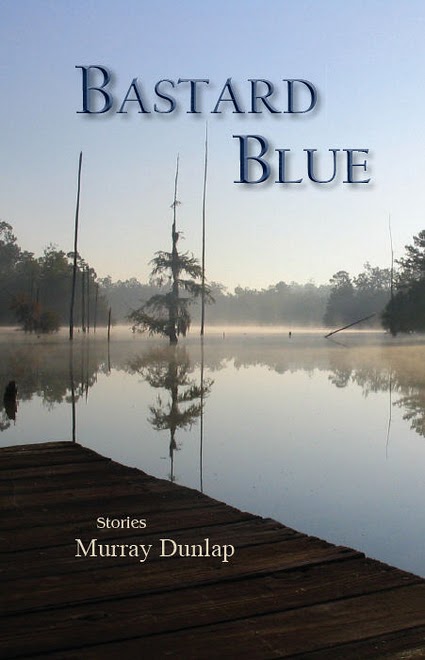

When you visit Murray Dunlap’s author website, the image that appears at the bottom of the homepage is of a horribly mangled Volkswagen Jetta. Above it is the cover of his recently-released story collection, Bastard Blue. The photo, which he took himself on family property in Carlton, Alabama, is of a peaceful, misty southern lake. This dichotomy seems to capture Dunlap’s life in so many ways—in the violent crash that changed his life so dramatically, and in the creative world that has been his oasis. This dichotomy also lives on in his stories, which foreshadow much of the suffering that he himself will face after all these stories were written.

Dunlap grew up in Mobile, Alabama. He went to the University of California–Davis, with the purpose of studying under Pam Houston, a writer he much admires. There, he married a woman from his hometown, graduated, and moved to Tennessee. In 2008, St. Paul’s Episcopal School hired him to teach English and creative writing. So, he returned to Mobile, Alabama. But just two weeks later, on his way to the recycling center (because it’s in those mundane moments that accidents often happen), and on an odd date (6-7-08), someone ran a red light and came close to killing Dunlap instantly.

But Dunlap survived. In what he calls “a time out, a time to heal,” he lapsed into a 3-month coma. What needed healing? A fractured pelvis, a broken clavicle, and the most broken part of all—his brain. When doctors, unsure if he would ever wake again, played his favorite singer Ray Lamontagne (because music, it’s been discovered, will stimulate the brain), still in a coma, he began to sing along. This was the first sign that Dunlap would revive.

When the time out was over, the hard work began. As someone with a traumatic brain injury (TBI), he suffered from amnesia. He had double vision. And this once fit young man, who had run 5 marathons and spoke of long-distance running as keeping him “going,” along with hikes with his dogs, was now wheelchair bound. Thus began the long journey back to himself. One year of therapy every day took him from the chair to a walker. And after necessary eye surgeries, his double vision improved, his balance is returning, and he recently began to attempt to jog again. “More like a crawl,” he calls it. But that crawl is a huge victory.

Along with these physical challenges came the journey out of amnesia back to himself. If you can’t remember who you are, who are you? Dunlap had to ask these questions constantly, and his marriage became another casualty as a result of this unclarity. His wife felt that he’d changed to the point where he wasn’t the person she’d married.

Therefore, Dunlap had to begin a new slate in all ways—physically and emotionally. Before the accident, he painted, photographed, hiked, ran, and wrote. Mostly, he wrote. He’d published in respected magazines before 2008, received two Pushcart Prize nominations, and an earlier version of Bastard Blue was a finalist for the Maurice Prize in Fiction. Since 2008, he has edited What Doesn’t Kill You …, an anthology comprised mostly of fictional survival stories (two are nonfiction, Dunlap’s included), and his own thematically linked story collection was intentionally released on the 3-year anniversary of his accident, June 7, 2011. Both books are published by Press 53.

So, how do you rethink who you are? Here’s a glimpse “beyond the surface” of Murray Dunlap’s inspiring journey.

Tara Masih: First, Murray, congratulations on the publication of your story collection Bastard Blue. Can you tell us a little bit about what this means to you?

Murray Dunlap: It is utterly amazing. I have been on and off again working on this book since I was in college about 20 years ago. It is an amazing thing to have, what deep down I knew was good, under my arm like a football. I finally get to cross over for a touchdown!

TM: In another interview, you discuss how you revised the collection, once titled Alabama, to suit an editor’s wishes. Then the editor dropped the book. What did you learn from this disappointing experience?

MD: I learned not to get overexcited when the paperwork has not yet been signed. Not to trust anything until it is a done deal. I learned to be a bit of a skeptic. But I have to say, due to my inexperience, I really didn’t know what I was doing with Alabama. I knew some of the stories had been published individually, but I didn’t get how it all fit together. So, now I have a collection that at last all fits together. It makes more sense as a book. I also have to say that I am glad that Alabama was not taken then. I am much more proud of Bastard Blue and, to be honest, feel it does a much better job of describing who I am and what sort of writer I am.

TM: Your stories are wonderful. I wanted to skim the book, to save time, but I had to read every word. Your use of names is intriguing—Jimbo Thames, Tripper, Elvis. Can you tell us what it is about naming that makes you pay special attention to this part of the characters you create?

MD: In my mind—and I may be making this up out of thin air—the name of the character reads into the first impression the reader is given, and therefore, puts a seed in the reader’s brain that stays with them. I enjoy naming characters and find it gratifying when a character (like Elvis) lives up to this specific quality. I also tend to be reminded of the people I know who might be a bit like the character. I then proceed to allow that name to guide me to find one in fiction, as I don’t want to be sued!

TM: Your use of dialog reminds me of Raymond Carver’s. You deftly reproduce conversation, with subtle subtext. Did you learn this from someone, or is it a natural ability?

MD: Now that is easily the most flattering question I have ever been asked. Carver! He is maybe my all-time favorite writer. I think what I have learned in dialog started with Michael Knight and ended with Pam Houston. Now those two writers—like Carver—have a knack for being honest within the character that is remarkable. I try my hardest to emulate these two in all of my dialog, every single time.

The thing about dialog is that it must be truly honest. If you think for even a second, “Hey, that guy would never say that”—the honest flow is ruined. Honesty with the character’s world is paramount. I’ll say it again. Within the world of the character, the writer has to maintain a running sense of what he or she would or would not say. It has to be honest.

TM: You’ve said that writing has helped you recall your personality. In what ways? What has come back to you?

MD: Rereading scenes in my own work has been extremely revealing. I do believe that my sense of humor has been the most easily attained part of me to get back. By reading my own dialog and seeing what the characters think is funny and why I, as a writer, think it is funny, I can figure out the context. For example, the way the men at the bar in “The Black Oyster” story have a natural jibe with one another is funny to both the narrator as well as the reader—I hope.

Also, as another example, “The Dogs Go Too” taught me about my love of the canine species. I guess I didn’t need to relearn that, but it has been good to see that I was like—

and am like—the person I want to be. A dog-loving writer with a touch of a sense of humor.

TM: Yes, there is gentle humor in your writing, and dogs are ever-present. And wolves. I loved “A Wolf in Virginia.” What about these creatures inspires you?

MD: My entire life, I have been in love with dogs. I am not sure why it is that I feel the need to understand them, but it has carried over to wolves. I think in wolves we see a truly wild animal, and we have dogs, a humanized creature close enough to wolves that we can identify with and are lucky enough to be able to recognize the beauty in. It makes me happy that you enjoyed “A Wolf in Virginia.”

TM: I couldn’t help but have this sense of constant foreshadowing when I read your book. Your stories are like the cover—the surface is placid (for the most part), but there is something lurking in the water and in the stories, which are very much layered. Alligators, car and train accidents, death masks, fire, tumors, infidelity in attic spaces, wolves—there is even a story centered around the loss of legs in “60 Seconds.” Have you realized all this yourself? Does it make you in any way feel that you had some premonition?

MD: More of an after-thought with “60 Seconds.” That story is fiction, but based on an entirely nonfiction accident where my own legs were chopped up by a boat engine. No kidding. It has also given me the feeling that I have premonitions. For example, in “Cat Stories” I talk about a girl who is forced to relearn almost everything due to a car accident. Makes me wonder what else I already know!

TM: The color blue also seems to be prevalent in your life—in the car that crashed, in your painting, in your cover, in your title, in the name of a fictional dog. Does the color have some meaning for you? Or is it just a coincidence?

MD: I simply like the parallel between the color and the emotion for which it represents. Not really sure there is any more to it? I will say that my car I was in was blue, when I was very, very close to dying in that car crash, so maybe that has given it even more weight.

TM: I also want to congratulate you on your recent attempts to run again. Since that was taken away for three years, what other ways have you found to “keep going”?

MD: So much was taken away, it has been a circus act of attempting to relearn all sorts of things. Thank you for the congratulations! Running has been such a big part of my life that somehow the addiction for endorphins managed to survive a 3-month coma and a year in a wheelchair. I’m a bit in shock that I am still plodding along!

But I also have to admit that I have no idea what drives me to do this. I suppose the waistline is part of it, but there is clearly something else at work. I am learning in this mess that I am one very determined person, and I guess maybe that’s it more than anything . . . that this has become a goal that I simply refuse to give up.

TM: I understand you did some sculpting. Tell us about the sculpture, WTF2.

MD: It’s an old college sculpture that I think had more humor in it than anything. But now that my life has become fairly dramatic, the humor has converted into disbelief concerning my present situation. Hourly, I am forced to shrug my shoulders and invent an explanation for why I can’t do something anymore. Or simply explain why it is that everything is more difficult. For example, I almost broke my neck this morning getting out of the shower. I have major balance problems, and that combined with a moment of leaning too far forward and having slippery feet . . . well, you can imagine the rest.

WTF2, plaster sculpture by Murray Dunlap

TM: Well, I’m very glad you didn’t! So you were speaking of writing when you said this before the crash, but what do your words mean to you now?: “You’ve got to have a support system as long as a river. You’ve got to know that there is no end to the struggle and that the struggle is the thing itself.”

MD: Of course! It is that trying to make enough sense as a writer to get words out there that demands a support system. And struggle is what it is all about. If we all lived in paradise, no one would need—or care—for all of this introspection, and the underlying tones of struggle in our daily conversations reveal more than most of us realize. We care because we want to know how to deal with each other, and thus, how to look at our struggles in a productive way.

So the support system I have now found outside of writing, in the process of recovery from TBI—and surely we all find this at some point in our lives—is that family and friends are not just handy for kindness, but required to survive. I can’t imagine where I would be without the love they have held out for me to hold on to.

One example: my dear mother has been my “driver” for all of this, and I cannot imaginegetting through this ordeal without her help. Because our society has revolved around the ease of transportation, that has been the most truly irritating thing to suffer through. I can drive now, but I’ll be honest, our state system simply does not work. There are so few people who work for the state as driving rehabilitation specialists, you can spend months at a time between visits. As a victim of traumatic brain injury, it is simply the state trying to keep everyone safe. And I should add that not all states have this system, and therefore, I am lucky to have the process in place at all. That said, I repeat that it doesn’t work. I owe my mother the world for helping me through this ordeal!

TM: Finally, as an artist, writer, human being, what advice would you give to people who are affected by TBI? And to their friends or relatives?

MD: Keep, keep, keep active! Never give up on yourself if it is you that has been hurt, and never give up on your friend who has been hurt. Just remember that TBI drastically affects memory and your friend may not remember what you have done to help him. Remind him! Anyone with a TBI will understand what you are doing and appreciate the help painting a clear picture of what has happened! For the one with the TBI, I cannot emphasize enough the importance of staying active. . . . Anything you used to do, figure out a way you can at least do a version of whatever it was. Like jog. As ridiculous as I look, and despite the number of times that I get called out to—“Are you OK?”—it is ENTIRELY worth it to return to this simple act of exercise. And write. I don’t think what I have written since the wreck is as good (yet), but just doing it allows my brain to return to the various connections that I was familiar with before and to return to my old self. It has given me a life back. It has been 150 percent worth it to keep trying!

Tara L. Masih graduated with a minor in sociology from C.W. Post College in Greenvale, NY. During this time, she worked as a part-time teacher’s assistant in a school for children with emotional and physical disabilities, as well as at the school’s weekend Respite Center. She also answered a crisis hotline for several years. Today, she is an award-winning editor and writer. Her most recent book is Where the Dog Star Never Glows.