Juditha Dowd: Your poem in this issue of r.kv.r.y, “Into the Fire,” starts with the line, “Around a Philadelphia piano bar sweaty with beads/off glass…” Years ago you moved to the Southwest from the Philadelphia/Jersey Shore area, where you still have close ties and visit often. What prompted the relocation, and what has kept you there?

Kyle Laws: I was born in Philadelphia and grew up on the Delaware Bay side of the Jersey shore. I suppose you always want what you don’t have. In high school, a friend and I plotted to go west. We wanted to experience the desert. She went to Tucson and I ended up in Pueblo, Colorado, a town on the Arkansas River, the old border with Mexico up until 1848. I came there with another friend at the time. The first stay was short, six months. Then we moved back to Wildwood, NJ, and stayed in the area for four years. I lived down the road from Town Bank, an old whaling community. I had first met the friend, a Colorado native, in Wildwood. He became my husband. After four years, he wanted to move back to his hometown of Pueblo. I followed him, somewhat reluctantly. Before leaving, I did a big research project on the historical whaling community for a South Jersey history class I was taking at the time. It was a form of good-bye to the landscape I loved. I still use the research in my writings. In many ways, being away from that landscape deepened my appreciation for it while I was becoming rooted in the Southwest. I have written about both in poems, the dichotomy and the sameness. That area of Southern New Jersey on the Delaware Bay remained largely untouched for centuries, and what people experienced when they came west in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a wide open primitive land, is what I grew up with. It was like spanning time and space. Pueblo has what was—at the end of the nineteenth century—the largest steel mill west of the Mississippi. People came from all over the world to work there. Guggenheim’s first foundry was in Pueblo. My father was a machinist at the same factory in Philadelphia for forty years, retiring from the plant in his sixties. The similarities are interesting. The ethnic mix in Pueblo is broad because of the international labor force. Many of the ethnic neighborhoods still exist. It’s an unusual place to live and relatively inexpensive. The art scene is lively. And I was able to make a living independently, working out of a Victorian house that is also my residence in one of the historic neighborhoods for thirty years now. Because of the independence, I could concentrate on writing and go back to New Jersey and Philadelphia for research and retreats. My sister lives in South Philadelphia in a brownstone she inherited from our mother. She’s very willing to share it.

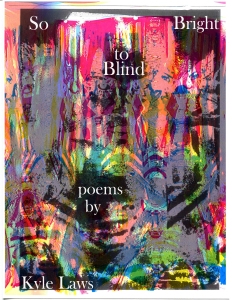

JD: In your book So Bright to Blind you tackle the subject of Los Alamos, giving voice to scientists, like Oppenheimer, and others involved in the project or someway affected. What drew you to this subject?

KL: The time of the development of the atomic bomb was the same time as the early years of the marriage of my mother and father. So much was happening in the world at that time that directly impacted them, which ended up impacting me even though I wasn’t born until the 1950s. I wanted to understand that part of history in order to understand my family. The dilemmas and decisions that the scientists faced were huge. One of the interesting books I read in my research was Oppenheimer’s The Open Mind, a book of essays on the shelf next to Marilyn Monroe’s bed at the time of her death. The cultural foresight he showed in those essays along with the apologia for the bomb ranks only after Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis written while he was in jail. Both are gripping emotionally and philosophically. And the development of the atomic bomb happened not far from where I live, in a landscape very similar, an isolated high desert that had been captured on film for decades in Westerns.

JD: I admire the way you braid historical events, geographies and lives that intrigue you. Where does inspiration typically begin—in the personal or the external?

KL: It begins in both. But often it is the external that prompts a response, something I read or see or hear. And because my natural inclination is to place it in history and landscape and within my own frame of reference related to my family, the personal comes in. I will often physically place myself in a historical setting. In late 2015, I took a studio a block from the river walk in what had been a commercial building beginning in 1891with furnished rooms on the second floor. There was a tremendous need for housing at that time for steel and railroad workers because both industries had grown so quickly. The remodeled building purchased by the Pueblo Arts Alliance for artist studios kept the basic layout of rooms. I’m in Suite A at the top of the stairs, an L shaped room. I did research on the residents and commercial tenants. Out of that came a series Woman in Suite A about a writer who came west and took a room in the building in 1922. She contributes to magazines that popped up after World War I about her life in the bustling steel town. And she befriends a steelworker from Luxembourg and a saddle and harness maker in the shop below. Both are based on historical people. I didn’t start out taking the studio to do that, but my curiosity led me there and the narratives started popping into my head. That series is coming out this year in collaboration with a photographer who integrated the poems into her photographs of Pueblo and the surrounding area.

JD: Many poems set a fragment of your own history against a desert landscape. I’m thinking now of “Roving,” “Over the Precipice” and “Running of Blanco Sol” from So Bright to Blind. Place seems very important to you, both as concept and daily reality. Do you find the desert geography particularly evocative?

JD: Many poems set a fragment of your own history against a desert landscape. I’m thinking now of “Roving,” “Over the Precipice” and “Running of Blanco Sol” from So Bright to Blind. Place seems very important to you, both as concept and daily reality. Do you find the desert geography particularly evocative?

KL: The desert is a diverse place geographically. In Pueblo, we’re in the high desert at 4,500 feet. And Pueblo is in a bowl useful for agriculture. We’re surrounded by mountains on three sides and to the east is land that was part of the Dust Bowl. For a number of years I used to walk that landscape in spring and fall, the only time it’s hospitable for hiking. From the highway and even walking, it seems entirely flat and then you come to a precipice of a canyon carved by a river. The Purgatory River is one I’ve descended a canyon to walk along. Its historical name is El Rio de Las Animas Perdidas en Purgatório, River of Souls Lost in Purgatory, named by the Spanish, first whites through here. The name gives you an idea of the desolation. Yet there are people who settled along the canyon bottom happy for the water. Electrical wires were strung on cut trees. And you can find petroglyphs carved in the canyon face from earlier peoples. The orioles that you find nesting there in late spring are visually stunning in their orange and yellow against the pale rock and tracks along the river. I never came across another hiker. That is the landscape that was used in “Roving.” “Over the Precipice” was in Canyon de Chelly in Arizona when I camped along the bottom with a Navajo guide and two photographers. “Running of Blanco Sol” was on La Veta Pass. Because we’re in a bowl, most of the ways out are over passes so they show up repeatedly in poems. All three of those poems, along with other poems in the book were part of a series I did in response to Zane Grey’s Desert Gold. He is one of the historical writers who beautifully captured the western landscape.

JD: Some poems take opera as a subject, others have a theatrical feel, like mini dramas. Does the poem initially come to you visually, as a scene? Or aurally, as music? Or … ?

KL: Many poems come to me visually as it’s a reaction to what I see. And then something strikes a chord emotionally based on experiences and the beginning of a narrative starts to take place. And as the narrative develops, it moves forward into an idea that I’ve been thinking about. And the idea could be rooted in history in this place or another, and it springs into something more universal that you can understand whether you are in that place or not, but you have the feel for where it began, an image you can take with you. Some poems do come aurally as sounds influence me, the simple call of a bird out the window, but also because there are a number of musicians in the building my studio is in. There’s a violinist across the hall. And musicians and singers practice for performances one studio down. I will hear the same song over and over, and the repetition brings thoughts of the background of the song. I hear a lot based in rhythm and blues and soul. I’ve worked with experimental musicians to give joint performances with poetry, gone to a number of concerts at their house and written while the musicians are performing. The poems that took opera as the subject were largely written while the music was being played. And if poems have a theatrical feel, that is most likely based on the storytelling I grew up with, my mother a wonderful teller of tales. Most of our experiences were bracketed into what could be considered short plays that highlighted some element of human nature. Even into her eighties, she could keep a corner of a restaurant entertained.

JD: Your interests are far-reaching, and you spend considerable time on research. Where might you take us next?

KL: I’ve written a novella in poems about Fishing Creek, the original name of the town I grew up in on the Delaware Bay. Unknown to me until ten years ago, each lot sold until 1958 contained a covenant restricting it to the white race. It’s told from the point of view of the husband and wife who were the developers, trying to come to terms with what would have been their motivations. I spent quite a bit of time for that project in the county office where the deeds are kept. The employees were quite nice to me, even though at times I would get really upset at how long the injustice had gone on, even after it was outlawed by the Supreme Court in 1948. I would ask over and over how could they have let it happen. I kept on waiting for the sheriff to show up and escort me out of the building. No one ever did.

Juditha Dowd’s poetry has appeared in Poet Lore, The Florida Review, Ekphrasis, Spillway, Kestrel and elsewhere. Her most recent book is the full-length collection Mango in Winter. She is a member of Cool Women, an ensemble that performs poetry in the New York-Philadelphia area and on the West Coast.

Pingback: “Into the Fire” by Kyle Laws | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal