Mary Akers: Thanks for agreeing to talk with me today. I loved your short story “Oranges” that appears in our July issue. It’s such a beautiful, wistful story and I really admire how you grapple with decades of time in what is quite a short story. The next-to-last paragraph reads:

“In the morning he’ll stand up in front of his seventh-graders. ‘History is memory,’ he’ll say. ‘It’s knowing that the birds who come coursing over your backyard are traveling paths ten thousand years older than you. It’s knowing that the clouds coming over the desert today will come over this desert a thousand years from now. It’s knowing that the eyes of the ones who have gone before us will someday reappear as the eyes of our children.'”

This idea of history-as-memory is lovely. It’s also what I’d like to focus on today, if you’re game, and since your most recent book is titled MEMORY WALL, I’m going to go ahead and assume that you are. In your writing, you often travel freely through time–forward, backward, into the future, and even into the pre-human past. This gives your stories such a sweeping feel, such a massive, monolithic presence. Does this style come naturally to you, or do you have to give yourself permission to take those leaps? Do you do it confidently? Or only with sweaty palms and trembling?

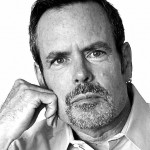

Anthony Doerr: Thank you, Mary! Thanks even more so for being a promoter and protector of literary work.

Okay, time-travel in fiction. Let’s see. I do everything with sweaty palms and trembling, unfortunately. But I take heart from the folks who have risked failure before me.

The first Alice Munro short story I ever read was “Walker Brothers Cowboy” and it includes these lines:

“He tells me how the Great Lakes came to be. All where Lake Huron is now, he says, used to be flat land, a wide flat plain. Then came the ice, creeping down from the North, pushing deep into the low places … And then the ice went back, shrank back towards the North Pole where it came from, and left its fingers of ice in the deep places it had gouged, and ice turned to lakes and there they were today. They were new, as time went … The tiny share we have of time appalls me, though my father seems to regard it with tranquility.”

As a kid I loved hunting for fossils, finding crinoids and brachiopods and (on the very best days) trilobites in the stones around our house. And I loved making timelines out of long scrolls of paper and trying to understand the size of a human life in comparison with larger, geologic scales of time. I remember one analogy in particular stuck with me, one my mother (a science teacher) taught us in middle school: What if a single calendar year, she asked us, represented the entire four-and-a-half billion year story of the Earth?

The Earth, we established, would form on January 1; single-celled life would show up in late March. Animals with skeletons wouldn’t evolve until late November. Dinosaurs wouldn’t show up until Christmas and would be gone by the 27th. Recognizable homo sapiens didn’t show up until 11:48 pm on December 31st! Columbus fumbled his way to North America 12 seconds before midnight!

That exercise freaked me out and excited me all at once. Egypt, Greece, ancient China–great civilizations, who fought wars and built temples and created whole literatures, could fit into a few seconds on the calendar year of the planet’s life? To a child, this represented a radical re-ordering of humanity’s place in the universe. Mom and Dad hadn’t always been there! Abraham Lincoln hasn’t always been there. The idea of “Ohio,” the idea of cultivating vegetables in a garden like my Mom did–those things hadn’t always been there!

Like Munro’s character in “Walker Brothers Cowboy,” I was beginning to understand that I was only going to exist on Earth for an appallingly brief time: that I was hopelessly mortal. This knowledge is what made me want to communicate some sense of the larger scales of time in my own work. For years I couldn’t figure out how to do it. But when I came across Munro, and saw how she used time (and then later Andrea Barrett, and Italo Calvino), that she didn’t believe short stories had to take place in one evening, or in one room, or in one day, I found my permission.

Incidentally, this knowledge, that life is short, is what made me decide, at a ridiculously early age, that I wanted to be a writer: I wanted to do what I loved to do before I ran out of time.

MA: That’s beautiful. I hope you get as much time as you need to say what you want.

A few years ago, I was privileged to attend a great lecture by Kevin McIlvoy in which he talked about the beauty and the value of “somatic writing.” Writing that you feel in your bones, in your soul. In the West, he says, we are moving farther and farther away from feeling. We test our children on facts without remembering that feeling the world is just as important. Neither do we teach them (or remember ourselves) to get worked up about language. He read from Anais Nin and referenced her work as being very emotional, very feeling-based, sensation-based. “I only believe in fire,” Nin wrote.

He told us to think about children, about how engaged they are in their world. “For example,” he asked, “how many of you have reached down to pick up an object off the floor of the Little Theatre…and put it in your mouth or nose?” Children are all about sensation. We can learn from them. He believes that our first gift is physical aliveness, and after that comes intellectual study/awareness.

He proposed using the word “prehension” to describe the act of being without words, feeling that there is something there…as opposed to “comprehension,” a word we all use. He said that writers are often trained and encouraged to intellectualize their work, to separate themselves, but seldom to feel as they write. Your writing style comes to mind when I think of work that I would call “somatic.” What do you think about this concept and is that something you consciously strive to be?

AD: Wow, I love Mc (well, I’m lucky enough to know him a little and call him, “Mc,” but I don’t know how the heck to spell it. Mac? Mack?). He’s very good at those lectures.

No, I don’t think I try consciously to write “somatically,” but I am very interested in how stories and novels can transport, and transport absolutely. I’m very much a believer in John Gardner’s notion that fiction writers stitch together dreams, and that we don’t want to unconsciously break those dreams and wake our readers up. So I spend lots and lots of energy trying to make my sentences as sensual and grounded and seamless as they can be. And the best way to do that–the best way to transport a reader into another place, another life–is through moment-by-moment sensory detail: through the mouth and the nose, as Mc put it. The path to the universal, I tell my students, is through the individual. You reach for the stars by playing in the gravel.

MA: Sensory details are important to me, and I admire how well you incorporate them in your stories. They are especially rich in the stories of MEMORY WALL. I’ve been formulating a theory of late, that goes something like this: the sensory details that strike us most deeply are often similes that require us to conjure up a an image or sensation first, before we apply it to the written word. A super-simile, if you will. This is getting convoluted, but let me give you a specific example from your wonderful story “The River Nemunas.” Your young protagonist Allison is in a strange new world, in her grandfather’s home in Lithuania. Here’s an excerpt in which she describes her first night there: “Grandpa Z’s bed is in the kitchen because he’s giving me the bedroom. The walls are bare plaster and the bed groans and the sheets smell like dust on a hot bulb.” That description hits me hard. Not because I’m generally familiar with the smell of dust on a hot bulb, but because I get there. I first have to conjure up what I think that might smell like, and THEN I can apply it to the sheets, and then BAM! Wow, I get it. And my theory is that we readers like to do that work. We like for a description to make sense after we have done the work, but we really like having done the work, on a subconscious level. It makes us feel smart, as if we have really gotten something important. Would you care to comment on this idea of the super simile?

AD: Hmm, I love that you’re thinking about similes, Mary. The etymology of “metaphor” is super-interesting to me: “Meta” means “across” or “over” and “pherien” means “to carry” or “to bear.” So a “metaphor” literally carries something across (I think of Saint Christopher ferrying the Christ child, who grows heavier and heavier, across the river.) A metaphor freights meaning from one place to another, unexpected but apposite place. That’s what my favorite similes do: they nudge a reader’s mind, for a split second, out of the literal world of the story and into another space (often a place of memory) for a couple of words. They vibrate the string of the sentence, if that makes sense.

In “Procreate, Generate,” to use one of my own attempts as an example, when I have Imogene (who can’t have a child) put her husband’s 2-year-old nephew on her lap, I write that “his scalp smells like a deep, cold lake in summer.” I settled on that simile because it takes a reader (and Imogene) to a place outside of the immediate scene for six words, a place that’s still sensual and (hopefully) vivid and surprising, but also a place suggestive of longing, of something she cannot reach, which is the whole point of the scene: she cannot have a child of her own to hold on her lap, and this is a painful thing for her to do.

Metaphor and simile is where complexity comes from: without them, we simply tell stories that are straight lines. We write sentences that don’t vibrate, strings that only exist on one plane, and move in a single direction.

MA: Yes, a six-word escape. That’s a great line. Very evocative.

I recently watched a wonderful movie, MOON, which its director (Duncan Jones) called “intelligent science fiction.” Have you seen this movie? Basically, it forces us to think about the bigger question of human existence, most notably what it means to be alive, how we know we ARE alive, and what sort of feedback we need from the world in order to confirm/understand our humanness, our aliveness. And one of the core elements of being a human, it turns out, is our memories. (As your epigraph in MEMORY WALL confirms.) But do we own our memories? Or do they own us? (I also recently watched the movie INCEPTION which explores the idea of implanting a memory or an idea..and how far down into the subconscious mind we have to go to do that organically. The answer in the movie is three levels down–the dream within the dream, within the dream, in order to keep the subconscious from recognizing the memory-intrusion and rejecting it.) In a way, this is exactly what is happening in your title story when Luvo and Alma merge at this intense, existential level of memory. What was the inspiration behind this story? It contains so many fascinating levels. How difficult was it to write?

AD: I’ve said before that my grandmother’s journey through dementia was my inspiration for the story, and that’s certainly true, but to suggest a story comes from a single place of inspiration probably oversimplifies things.

That story was very difficult to assemble. Seven months of work, I think. I injured my knee and went through surgery (and recovery!) while I was working on it, and I spent a lot of odd hours confined to a bed or a chair working on that piece. As usual, I tried to take on too much: class, race, Alzheimer’s, a remote geography, geologic time scales vs. human time scales.

MA: It is a lot to take on, but you make it work. And how nice to have something as small as a short story bring in all these larger issues. I enjoy the layers–they inspire me.

Memory can be such a slippery thing. Two people rarely have the same memory of any event. I worked with a fellow on a non-fiction book about his life (he was banished to Siberia as a child during WWII and his grandfather starved to death on purpose so the children would have enough food to survive). After escaping Siberia, he worked for years as a psychotherapist mining other people’s painful memories, and he came up with a theory that goes something like this: “What you choose to remember, and how you choose to interpret it, determines who you are.” That strikes me as pretty brilliant, and I think your stories in this collection bear that theory out. But it also makes me think about Esther, her urgency, and the seizures she courts as an entry into the land of memory…You know, I’ve talked myself into a circle here, and I’m not even sure I have a question, but would you care to comment on any of this?

AD: Well, that’s very compelling– who among us doesn’t whitewash our own memories about ourselves? Who doesn’t glorify our triumphs, and rewrite our worst moments? Who doesn’t want to forget, or revise, our smallest failures–the time we ate a second donut, turned back to cigarettes, yelled at the kids? The only person we absolutely have to live with, after all, is ourself.

MA: Funny you say that. All this week, I’ve been focusing on memory in anticipation of our interview, and guess what happened? An old friend of mine from high school contacted me on Facebook to remind me about this nice thing I had done for her that she has remembered all these years. (Basically, I ran laps with her when she was in trouble for arguing with our track coach. If she hadn’t run the laps, she wouldn’t have been able to attend the end-of-year banquet.) I had zero memory of this. Even after she described it to me, nothing. But for her it was crystal clear. So…I have no memory of doing a kindness, but she has this lifelong comforting memory of a kindness being done. How odd is that? Do you think we are programmed to remember the nice things done for us more than the nice things we do? Is it some biological imperative of a social society? And yet how many of us are haunted by the things we have done that are not nice. The unkind word, or the bullied kid we didn’t stick up for, or the hurt we caused another. Those are rock solid memories for most of us–and also the good stuff of fiction. Do you try to give your characters regrets as a way to bring them to life on the page?

AD: That is beautiful and strange and interesting and mysterious, Mary. Here I am thinking we try to revise our memories of difficult moments to protect ourselves, and here you are saying you’ve forgotten one of your best moments…

MA: I’m fascinated by the way Luvo becomes Alma near the end of “Memory Wall.” I’ve had dreams that feel so real my brain actually turns them into memories. A dream-memory. What’s that about? It’s like a computer taking a cookie from your Internet browsing history and turning it into an executable file. File: Dream; Save As: Memory. There’s some serious subconscious crossover going on in that case. Fascinating, isn’t it? Have you ever had this experience?

AD: Super-fascinating. Yes, I willfully and consciously wanted to play with identity in the title novella (and in “Afterworld” as well). I’m always interested in oppositions (Canada versus Kenya in “The Shell Collector,” Alaska vs. the Caribbean and ice vs. water in About Grace, etc.), and who could be more opposite than Luvo, the poor, erased South African kid, and Alma, the privileged, white, semi-racist widow? As dementia erases Alma, her memories fill up Luvo. To conceive of ways to have their identities eclipse each other engaged me from the start, and kept me writing through to the end.

MA: I think every reader has a special short-list of writers that they know they will always enjoy reading. My short fiction list would include Margaret Atwood, Rick Bass, Andrea Barrett, Ann Patchett, Barbara Kingsolver, and Anthony Doerr (not in that order). If you were to put on your intellectual/critical hat for a moment, and leave aside the fact that one of those writers is you, what would you say all the writers on my short list have in common?

AD: Wow, that’s an interesting question–thanks for including my work in that company, sheesh. Let’s see: All are North American? All write in English? Those are mostly trivial commonalities, though. How about: All pay attention to place, and believe that setting is more than window dressing, more than something a writer injects into a story like a nutrient? All believe that where a character (any human being) lives fundamentally determines a person? That we are becoming more and more divorced from place by corporations? And that sentences should do more than simply deliver action? That stories should be big, spiky, beautiful, strange, idiosyncratic, rich experiences?

MA: Lovely. I agree. And finally, because we are a recovery-themed journal, what does recovery mean to you? Or even better, what role do you think memory plays in the act–the art–of recovery?

AD: Hmmm. Recovery implies a kind of prior injury, doesn’t it? A wound or illness? Something from which to recover? So obviously memory is something that must be managed and controlled–our memories of traumas are always odd and often unreliable, aren’t they? As we recover, sometimes memories keep us from returning to dangerous places, scary moments, things we ought to face once more—here I think about people getting back on the horse, getting back behind the wheel, getting back into romantic relationships, etc…

And memory must be preserved, too, right? So that we understand what the former world was like, before the injury, before this new, recovering, overlapping world arrived? Here I think about deforested mountains, oceans stripped of life: what are we hoping they’ll recover to? And I think about war: how wars are always remembered by the victors, how the victors determine the memories people are allowed to have.

For me I think all of life is a kind of pendulum: encouragement to discouragement and back; wakefulness to sleep and back; illness to recovery and back…

MA: Brilliant. Thank you so much for participating!

AD: Thank you, Mary!