“No Escape” by Peter Groesbeck

The little motel room smelled pink–fruity and warm from the soap, shampoo, all that woman stuff that Sam didn’t understand, but sometimes wanted to use when he was over at Hazel’s in the afternoon.

It was the twentieth day in a row without rain; too hot for May. Hazel’d left the bathroom door ajar as she showered and the wet steamy heat had pushed the fragrance of her out into the room where it hung like a cloud. Sam left the door to the outside open and lay down on the bed. The air was thick and sticky, but the weatherman called for severe thunderstorms to roll in overnight.

He’d come right from work and just wanted to be still for a while, lay there with his arm tight over his eyes, pressed hard so he’d see dark spots. She knew he’d come, even though he’d told her no more. He’d told her to go find some undamaged man who didn’t have a wife, a kid, who could see her all the time in the light of day. She didn’t try to argue or convince him—just got that thoughtful look on her face and said, “I’ll see you on Thursday.”

The shower was sputtering and he heard Hazel cuss the slow stream and the cooling water. He hated having to bring her here because the Tallyho-tel was not such a nice place and he worried that it made Hazel feel like a whore. She never complained, though.

It was better when she could get away from her teaching job in the afternoon and they could meet at her neat little house out on Back Road. It was out a ways where no one was around to see his truck parked in front, and she had that little crick that ran back behind. After it rained hard, that thing would rage like it thought it was a river and Sam liked to just sit on Hazel’s back porch and listen and think about how this might be how it could have always been. If he’d paid attention to Hazel in high school the way she’d paid attention to him, maybe he would have married her instead of Kelly and maybe Hazel wouldn’t have let him join up, wouldn’t have watched him with a tear in her eye and a baby on her hip as he left for Afghanistan, wouldn’t have been so scared and skittish a creature when he came home. Likely, though, it would have all been the same, just with a different woman, and a baby with springy red hair instead of hair so white it almost made his eyes hurt to look at it. And he would have ruined Hazel just like he ruined Kelly.

Right then, Kelly was probably getting ready to go to work. She worked late shift at the hospital in the next county. She was the woman who came around and woke people up just when they got to sleep to stick needles in their arms. She’d taken the classes at the career college and got the job while he was deployed. She’d lived on the base for a while after he’d left, but then said she couldn’t stand it anymore, the community of women sitting around just waiting to hear who’d been killed. She took the baby, only a few months old, and went home to her mama, enrolled in school, and started figuring out how life would be without him.

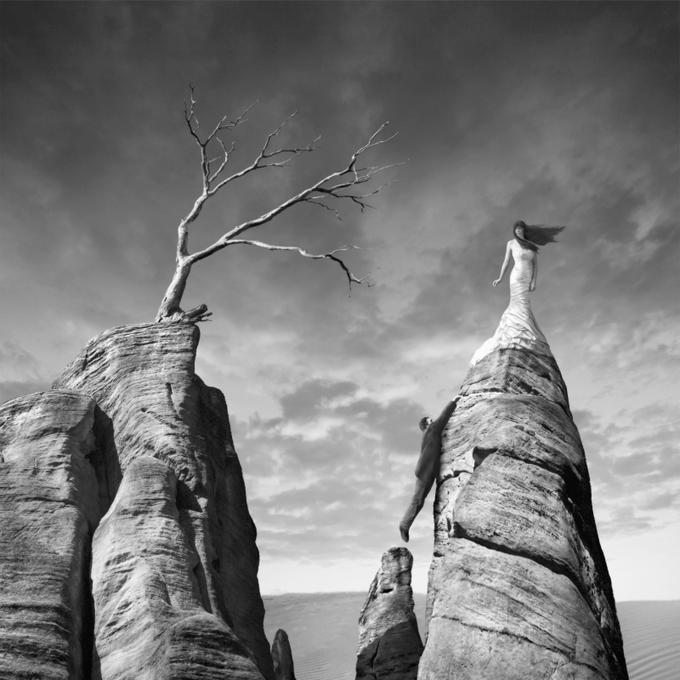

He thought it was good at first, before the explosion that ripped off pieces of him, left the skin on his back a patchwork and thick scars on his neck that everybody stared at. Before his blood had seeped into the dirt and sand so a part of him would always be over there. Now the smell of hospitals and the sight of needles made his stomach clench.

Every money problem was his because he refused to go work in the mines. He was healed enough, sure, on the outside, and his daddy could have probably gotten him on. He was retired now, but still had friends. Sam would have had to take classes and get certified, but the military would have likely paid for some of that. He just wouldn’t do it. He’d seen enough devastation. Seen houses and cars and people turned to piles of unrecognizable trash. Craters and holes, bloody earth. In his head, he knew that coal mining wasn’t the same, but inside, it still felt like it was. He would not be part of that tearing down again.

He kept his hard, low paying job on the little asphalt crew in Morgantown, patching potholes and paving parking lots and driveways. From now on, he was only going to fix things that were already there instead of trying to ruin and destroy to make something new that was almost never better.

Kelly was right, though, in thinking some things would have been a little easier if Sam had come home more like the boy who had left and more like what they all expected. If he got a job that paid better money, for instance, they maybe wouldn’t be living right in back of his folks in a singlewide trailer, having to know what every other Crystal in the holler was doing. Having always to do just what his daddy and mama wanted. Having to look over at his brother’s place across the road and know he’s not there, that while Sam was in Afghanistan walking with death every day, it was his brother, his twin, who was dying in West Virginia from a cancer that moved so quick and ugly that by the time Sam found out and put in to come home and visit on a hardship, it was too late. All he could have come home to was a funeral, so he stayed because he couldn’t stand to see Walker laid into the ground, a wasted piece of himself.

Walker left those two boys, Andy and Solomon, and Sam did try the best he could with them. At first they’d felt like strangers. Sam and Kelly’d been gone since Andy was eight and Solomon was four. Now Andy was sixteen, just one year younger than his daddy and Sam had been when he was born. Sam didn’t know a thing to do for them, and when he looked at them he saw only the ugly parts of himself reflected back. Fear and anger and confusion. That feeling of being hemmed in and wanting to run.

Lisa, the boys’ mother, wasn’t of much account, hadn’t been even before Walker died, but now left the boys home alone more often than not. Twice in the past two months Sam had been called by Tom Swentan, a friend from high school who now worked as a town cop, to come down and scrape his sister-in-law up from the Nowhere Bar and Grill where she’d passed out cold. Sam knew Tom thought he was doing the Crystals a favor by not running her in, but Sam wished he just would. He had enough of his own problems without having to worry about his dead brother’s drunk wife. And every time Sam took her home, she thought he was Walker and would try to kiss him or put her hand down the front of his jeans. The worst part, once he’d kissed her back, and thought for a minute about how it might be easier just to let himself be his brother for a while to see how that’d turn out.

Walker was always happy to stay here and work hard, party harder, be a Crystal through and through. It was Sam who was itching to figure out any way he could to go, until he did, until he went so far that all of him never could get back.

He knew that Andy and Solomon were heading for trouble. Hazel had told him how they both skipped school and then just yesterday, Chris Johnson had come and told him that Solomon had flicked a lit cigarette at his wife, Rachel’s, leg at the school house. Rachel was a new teacher, a friend of Hazel’s, and Chris said he wasn’t mad, really, but just thought Sam should know before those boys got too out of control.

Chris had come out to the job site, pulled up in his truck while Sam was shoveling down a pile of hot asphalt. They’d been good friends in school, him and Chris, but hadn’t talked much since they’d both been back. Sam knew from letters his mother had sent when he was oversees that Chris’ parents had died not too long before Walker, and that Chris had moved back to take care of his daddy’s lumber company. “It’s a sad time,” Sam’s mother had written. “A dying year.”

Sam also knew that Chris had visited Walker in the hospital right before he died, and then had been a pallbearer at Walker’s funeral. Of those things that Sam could never forgive, one was Chris for being there, and another was himself for not.

“I was just going to give you a call, but I come into town to get some things and saw you over here,” Chris said from the window of his shiny black truck. He looked just like always, just like he hadn’t aged a day. He was wearing those mirrored sunglasses and when Sam got closer, he could see tiny versions of himself reflected in the lenses.

“Glad you did,” Sam said. “I’ll take care of it.” Chris nodded and looked out the windshield. He seemed so easy there, his arm casual on the steering wheel. Sam couldn’t remember the last time he’d felt so gentle in his own skin, so cool. Usually these days he felt like fire ants were crawling all over him.

Chris made some small talk then about the job, the parking lot of the new AutoZone they were getting ready to be paved next week. He asked after Sam’s mom and daddy. “And how are things with you?” he said finally, looking over at Sam with those damn bug eye glasses, and Sam knew that behind those lenses were soft, pitying eyes. “How are you doing?”

“Some good days, some bad,” Sam said and shrugged, as if it didn’t matter. Chris nodded and stared out the windshield again.

“We should get a beer sometime,” he said. “Like the old days. Remember them?”

“I try not to so much,” Sam said and tried to laugh, but it came out wrong, not like a laugh at all, but a gagging sound or a strangle.

“Yeah, well,” Chris said and started up his truck. “I guess I better get back. You come by the house sometime, huh? Rachel’s a terrible cook, but we’d still like to see you.”

“Sure,” Sam said, though they both knew that Sam would never show up on Chris’ front porch. Hazel had told him that Rachel was expecting a baby, but Chris never mentioned it. They weren’t friends who shared good things anymore.

After he left, that whole day, Sam felt the fire building up in him. He didn’t even ask Solomon what he’d done, just grabbed him in the front yard and pulled him by the arm over to the old stump behind his daddy’s house.

“What’d I do? What’d I do?” Solomon was crying and trying to pull away, and Andy was coming up behind them, hollering at Sam to stop, but nothing could have stopped him then.

Out back was the stump from a big old maple tree that had been cut down when Sam and Walker were just kids. It was the perfect size to sit on while you leaned a boy over your knee for a whipping. Sam had been taken to that stump plenty of times, but not as many as Walker. Solomon was a big kid, but Sam was bigger, and stronger too, and full of rage and embarrassment.

“Chris Johnson had to come out to my work and tell me about you,” Sam said, spitting the words, hot and ugly. “You know how that felt? Having him out there?”

“I didn’t! I didn’t,” Solomon was gasping for air.

“You ain’t so big now, huh?” Sam had him over his knee and for the first few hits, Solomon still squirmed and tried to pull away, but then went limp and just whimpered. Sam didn’t know how hard he hit, or how many times. He didn’t know anything but how Chris Johnson looked in that big truck, that shame he felt when he saw himself in Chris’ mirrored glasses.

“That’s enough,” someone close to Sam said, but Sam didn’t stop until his daddy grabbed his wrist as he raised his arm up in the air for another smack. “I did say that is enough.”

Solomon sort of rolled off his knee then and crawled over to where Andy helped him up. Andy’s face told Sam that he’d kill him if he got half a chance, and probably Sam deserved it.

The commotion had brought both Sam’s parents out, and his Uncle Clarke and Aunt Ginny, too. Kelly was standing on their porch, holding their kid tight to her hip. She had such a look on her face, some fear but mostly disgust, and Sam wanted to bend her over his knee, too. And his daddy. He wanted to bend the whole wide world over his tired knee and whip it until he felt better.

“Well, Jesus H., Sam. You ’bout gave me a heart attack.” Hazel was standing in the doorway of the bathroom, a dingy looking towel around her and another wound turban style on her head. “How long you been here?”

“I don’t know,” he said, looking at her askance from under his arm. “A little while. I shouldn’t of come.” He could see her eyes going over him, taking in his dirty clothes and no doubt thinking of the dusty outline he was leaving on the bed. She didn’t say a thing, though.

“It’s hot. I think it’s really going to storm,” she said, standing at the open door and looking out for just a minute before going to the dresser. She got a big comb and he watched as she unwound the towel, rubbed her hair vigorously a few times, and then began pulling the comb through the wet strands. She had thick, curly hair, dark copper. Sam had some vague memory of her from high school, her hair a wild frizzy mess, but since then she’d decided not to fight her hair’s nature, or her own, anymore. “I am what I am, I guess,” she’d said. “No use trying to change it.” Most days her hair hung in bouncy coils. Sam liked to wind each finger up in one, coating his fingers in silky bits of her.

“Come here,” he said. “Please.”

“Hey,” she said, leaning over to kiss him. Her wet hair dripped onto his face, like balm to a burn. “You’re burning up. You’re always so hot. It’s like you just keep all that heat from the day bottled up in you somehow.” She kissed him, her lips like fleshy fruit against his dry, sandpaper ones. He wanted her to say to him then, “What will you do for me, Sam? What can I ask?” because it would have been anything. He would have given her anything to just soothe him like that, for a little while. He wanted to agree to anything she asked then, when he couldn’t think about it. If she’d ask him to leave Kelly, to forget about her, his family, to quit his job and lie on her back porch all day, to just be still, he’d do it. He could do it then.

Hazel moved from him, and he reached after her, catching only the edge of the old towel. When she came back, she was holding a few pieces of ice from the ice bucket. She held them to his face, slipping the ice around his hot skin, over his eyelids and lips. Around his chin, down his throat and then to the scars on his neck, down into the collar of his shirt. “This is something Mary Magdalene would have done for Jesus,” he thought, and the feeling in his chest grew and swelled up into his throat like a choking sob or an ecstatic scream.

Hazel straddled him. She said his name close to his ear, said it again and again as if trying to remind him of who he was. He moved his hands up her calves, and then smoothing over her shoulders, his skin dark from the sun and hers so pale and freckled; her all soft, round curves. She let the towel fall to the floor. She, nothing rough or hard. The magic in Hazel’s glowing skin, her copper hair, the way she remembered the old Sam and believed him to still be somewhere inside. If she just would, she could make him forget what it felt like to hit Solomon out of control, to see himself in Chris Johnson’s eyes, to feel like the best part of himself was left behind or buried. She could pull his teetering body back from the edge, keep him from turning finally into ash. If only she would.

“Ask me,” he whispered. “Please, just ask me.” She laughed a little against his neck where she’d been kissing the soft spot beneath his chin.

“I didn’t know I had to ask,” Hazel said and moved her hand to the buckle at his waist.

Sam turned his face into the comforter as Hazel undid his belt. How could she ask if she never even knew?

He heard a low rumble of thunder from outside, the storm moving closer, and the pressure in the room was building as if to spark. If only the rain would come to push down the dust and wash it all clean. Or strong winds to blow it all down. A flood. A tornado. Some excuse to start again.

Natalie Sypolt’s work has previously appeared in Willow Springs Review, Kenyon Review Online, Queen City Review, Potomac Review, Oklahoma Review, and Kestrel. She’s had book reviews appear in Mid-American Review and Shenandoah. She is also the 2009 winner of the Betty Gabehart Prize, sponsored by the Kentucky Women’s Writers Conference and was shortlisted for a Pushcart Prize in 2010.

Read an interview with Natalie here.