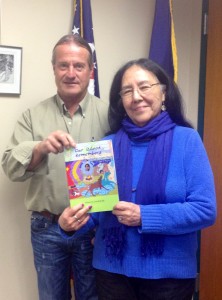

Lowell Jaeger’s fine poems Ants and Excavation appear in our October 2012 issue.

Hannah Bissell: You’re always working on something. What are you working on now?

Lowell Jaeger: I’d like to see Many Voices Press do a book of brief memoirs from past and present AmeriCorps volunteers. Short vignettes of the best and worst experiences. I’ve worked with AmeriCorps volunteers in Montana Conservation Corps for the past several summers, and I’ve totally fallen in love with these young people, their community service spirit, their giving natures, their willingness to brave weeks of exposure and hard labor in the wilderness. I wonder why they are so willing to give, so willing to sacrifice, so energetic, so engaged, so hard-working. What can I do to help the AmeriCorps cause? I could do this book of AmeriCorps memoirs, a book aimed at prospective AmeriCorps enlistees, a book to give these prospective volunteers a realistic glimpse into the challenges – victories and disappointments – of volunteer service. You’re right; I’m always working on something. I don’t quite know where to begin on this one, but it’s percolating in my head. That’s how these things grow.

Hannah: Sounds like a worthy project, but it’s not poetry. Will you be publishing more poets?

Lowell: Our big anthology, New Poets of the American West, took three years to put together. A real labor of love. A real adventure, too. Seems amazing to me that a small non-profit micro-press like MVP could have ever pulled it off – 250 poets from 11 Western states, including a Pulitzer Prize winner like Philip Levine, a National Poet Laureate like Kay Ryan, prominent Native American poets like Simon Ortiz and Joy Harjo and Leslie Silko, and poems in Spanish and 6 Native American languages – wow, I hold the book in my hands like an Olympic gold medal. I’m proud of that.

And I’m proud of the three books we’ve done by Native American poets Victor Charlo, Lois

Red Elk, and Minerva Allen. All three are risky enterprises; these deserving Native poets, now in their seventies, have gone so long without the attention their talents merit. Charlo’s book includes poems in Salish, Red Elk’s book includes poems in Lakota/Dakota, and Allen’s book includes poems in Nakoda (Assiniboine). These books are cultural artifacts, historical artifacts. These are voices singing at the margins of American culture. That’s what Many Voices Press is all about – a celebration of many voices.

So, yes, I want to publish more poets, especially more Native poets. But publishing is one thing and marketing a whole other thing. Hard these days to sell books in general, even harder to sell poetry. We’ve managed to persist through a lot of tough times. With the kindness of strangers.

Hannah: You’ve written four collections of your own poems. Do you have a new collection in the works?

Lowell: I’ve got a new collection, How Quickly What’s Passing Goes Past, now in search

of a worthy publisher. It’s a collection of poems out of my childhood in the 50s and 60s during the Cold War. I read someone somewhere who said, “Anyone who has been alive on earth for at least seven years has enough material to write about for the rest of his life.” I feel like that’s true. As a kid in the 50s and 60s I must have been walking around like grade school documentarian, listening to the conversations, filming the dramas, jotting notes in my sub-conscience. Now the memories are pouring forth faster than I can possibly shape them all into poems, sometimes four and five poems a week.

Hannah: What is it about the Cold War era that calls to your imagination?

Lowell: I was a kid with my eyes open. I saw neighborhood fathers digging bomb shelters. We hid under our desks at school when Civil Defense sirens commanded we should duck and cover. TV was new in our lives, and the /images were horrific – Hiroshima, Nagasaki. Then came the H-bomb, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Kennedy/King/Kennedy assassinations, and napalm.

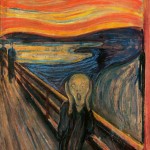

I recently saw again (on the r.k.v.r.y. Blog) the Nick Ut Vietnam War photo of the kids and soldiers fleeing for their lives down an empty road with the war blazing behind them. There’s that naked little girl – especially now, as a grandfather, I’m moved and pained by that image. But those are the sorts of /images I grew up with. I don’t know why I was so affected by that sort of thing; my brothers who shared that time in the world with me seem to have been living on a different planet. For them, the past is past. For me, the bombs just got bigger and bigger, scarier and scarier. I felt like that young boy in Ut’s photo, the boy wearing the look of horror. Doesn’t his mouth resemble that poor freaked-out little guy in Edvard Munch’s “The Scream”? That’s how I felt. That’s what many of my generation felt. That’s what this book is all about.

Hannah: Calm down. Okay?

Lowell: Sorry. Sorry to sound so bleak. The new book, believe it or not, is also filled with a

lot of humor. As scary as those times were, they were also ridiculous. The whole idea of hiding under your school desk to save yourself from a nuclear blast is ridiculous, isn’t it. Or radiation; we were always in dread of atomic radiation. Families owned their own Geiger Counters. Here, I’ll give you a humorous poem from the new collection. A poem called “The Test” which displays our ridiculous fear of atomic radiation:

The Test

Dad confided in Mom he’d heard it

from a guy at work who’d heard it

from another guy whose younger brother

worked a maintenance job at the plant

where they built the bomb.

Reports of super-secret testing, us

against the Commies, killing the atmosphere

with radioactive dust. The air

we breathed could burn us up

from inside and turn us into lepers

with bloody sores and wrinkled skin

hanging like rags. What if that’s just talk,

Mom said. Maybe, said Dad, but what about

all those babies born wrong

with no feet or no fingers or no arms?

Mom couldn’t push that thought back.

She’d incubated four boys and wanted grandkids

someday. I don’t see how that works,

she said. Why is atomic fallout

making babies born wrong? . . . Dad shrugged.

Nobody knows, he said. And would have left it,

except Mom called us boys

into the room and looked us up and down

for worries we hadn’t even dreamt of yet.

We should get ‘em tested, she said.

Well, Dad said, I think they’re safe

if they got balls in the right place.

Which is how four pre-teen boys lined up

and dropped their drawers for Dad’s inspection.

What the hell, we asked. What’s going on?

Dad bent his face close to where we’d hoped

to keep undercover. And squinched his brow.

I don’t see nothin’, Dad said. Mom looked

from a safe distance. She asked, You boys

feel all right? Then threw up her arms before our reply.

How will we know, she said. Lord, how we gonna know?

Hannah Bissell is Assistant Editor of Many Voices Press. She is currently a second year student in the Pacific University MFA Program.

Hannah Bissell is Assistant Editor of Many Voices Press. She is currently a second year student in the Pacific University MFA Program.

Pingback: Excavation | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal

Pingback: Ants | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal

Pingback: “Ants” by Lowell Jaeger | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal

Pingback: “Excavation” by Lowell Jaeger | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal