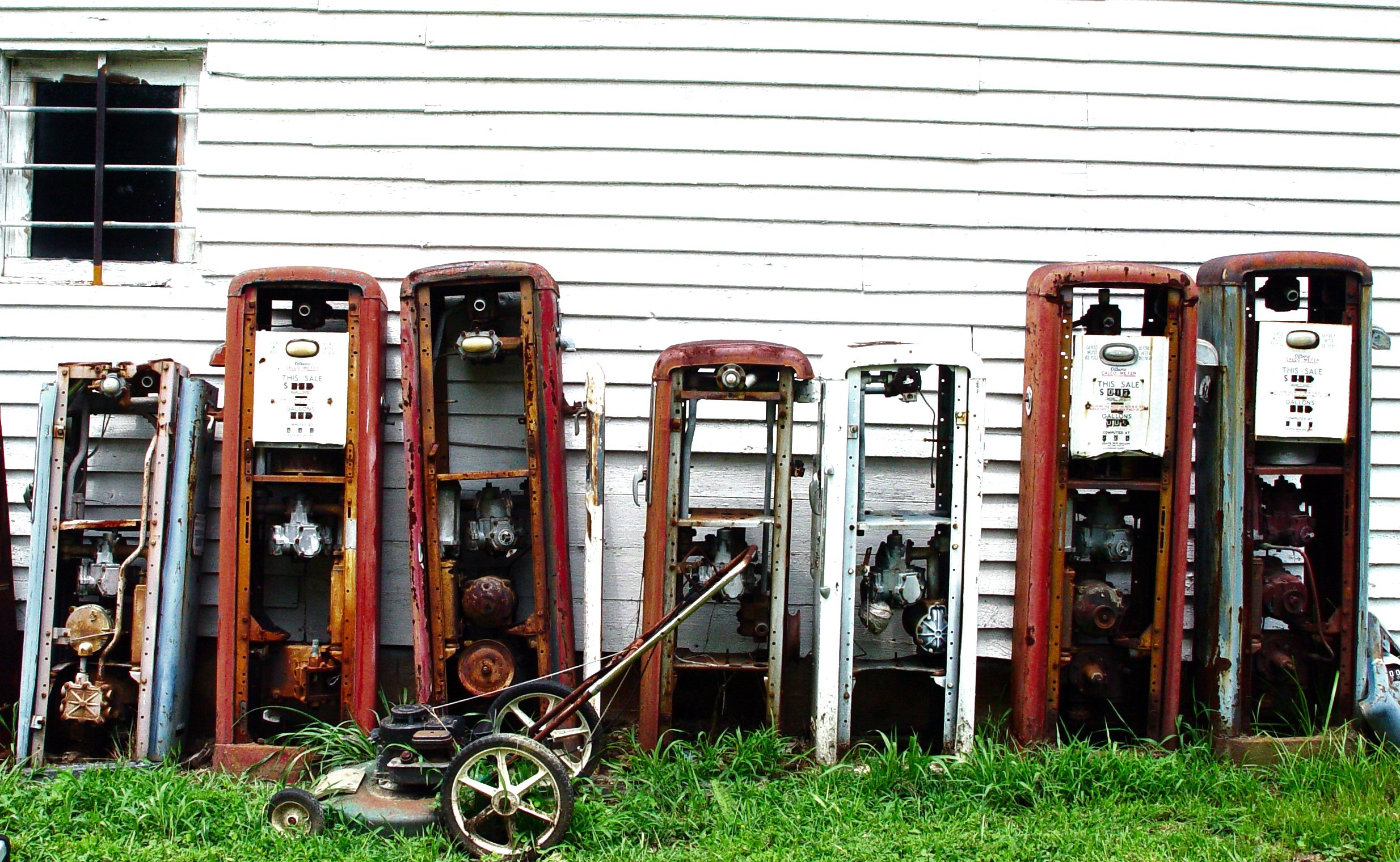

Image courtesy of Jenn Rhubright

Joan Hanna: We were so pleased to have “Bearing Down” in the July issue of r.kv.r.y. This was a very interesting retelling of an incident that happened just before your grandfather’s suicide. Although you begin your story stating that your grandfather committed suicide, this was not the focus of “Bearing Down.” Can you give us a little more background into how this story came about?

Brian Hall: First, I want to say how happy and grateful I am that “Bearing Down” found a home in r.kv.r.y. I never imagined five years ago, when I began to focus on this essay, that I would find a place as perfect for it as r.kv.r.y. I guess you can say I began the essay almost immediately after my grandfather had committed suicide in 2003. I knew I would have to write about it to understand what the hell had happened, or, more accurately, why it happened, which, I think, is a natural reaction. I know many in my family wondered why, and it seemed many friends of the family tried to stop us from asking this question. One friend of the family even came to me after the funeral and said, “You’re going to kill yourself if you keep wondering why this happened.” Though the statement’s phrasing could have been less fitting to the situation, the message was clear: asking why is the most dangerous question because, many times, the easy answer is to blame ourselves, to say, “If I only visited more,” or “If just picked up the phone and called,” or “If just did this or that,” he wouldn’t have done it.

I think many times we believe we could have been super heroes and saved the person if we only had done one or two things differently. When in reality, as in my grandfather’s case, nothing I could have done or said would have changed his mind. He wanted out, and wanted out on his own terms. Of course, that hasn’t stopped me from asking why and dealing with the subsequent blame. When I seriously began to work on the essay, I decided to focus on the “blame” aspect. I wanted to explore that last moment I saw him alive and show how I missed an opportunity to really talk to him. I realized, in hindsight, that his failure to answer the, “What’s the matter with you?” question, is my failure to see that he had not come out of his depression at all, and really, what’s bearing down on me is what happens when I focus on blaming myself: guilt.

I didn’t get serious about writing the essay until 2006. Before then I did try to write about it, but many of those early drafts were more cathartic than reflective. I believe I needed the catharsis before I really could honestly reflect on the suicide and my grandfather’s life. Though there was something really satisfying about writing down—unleashing really—a litany of obscenities to describe him and his actions, I was able to really focus on the essay while in the MFA program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. An exercise in a Creative Nonfiction class was to write a short essay while staying under a set word count. I chose either 800 or 850. I decided that I would try to honestly reflect on my grandfather’s suicide for this assignment because I wanted to keep it simple, focusing on that last moment I was with him. I also didn’t want the suicide to be a surprise at the end, which may have created a more sentimental essay than I wanted, so I decided to lead with it, letting the reader know, matter-of-factly, that my grandfather committed suicide and here is what happened the last time I saw him. It was important for me to maintain that matter-of-fact tone throughout the essay because, again, I didn’t want to be sentimental, which I think would have weakened the essay.

As you can probably tell, I am very aware with sentimentality. I’m not saying that there is never a time or a place for it, but I think a writer needs to pick his or her spots to be sentimental because sometimes a sentimental moment in writing comes off as cliché. For example, when my mother called and told me what happened, I reacted like someone in a movie. I screamed, “No! No!” into the phone, dropped to my knees, and cried. I don’t think if this essay started that way, the essay would have been very good. Even though it was true, it was not very original. I decided when I wrote it to maintain the tone and to use a moment, such as the left-foot accelerator, as my way to creatively explore a moment that could have easily been cliché.

JH: In this essay you seem, although somewhat reluctantly at first, to have a soft spot for your grandfather. Can you explain how this emotional aspect of the relationship between you and your grandfather helped to shape this story?

BH: My grandfather always had a personality that can be described as kind-hearted and also abrasive. He was always willing to help friends and family as much as he could, and he would always tell you exactly what he thought of you or your situation. Very much like the essay, when he spoke to you, it always seemed like it was your fault and that you were somehow incapable of doing the simplest of tasks. As you could probably imagine, there were many moments when he made me feel completely insecure and self-conscious because his words cut that deep.

When I began thinking about this essay, I knew it would be a personal essay (and not a nonfiction piece that explored, objectively, the suicide rate among the elderly, which was one direction I considered), and I would, essentially, be a character in it. As a character in the essay, I didn’t want to be pick one of the moments when he made me feel bad about myself because of something he said to me. If I chose a moment like that, the reader would see a kid feeling sad because an old man verbally attacked him. I don’t think the reader would have been able to connect or understand why I wrote an essay about him. Taking him to Canton for the accelerator was the best because it showed vulnerability in both of us. I appeared as cold-hearted grandson who didn’t want to help his depressed grandfather, and he was an ornery old man who really missed the way his life used to be.

In short, the emotional aspect allowed my grandfather and me to become characters in the essay, and we had our own strengths and weaknesses. I think it is important in a personal essay to show the reader that all the people involved, especially the narrator, are not perfect. I think it helps give the writing depth.

JH: What I really liked about “Bearing Down” is that it comes across as a kind of heartfelt remembrance. Can you share with our readers how you were able to add this type of detail into the story despite the fact that you were dealing with your grandfather’s gruff personality?

BH: I think the gruff personality is part of the heartfelt remembrance. I didn’t want to be around him when he was depressed because he was not abrasive, gruff. I didn’t know how to handle him when he became more introverted because, during the time after my grandmother’s death and his hip replacement surgery, he seemed weaker—emotionally, physically—than I ever remembered him. This seemed to shatter my perception of him as someone who would, and could, stand up to anybody. When he began to critique my driving and asking the “What’s the matter with you?” questions, I began to feel more comfortable with him because he became the ornery person I remembered, and I truly did (and do) miss that about him.

JH: Do you have any current projects, websites or blogs you would like to share with our readers?

BH: I don’t have a website. I’ve tried blogging at a few different places, but I’m terrible at maintaining them. I do have a few recent publications that range from fiction to creative nonfiction.

I have a short story in THIS Literary Magazine: Natural History Museum

I have essay in Shadowbox: Study Bible: The Parable of Natural Law You can find it by clicking on the center magazine and then clicking on the top right bottle. (It will make sense when you get there.)

I also have another essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education: Educating Our ‘Customers’

JH: Brian, thank you so much for sharing not only your story but also these very personal events with our readers. We are honored to have “Bearing Down” as part of our July issue. Just one final question: can you share with our readers what recovery means to you?

BH: The first word that comes to mind is “acceptance,” but I think there is more to it than that. I think it is fair to say that I’m still recovering from my grandfather’s suicide, and I have had to do more than just accept it. I had to be honest about it in so many ways, so that’s what recovery means to me: honesty.