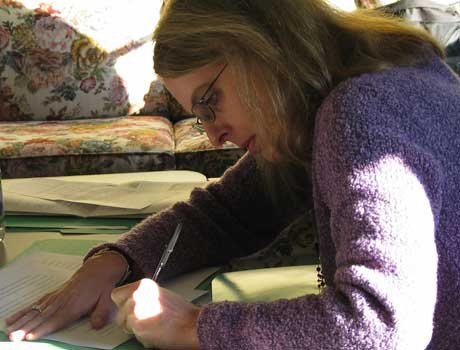

Hunter Campbell: Congratulations on being published in rkvry!

Maureen Lougen: Thanks. It’s great (and surprising) to be among such outstanding company in such a wonderful journal.

HC: We’ve briefly discussed writing in the abstract before, but not in the specific, so let me get right to it: your story God’s Forgottens is a compact tale of love and redemption. Where did you get the idea for it?

ML: Honestly, I have no idea, other than it jumped off of the Rolodex of story ideas in my brain one day and refused to be ignored. Most of my stories and novels are about

something terrible happening to a person and they try and hide from it, and someone else from that person’s life finds them wherever they are, whether they’re hiding internally or externally, and brings them back into life. So, this was just one more cog in that wheel. Or – one more entry in that Rolodex.

HC: It’s a spare telling, very minimalistic in details and dialogue. Was that a conscious choice or just the way it came out?

ML: I’m not sure that anything I write is a conscious choice. I watched the story take place through the bartender’s eyes and listened to him describe it, and he’s apparently not one to waste words. One thing I’ve learned in all my long years of writing – the reader is much smarter than I am and can fill in all those bits of detail much better than I ever could.

HC: Did you notice that nobody in the story actually has a name?

ML: Caught that, did you? Yeah, the narrator, the bartender doesn’t know anybody’s name. He’s a good guy and a better bartender and he knows his clientele. He knows they don’t need or even want anybody knowing their names.

HC: Do you know their names?

ML: Oh, yeah. I mean, it took me writing a couple more chapters, but I found out what their names are. Most of them anyway.

HC: Where did you get the title for the story?

ML: I stole it from the narrator’s dialogue. When I heard him describing the patrons as “God’s Forgottens” I knew that had to be the title.

HC: You stole it from the dialogue? Isn’t that your dialogue? You wrote it, didn’t you?

ML: Honestly? No. Well, yes. But – I don’t create dialogue as much as I listen to the characters talking and then just write down what I hear. I didn’t hunt around in my brain for a name for the narrator to apply to his patrons; I just listened to him describing the scene and that’s the name he came up with. Most of the stories I write, it’s just a matter of me watching the scene unfold and listening to the characters talk and just writing it down.

HC: He has an interesting “voice”, the bartender. Do you know someone who talks that way, or did you make that up?

ML: I think it’s half Mater from the Cars movie (we watch that a lot at our house…) and half I don’t even know what. It’s just how I heard him talking in my head. If I can hear a character’s voice clearly, my job is half over. I find it hard if not impossible to write a character whose voice I can’t hear.

HC: For some reason, the line about Godzilla coming into the bar off the lightning storm really caught me, it’s a great detail.

ML: Thanks. I live half a block from the shores of Lake Ontario, and one night last year there was a dry lightning storm and I took my son down to the end of our street to watch it over the lake. Some clouds were bluish, some were reddish, and as the lightning jumped from one cloud to another, the phrase “Heaven & Hell playing keep away” came to me, and I knew I had to use it in a story. So into the Rolodex it went until I could put it into this story.

HC: You started writing when you were still in single digits. Do you remember the first story you ever wrote?

ML: I don’t remember the story itself, but I distinctly remember the thrill I got when I wrote it down and then realized that I could go back and read it over and over again. I remember thinking that that was the best thing ever. I was hooked.

HC: Your son Joshua recently turned 10. Did becoming a Mom change your writing?

ML: I don’t think there’s a single thing that becoming a Mom didn’t change. Joshua is the single biggest influence in my life. He’s outgoing and brilliant and charming and totally oblivious to the effect he has on people. How people are just drawn to him. A friend of mine said that having Joshua is the best thing that happened to me because something as simple as going to the store isn’t just going to the store, it’s having to stop to talk to fifty people. Because – no surprise since I’m a writer – left to my own devices, I am not a people person. I’m an I’ll-sit-in-the-corner-and-write-while-you-go-somewhere-else-and-not-bother-me person. I’ve always been that way, even at family functions. But with Joshua, my life has opened up to countless new situations and meeting people by the dozens. I don’t know if that’s changed my writing per se, but it has definitely changed my life.

HC: What’s the hardest thing about writing?

ML: Having to stop writing to do something else. Anything else. If I have a minute to think, I’m thinking about writing. It’s like putting a videotape in, watching a movie play, “watching” my stories play out, tweaking them, polishing them, writing them even if I’m not at that moment writing them down. These days though, I’m more likely than not to have my attention called away every other minute by my son, “Mom! Guess what?!” and “Mom – look! Mom! Watch!” and “Mom! C’mere!” I love and adore my son. He’s the best thing that ever happened to me. It’s just when I’m in my head writing and I have to switch gears to focus on something else, it’s like stopping a tape and having to rewind to get back where I was.

HC: What was the hardest thing about writing this story?

ML: When I found out I was going to be published, it was the middle of the night, and I had no one to tell! Joshua and I were in Nashville for a convention, and it was after midnight when we got back to the room and Joshua went to sleep and I fired up my laptop to check my email. There was the email from Mary saying she wanted to publish the story – and no one I wanted to call was awake to share the news with. I had to wait until the next day. That was incredibly hard on my poor, fragile ego.

HC: Is your family supportive of your writing?

ML: Very. Especially my sister Mare. Every Christmas and birthday and vacation that involves souvenirs, she makes sure to keep me well-supplied with pens and paper. She listens to me when I rattle on about my characters like they’re real people I actually know, and she either knows or knows how to find out the answer to most of the questions I ever pose to her when I’m stuck in a spot in a story. Actually, now that I think about it, she probably would’ve been okay being rudely awakened at 2am to hear my good news.

HC: What are you working on these days?

ML: Lots of things, unfortunately. It’s hard for me to single out one thing to work on exclusively until it’s done. I usually have a dozen stories going all at once. I don’t know if that’s fear of failure or fear of success. Or adult attention deficit disorder. But – amongst the many things I’m working on, I’m trying to finish the next 2 chapters of God’s Forgottens and get them ready for public consumption. I also have some stories for sale on Amazon and I’m working on their next chapters as well.

HC: What stories do you have on Amazon?

ML: There are three so far. The Badge, which is set in 1852 Texas. A Scatter of Bones, which is set at the end of the Civil War. And The Best, which somehow managed to actually have a modern day setting, go figure.

HC: Do they all have the theme of recovery?

ML: They do. Most of my stories do. Well, The Badge not so much. A Scatter of Bones is about a young man returning home from a Confederate prisoner of war camp and trying to figure out where he fits into his family again. The Best is about a motherless little boy who’s supposed to write a paper for school about what moms do best. The Badge is about a teenage boy who has to bring in the man who shot and wounded his father. There’s recovery in a broad sense in the first two stories, but not so much in the third. You know, until I write the sequel.

HC: Are most of your stories part of a larger series?

ML: Apparently. I never plan it that way, but after a story is done, or even while I’m in the middle of it, something else in the characters’ lives will jump up into my awareness and I either start working on it right then, or it goes into the Rolodex to be worked on later. It just doesn’t stop.

HC: What does “recovery” mean to you?

ML: In simplest terms – it’s the healing after the horror.