. I don’t anticipate or count on huge financial rewards, but I could handle it, if it happened. I think my stories are commercially viable, so you never know.

Andrew Stancek: Can you comment on the illustration that appeared with your essay?

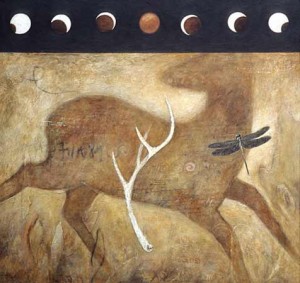

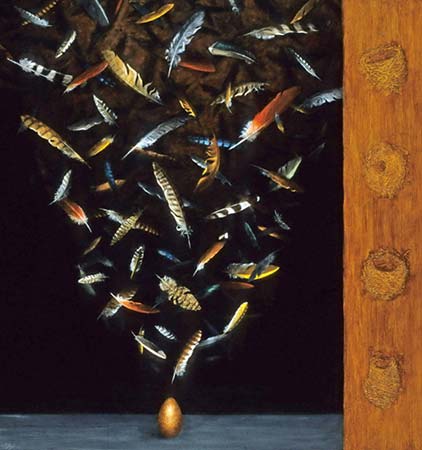

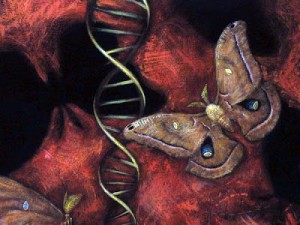

Len Joy: I really like the idea of having artwork “introduce” the story. And all of the artwork

provided by Suzanne Stryk for this issue of r.kv.r.y is very compelling. I think that the visual

aspect of reading is often overlooked by prose writers. Clearly, poems have a visual aspect – with stanzas and line breaks – but so does prose. I definitely have a different mindset when I am reading a page that is wall-to-wall words than when I’m reading a page with lots of white space.

Similarly, when I walk into a book store, I am immediately influenced by bookcovers. Even

if there is no picture or scene on the cover, the typeface, the color the font, all effect my initial attitude and/or expectation for the book.

With the stories in r.kv.r.y the artwork is the “cover.” There may not be a clear connection

apparent between the artwork and the story, but the art still influences how the reader approaches the story.

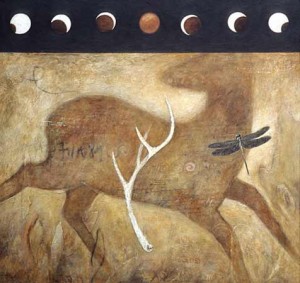

I really like the painting, “Eclipse,” which accompanies “Jury Duty.” I sense flight. Fear and

some sort of a controlled chaos. The disembodied antlers are enigmatic and intriguing. I think the emotions stirred by “Eclipse” are appropriate as an inducement and as a frame for someone who is about to read the essay.

Andrew Stancek: What does “recovery” mean to you? Are you recovered?

Len Joy: I am glad this question was asked and that I took some time to think about it. To me recovery means not giving up. It’s hard not to respond with clichés but I see it as staying in the ring after you get knocked down. Or maybe to stretch the metaphor, finding a new game to play.

As I mentioned earlier, for over fifteen years my brother-in-law and I operated an engine

remanufacturing company. It was a monumental challenge for someone who hadn’t grown up in that business, but I was convinced we would ultimately prevail. We did not. A lot of companies failed and, ultimately, we were one of them.

When I exited the business in 2004 I was financially strapped and had to deal with the realization that I was in some sense a failure. I decided that experience would only be the defining moment of my life if I allowed it to be. If I didn’t keep going. If I didn’t write another chapter.

I almost immediately developed another business opportunity and I pursued a writing career. The business I developed allowed me to restore my retirement plan and helped heal my bruised ego. But writing – producing something I was proud of that was good enough that other people would actually read it and enjoy it – that restored my spirit.

I’ve really enjoyed this interview. It’s made me think about what I’m doing. Sometimes we all get caught up in the process, so it’s nice to stop for a moment and reflect. Thank you, Andrew and Mary for the opportunity.