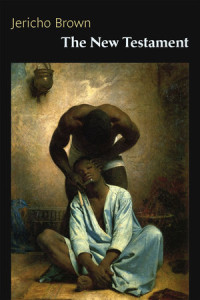

Mary Akers: Thanks for agreeing to talk with me about your wonderful collection The New Testament. I enjoyed this collection so much, Jericho. It has stayed with me for weeks, much like your other collection Please did when I first read it. In fact, I would say you write the most haunting poems–in the best sense of the word “haunting”–the specter of them hovers, they follow me around, hang about, shimmer. It’s probably a personal thing, but what do you think makes a poem “haunt” a reader?

Jericho Brown: Thanks so much, Mary!

This is very hard to narrow down. But I think being haunted means to be very aware of a presence we cannot see or touch. I guess all good poems are haunting then, because they ultimately put sounds and images in our heads that are nowhere but our heads. The poems themselves are only ink on a page. So I’ll go with music and image as an answer for now.

MA: I like that answer–and now I’m thinking it could apply to all forms of writing. The term “Poetry of the Body” comes to mind when I read your work. I’ve heard several poets employ the term lately, so I googled it and came up with a page that declares, “Poetry should be read aloud, tasted on the tongue, felt in the blood and heart.” I agree, but I wonder how a poet who writes work as somatic as yours feels about that definition. What do you think it means to be a poet of the body?

JB: The “poet of the body” is one who reaches for revelations that are made in and through the body before they are fully understood in the mind. I want to believe that poems ask us to make use of our instinct and intuition, that they create feelings in us similar to hunger or to an itch. When we get these feelings, we know we need to eat or that something could be crawling on our skin.

MA: Yes. Beautiful. So…bearing in mind that artists and their work can fit into many different categories, would you place your own work in the category of Poetry of the Body?

JB: I don’t try to do any categorizing of myself. It would take all the fun out of writing if I bothered to place myself in such ways. And because I’m so skeptical of my own habits, it would lead me to writing against something that may well be the thing that makes my poems particular.

MA: Reading your wonderful collection also had me thinking about form. You manage to create work that feels simultaneously structured and free, precise and ecstatic. I really admire that. It’s like watching a potter throw a pot–every precise, practiced movement combines to create this fluid dance of hands on clay that looks effortless. Eventually that fluid clay becomes a hardened, finished vessel. Magic. So…structure and freedom: how do you strike these contradictory notes so beautifully in your work?

MA: Reading your wonderful collection also had me thinking about form. You manage to create work that feels simultaneously structured and free, precise and ecstatic. I really admire that. It’s like watching a potter throw a pot–every precise, practiced movement combines to create this fluid dance of hands on clay that looks effortless. Eventually that fluid clay becomes a hardened, finished vessel. Magic. So…structure and freedom: how do you strike these contradictory notes so beautifully in your work?

JB: Thanks, Mary. Some of this happens simply because I’m bold enough to believe that it’s there. Some of it happens because I revise until my eyes hurt. I like things that look effortless, which is why I like listening to people like Brandy Norwood and Cindy Herron and India Arie and Lalah Hathaway. But I also love to hear a good deal of effort from time to time, which is why I’m attracted to Karen Clark Sheard. I try to be open to anything happening when I write a first draft, and I start pushing for something greater than that so-called freedom while revising.

MA: One of my favorite poems in The New Testament is the heartbreaking ghazal “Hustle.” (If I might stay with the question of form a moment more.) When I was in art school, if a professor told me to create whatever I wanted, I would often freeze up–too many possibilities! But if I was told “Make something this size, using this medium, etc,” I found that the constraints actually freed my mind and I was able to be even more creative. It was as if the fences helped me wander. Do you find creating art that sticks to form to be a freeing experience? Or narrowing?

JB: Form is often the best thing that’s ever happened to me because it asks me to search myself for words and rhymes and rhythms I may not naturally fall into. This pushes me to say things that I don’t expect myself to say. And of course, that’s the joy of writing a poem.

MA: You have three, related and untitled poems in the center of the book. Five, actually, but the three are directly related and the other two inform them. I have to say, this sequence totally sneaked up on me and by the last one I felt like I’d been gut punched. So powerful. I’m curious, did you always envision these poems working together in this way, or did that only come about in the process of organizing the book?

JB: Oh, I actually think of “Motherhood” as a poem in five parts with each part on a different page. I didn’t want it numbered because of the narrativity I thought the prose parts would already gesture toward. And, I thought it important that the parts in lines work as a kind of foundation that gives rise to what goes on in the prose poem parts. I’m glad to hear the poem is of use to you.

MA: Ah, okay. That makes perfect sense–form is the answer!

A recent reviewer had this to say about your work: that “…the same words and phrases, and ultimately, the same speech, can be read as either erotic or political or religious…” That speaks so succinctly to one of the things I love most about poetry in general and your poems in particular. They get AT so much with precise but also duplicitous words. Have you always loved words? If not always, then when do you remember feeling that love for words develop. Can you point to a specific memory?

JB: My grandmother used to say things like, “You ain’t got a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out of.” I imagine growing up around people that talked that way all the time taught me that language had fabric. I always wanted to hear older people talk because the way they talked was in and of itself an experience; an experience even greater than the information of the stories they told. When I think of what I want to do as a poet, I think of that.

MA: As a fellow southerner, I hear and respond to that rich fabric of language in your work. And as you know, I edit a recovery-themed journal (in which some of your wonderful earlier work appeared). I’m fascinated by both the idea and the mechanism of recovery. It strikes me that a great deal of the poems in your book have some aspect of recovery in them. So what, would you say, does “recovery” mean to you?

JB: It means: everyday I understand that the wound can lead to anything other than pain is a day I’ve survived even my own worst fears about the wound.

MA: Yes it does. Thank you for this discussion and for your wonderful work, Jericho. It enriches my life.

Jericho brown is the recipient of the Whiting Writers’ Award and fellowships from the Radcliffe University for Advanced Study at Harvard University and the National Endowment for the Arts. His poems have appeared in The Nation, The New Republic, The New Yorker, and The Best American Poetry and Nikki Giovanni’s 100 Best African American Poems. Brown holds a PhD from the University of Houston, an MFA from the University of New Orleans, and a BA from Dillard University. His first book, Please, won the American Book Award, and his second book, The New Testament, was published by Copper Canyon Press. He is an assistant professor in the creative writing program at Emory University in Atlanta.