Mary Akers: Hi, Liz! Thanks for agreeing to talk with me today, and for letting us have your wonderful short story “Covered in Red Dirt.” I first read it in your kick-ass collection Baby’s on Fire and absolutely loved it. I feel a strong sense of longing when I read “Covered in Red Dirt,” and an additional sense of…for lack of a better word…unfinishedness…? And I don’t mean that the story feels unfinished—it doesn’t. I mean deliberately “unfinished” in the way of a beautiful piece of wood. Something that gleams with its own confident beauty, without adding flash and gloss to distract from its essence. I think that idea gets at the longing that I feel. As an artistic choice, it’s very effective. I carry that story with me because of it.

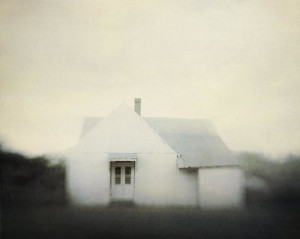

Liz Prato: Whoa, I’m so grateful for what you’re saying about the “unfinishedness” of Covered in Red Dirt, because some people DO think it’s not finished. They’re like, “Where’s the end? What happened?” But the outcomes weren’t the actual story for me. The story was the narrator’s stasis—and it’s hard to get stasis on the page in an interesting way because, generally, nothing happens and that’s inherently dull. But there is a certain kind that occurs when you’re in Hawai‘i—especially on the more rural islands, like the Big Island and Kaua‘i. It starts out feeling like relaxation, or harmony, but can easily morph into not acting, not making decisions.

MA: Yes. The narrator’s stasis–such a good point. Colors are an intense and evocative part of this story, too. Beginning with Kimo’s brown skin with white splotches, then the bed’s red-brown koa wood, the red dirt everywhere, the yellow surfboard, the blue waves…and then the ending! Those final words: “bright white.” So good. It’s a sensuous, color-saturated story for me as I read and then I get slapped by that glorious and perfect ending. Was the use of color intentional on your part? Or simply an intuitive result of the writing process?

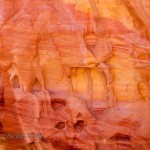

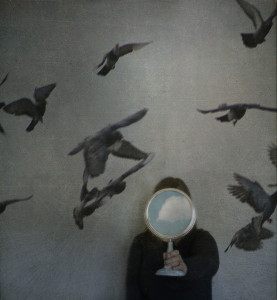

LP: A little of both. It’s impossible to write about Hawai‘i without writing about the natural landscape, and it’s impossible to write about the landscape without color. Kaua‘i is saturated with all these insane shades of green and blue and brown, and the red dirt is everywhere. I was aware that once I got red on the page then blood was on the page by association, and that opened up the story in a corporeal way. Also, race is an issue in Hawai‘i. People like to say it’s a perfect melting pot, and race doesn’t matter, and that’s ridiculous. Race matters deeply. Skin color has meaning. It’s a huge part of how people identify themselves and others. But the vitiligo (which I have in real life, by the way) is also a metaphor for how our identities get split.

MA: Another one of the standout stories for me was “A Space You Can Fall Into.” Wow. You have this wonderful talent for succinctly and devastatingly conveying a whole moment–distilling a whole life-changing moment–in just a few words. Words that are ostensibly about something else, but we know–we KNOW–what is being said, without being told. My very favorite writers do this and it slays me every time. In the passage I’m thinking of, a young girl (Shelby) is having decidedly non-romantic sex for the first time in the bed of a pickup truck with a friend of her cousin’s whom she has just met:

“…she looks up at the sky and notices it for the first time: you can see stars here. All of them. Every star that was ever made, whether it still exists or not, looks down at Shelby in the back of the brown pick-up truck, and they don’t twinkle or glow or any of those other things you expect stars to do. They just burn.”

Would you like to comment on that?

LP: As a reader, I want to be able to feel what the character is feeling not just by being told, but by how the atmosphere is rendered. There’s that scene in The Stranger where Meursault describes walking down the beach towards the Arab—who he claims he didn’t intend to kill—and the surroundings are described with such sharp syntax, words like blast and strike and gasped and bleached and blade and glare. The sounds of these words make it clear that this man is about to snap under the pressure of anger and violence. When you have an unreliable or detached narrator, like Meursault, or one who’s emotionally guarded, like Shelby, what that character won’t say outright needs to be rendered through how they see the world. Because that’s still my job as an author, to let the reader into the world, even if the character might not want to.

MA: That’s so smart–and similar to the problem from that first question about how to show the narrator’s stasis–though in Shelby’s case it’s a sort of emotional stasis. You’ve tackled these difficult narrative choices and made them work in fascinating ways. I also appreciate your deft touches of humor. Your deadpan delivery often catches me by surprise in the best way. I’m thinking, specifically, of Meg’s scenarios for Celia in “When Cody Told Me He Loves Me on a Weird Winter Day.” Humor is such a complicated thing and can be difficult to do well. Can you talk a little bit about humor? Its benefits? Its pitfalls? In writing and/or in life.

LP: Just today I sent my husband this gallows-humor text about my dad’s first of several suicide attempts, which happened exactly 8 years ago. If someone didn’t know me, the whole thing would seem pretty bleak and even unstable, but my husband texted back “Haha!” Thank god I married someone who gets that humor as a survival tactic. It lifts us out of whatever micro-tragedy we’re mired in, and gives us a chance to breathe. Even in some of the saddest episodes of my life, I could still locate the small absurdities to laugh about. It’s not a coincidence that the first two stories you mentioned—Covered in Red Dirt, and A Space You Can Fall Into—have almost zero humor and were written during a real dark period in my life. I couldn’t see the happy or hopeful ending, and couldn’t see the humor then. But for the most part, that deadpan or gallows humor will always be a part of how I approach the tough stuff.

MA: Me, too. I’d be lost without gallows humor. It’s so versatile! So flexible! Multipurpose, even. 🙂 Can you tell me something about your current writing project?

LP: I’m working on a collection of linked essays that explore my decades-long relationship with Hawai‘i through the lens of white imperialism and pop culture. I have this deep soul connection with the Islands that started with frequent visits when I was a teenager when my dad was building a housing subdivision on Maui. It recently occurred to me that the very thing responsible for bringing me to Hawai‘i is also responsible for destroying it and its culture: white mainlanders coming in and taking the land, the a‘ina, for their own. And being a tourist continues that cycle. In the essays, I’m braiding my personal narrative of coming of age in Hawai‘i as a teenager and going there as an adult to recover from the death of my entire family, with Hawaiian history and cultural affairs. I invoke Joan Didion and The Brady Bunch–wow, there are two names I never thought I’d say in the same sentence–and language and war and the ocean and ashes. In a sense, it’s a love story. My romantic beginnings with Hawai‘i were naïve and predicated on the shiny surface. Now, my abiding love encompasses not just Hawai‘i’s beauty, but also its struggles and deep wounds.

MA: That sounds fascinating. I would love to read those essays. And finally, because we are a recovery-themed journal, what does recovery mean to you?

LP: I’ve always thought of recovery as the process of renegotiating my relationship to the world after I’ve fallen down, deep down, and needed help getting up. That sounds simplistic, like a sound bite, and it totally denies what an active, exhausting process recovery can be. It’s not like recovering from running a marathon, which is mostly about resting and taking hot baths and getting massages. Recovering from trauma or addiction or illness is about rearranging your insides. You have to accept and integrate new ideas of yourself and the world into your DNA, and it can be a painful and hard. But the other option is to live a life where I’m not fully engaged, and I can’t do that. That’s what my mom and dad and brother did, and they’re no longer on this earth. That’s a powerful reminder not to succumb.

MA: Wow. That may be the best answer to that question I’ve ever gotten. Thank you, Liz, for such a wonderful discussion.