Randon Noble: I love the immediacy of using the second person. What made you decide to use “you” instead of “I” for your essay Fifty-four Weeks?

Annita Sawyer: I decided I wanted to experiment with point of view, just to see what I could do. It was my idea of daring. I’ve wrestled with my relationship with my younger self for as long as I can remember; if I were to identify my emotional unfinished business it is allowing myself to risk feeling compassion for the girl I was in the hospital.

The psychological testing experience had always remained vivid in my mind, and I remember my amazement, and relief, when I found a reference to this particular event – his question and my incorrect answer – in the hospital records. I’d described the scene with myself struggling to answer the psychologist’s question in the memoir, but I wanted to expand it. Addressing my younger self from the present proved more intense than I expected. I actually began to care. Once I had those feelings and began to respond in my older, wiser present voice the essay took off.

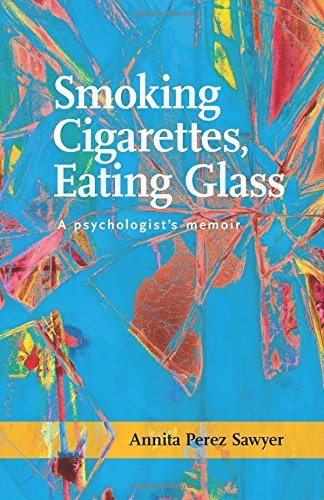

RN: You have a memoir coming out in June — Smoking Cigarettes, Eating Glass: A Psychologist’s Memoir, which was selected by Lee Gutkind for the 2013 Santa Fe Writers Project Literary Awards nonfiction grand prize. Very exciting! But it can be difficult for a memoirist to decide what stories to tell and what stories to keep private. Can you tell us a bit about your process?

AS: The book grew from the experience of reading my hospital records and finding myself thrown back into my past. What I naively thought might take a few months – “I’ll be done by the end of the summer,” I said in April, when I decided to send for the records – dominated my life for a number of years. With significant support from a skilled and experienced therapist I gradually extricated myself from the scariest depths. I emerged with insight about trauma, which was a relatively new area of research and treatment in 2003 compared with what we know today, and I felt an urgent need to pass on what I’d learned.

The process involved two books, in effect. I signed with an agent early, before I knew much about writing or memoirs. She had read only an initial collection of perhaps twenty scenes or stories centered on my hospital experience. She felt changed by what she read, and encouraged me with her enthusiasm and gave me a few ideas about what it needed to be complete. I’d say that in general she was pretty hands-off, but she believed in me, which was huge. Of course, I was delighted to have a respected agent, but I was completely out of my depth, and too inexperienced to really appreciate that. About a year and a half later, I’d completed a simple version, all in the present tense. Present tense made the hospital scenes powerful, but it didn’t include the perspective people wanted from the psychologist side of me. Although my agent received many “rave rejections,” as she called them, after more than a year of sending it out, we both knew the book had to be revised.

Meanwhile I was developing as a writer. I understood that to be viable the memoir required more depth. During the next few years I think it had at least five different titles, illustrating the fact that I hadn’t yet quite found my way.

As a writer, I tried hard to give myself at least an hour every morning to write, but I often failed. I was also working full time in my psychology practice. Most solid work came during residencies, where there was time, inspiring settings, and generous artists and writers (like you, Randon!) who gave me advice and encouragement. Kit, my agent, had often told me not to focus exclusively on the book but to write essays and stories, to try out all sorts of writing. After a zillion tries I finally had my first piece accepted, a narrative essay about getting shock treatment as a nineteen-year-old.

For chapters and essays the process remained consistent: I’d have a picture of an event or an interesting piece of information and I’d write about that. I took early drafts to my writers’ group and their feedback essentially taught me how to write – how to have my stories not sound like a clinical report! As I expanded the memoir, the middle years especially, my group gave me further ideas about what needed to be included – or discarded. I grew more discerning about what was helpful and what wasn’t. Between the writers’ group, writer friends who read it and commented, and my own literary education it gradually came together. Occasionally, I’d suddenly recall a scene that might capture an aspect of my experience that was important (for example, my first date with a man I met in the hospital). Several months after my 50th high school reunion I realized that this experience would make a straightforward last chapter. I continued to fiddle with pieces here and there – I could fiddle indefinitely – but eventually it felt complete. I was done. This doesn’t mean it couldn’t be different or better, but it touches on all of the points I think I’ve wanted to make – necessary and sufficient pieces. Some readers want more sex or family history, or information about ECT (electroconvulsive therapy), but I can see that this just means that there are more books to write!

RN: I remember learning year ago that Amy Bloom, the author of one of my favorite short stories “Love Is Not a Pie,” was also a therapist. I was both surprised and not surprised. Later I read a New York Times article, “Therapists Wired to Write,” that made me see how closely the two practices – therapy (on either side of the couch!) and writing – can relate. (How) do you take inspiration from your clinical work? And (how) is your clinical work influenced by your writing?

AS: My mentor Daniel Miller was a master clinician. He taught us the importance of being direct. Yet, if the truth you are dealing with is painful, the way you address it is critical in how it is heard. Unless you’re careful, the person you’re speaking to won’t hear it, and you won’t accomplish anything. I watched Dan use metaphor to communicate these messages. Metaphors speak the truth but leave some room; one can connect them with oneself or not, or hold the image and make sense of it later. I learned to consider the impact of every word I might say. I realize this is what writers do, too. And yes, there are unimaginably complicated stories from real life, which have helped me keep my own stories in perspective. I’m also inspired by how hard my patients work. I say to myself, if they can demand so much from themselves, I need to do the same. So I take more risks in my office and on the page.

RN: I love that r.kv.r.y pairs a piece of art with each piece of writing. Sometimes the art is representational, sometimes abstract. What did you think of the painting paired with your work?

AS: Initially, the piece paired with my work made me think of a frozen waterfall – ice and snow on piles of rock. It felt cold. After I read your question, I looked more closely. I saw faces among the rocks. Above the faces I saw branching lines and lighter patches that changed the snow into wet packs and ECT. It still felt cold, but now more dangerous, more ominous. I felt more isolation and fear than I had wanted to imagine.

RN: Is there a question I haven’t asked that you wish I had? Is there a question I asked that you wish I hadn’t?

AS: I like your questions, Randon. I love to ponder new things. I’m especially intrigued by you asking about the artwork and my associations when I looked closely. I’m impressed by its impact. Given my feelings around the essay, I can’t say how much of my reaction comes from my own projection, and how much others would see (or, more likely, feel) the same way.

RN: And finally, what does “recovery” mean to you?

AS: If you had asked me a dozen years ago, certainly fifteen years ago, I would have said recovery is when you have put your disruption and pain behind you, and you’re able to “be yourself.” But I would have meant “return to normal.” I used to believe that good enough therapy would heal anything.

Now I respect that there is no “normal” – we’re all lumpy and imperfect in various ways, which is not necessarily a problem. But with trauma especially, although we can grow and change, we don’t undo what has hurt us. Now I see “recovery” much more often as “gaining useable substances from unusable sources.”

My goal in clinical work and in writing is to enable myself and those I work with to find understanding and compassion for ourselves and one another, to respect what harm has been done, to recognize the ways this might show up in everyday life, yet to come to terms with it and move forward nonetheless. Harm can be mitigated, but it’s never completely undone; we’re never “good as new,” we’re different from what we might have been. However, with increased insight and greater emotional depth, we just might be more interesting this way!

RN: Amen! Thanks, Annita!

Pingback: Fifty-four Weeks? | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal