“Growing Into Truths,” Image by Dawn Surratt

1. The floorboards creaked, though none of us were home. A stranger—to us; she knew the shore house well—had broken in through the side door, stolen to the basement, and thrown a rope around a pipe just below the living room floor.

The house was built in 1929 with a cinderblock foundation, which is not often today’s method of choice. Most new houses are constructed entirely on wooden pilings, as was the newer sun porch out front, circa 1963. But the basement, like the tiny, single-level, cedar-shake cottage, was built based on codes of its era, back before the days of massive coastal development, back before the days when we had any real fear that the ocean could take the Jersey Shore away.

In 1973, Neil’s father decided to cut a hole through the living room floor and put a set of stairs into the basement, the two-car garage. In the decade earlier, he had already added a concrete slab floor to what was originally just sand and a cinderblock retaining wall that held back the dune outside. He had replumbed the pipes with little Neil’s help, bought a washer and dryer, and knocked down that back wall, shoving it farther into the dune, closer to the beach by 15 feet. In that extra space, he built himself a workroom to tinker with his fixtures and wires. He built a storage closet for linens and sunscreen and a storage room for bikes and boards, plus a small, enclosed, full bathroom with a stand-up shower that had sand in the floor paint for traction and when the garage door was open you could have the illusion you were showering outdoors.

When the stranger entered the basement—the garage—with its grey concrete floor and grey cinderblock walls, and the unfinished ceiling joists above, I’m sure she could hear the muffled ocean, could imagine its spray, could conjure all those summer days for one rental week at a time, or maybe two, when she sat out on the deck and read a book and picked crabs and drank white wine with her feet up, under the umbrella, with the dune grass rustling in the breeze. Yes, even the basement was filled with the lure of the sticky salt air of the shore, without even one window.

The police arrived at the house a day after her husband reported her missing. She had been diagnosed with uterine cancer, he had said. And she had been unable to bear children. He had strayed in their marriage, and she was suffering from depression. They were estranged from one another, far away in some other town. But he knew her well enough to tell the authorities that, even in winter, if she were to flee anywhere, she would flee to this house, which she had loved many times and had always loved her back.

2. In Arlington, Virginia, we braced for the storm.

Weeks prior, I had made plans to go to the shore house that weekend with my dad and stepmother from Philadelphia. It was to be a Friday-to-Sunday trip. On Wednesday, October 24, we looked at the forecast: simple rain. On Thursday, October 25, we debated our options. We wondered whether we would still enjoy ourselves if we couldn’t take our morning walks to the bay, that sepia stew of jellyfish and biting flies in the still air; our afternoon walks on the beach toward the mansions of Mantoloking in one directions or the ghosted face of the Ferris wheel at Seaside Heights in the other; if we couldn’t spend our nights spending our money out on the pier spinning some sort of wheel or shooting something up to win a stuffed animal and then stuffing gigantic triangles of Maruca’s pizza into our gut.

If I had been planning to go to the shore house just with Neil, we would have gone anyway that weekend, with what we knew then. We would have stayed in and listened to the ocean and to music and read books and watched the storm. Yes, we would have sat near the windows of the sun porch—all seven of them on three sides—and we would have watched the weather come in. We would not have turned on the TV because we’re not TV people. We would not have listened to the radio because we’re not radio people. If we had Internet service, we would have definitely logged on, but the connection might have been spotty. Maybe the police would have made announcements on a loud speaker, or maybe not. Without any year-round neighbors in shouting distance to warn us, we may have marooned ourselves in that house as the weather picked up. And when the lights began to flicker and the wind tore the first shingle off the side of the house and the ocean started eating away at what we thought was the ground, the earth, that solid yet moveable stuff that the deck and walkways were built on, it would have been much too late.

Instead, my dad and stepmom—wise people—suggested that it wasn’t worth all the hassle for a rainy-weather trip—five hours’ drive for me; them having to pack up again after having just been there on their own the week before, using up some of the empty days on the rental calendar. And so we didn’t go to the shore.

Neil and I did not watch TV because we don’t have cable, and we did not listen to the little, old-fashioned hand-held battery radio after our middle-of-the-night check-ins. The radar imagery we saw online of what happened was colorful, but so abstract. We did not see information or photos in the newspapers on that first day after the storm, or even the second, about the full extent of damage; they mostly published generalities and focused on our local Washington DC area and New York City. And so two days would pass before it would occur to me to seek information about how the tiny, eight-block town of Normandy Beach, New Jersey, fared in the storm.

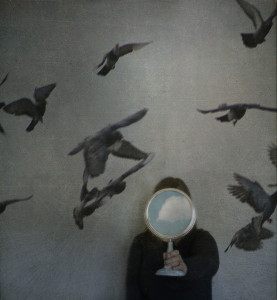

3. I closed my eyes, and the surgeon slipped a scalpel into my face. In my mind’s eye, I could see the shape he was cutting: a half moon to the left, a half moon to the right. Then he cauterized the bleeding—fumes of burning-flesh taking hold in my nose—and took the segments of skin away.

They were working on the tip of my nose. I wouldn’t know at the time that future surgeries would take segments from my left eyebrow, twice, then from the nose again. My chest, my arm. Once from the leg. These were my souvenirs from my summers in the sun, the ones when my face puffed up like a blowfish from my second-degree burns, peach-colored and fuzzy too with skin peel, and the ones when I could put a hand to my chest or shins and pop like Rice Krispies the tiny, white water blisters that formed there. Bruce Springsteen never sang about what happens to all the beach bunnies at the Jersey Shore twenty or thirty years later: their leathery skin, white splotches, cataracts, skin cancer. This surgery aims to take the blemish away, but the scars and the memories are forever.

In 1973 and 1975, the years when Springsteen released “The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle” and “Born to Run,” I was at least ten years too young for its words of teen angst. The 3” x 3” square, white-rimmed family photos from Avalon or Stone Harbor—a week or two each summer each year of my youth—show me in pigtails, with an orange-tinged visor over my face, and it’s the smell of Bain de Soleil, SPF 4, that I remember: island fruit punch and burnt sugar, a thick, meaty, orange paste. My mother and I sat together in our low beach chairs at the water’s edge near our hotel in our bikinis. Each time the water rose, I collected clams the size of orzo before they burrowed back into the sand.

By the early 1980s, I was wildly staring at cute boys from across the courtyard of our rented summer apartment or at the neighborhood hangouts of my best friends’ parents’ low-slung rental houses a few shores away, living out silent romances in my head. There, I was the girl bopping down the beach with the radio, blonde and bronzed in satin stripes, watching men watching me, poised on the boardwalk rails with the rattles and rings and greasy, fried, sweet scents behind them.

The love that was wild, the love that was real, strapping my legs around anything—none of that would happen during the years I wished it. It happened at the shore house with Neil, unsnapping my jeans under the floorboards in the basement, the aurora rising somewhere outside behind us. By then—after my doctor had warned me that basal cell carcinoma, like that on my nose, liked to keep the same company with melanoma, a deadly form of skin cancer—I had mostly abandoned the sun, affirmed by Neil’s influence as an avid non-sunbather and the kind of man whom a tan did not impress. I did not even venture to the beach, except for walks. Instead, I luxuriated in being able to stay on his family’s oceanfront shore-house deck, jutting out deep into the dune grass and hovering over the crest of the dune with a panoramic view of the Atlantic under an umbrella—with a shroud of terry cloth over my entire length, with a book and a constantly refreshed icy drink and snacks from our stash in the kitchen. I could tuck inside to the sun porch for relief anytime I wanted, with windows wide open, piping in the metronome music of surf.

The shore house was my tether. It kept me from harm.

4. Neil always said we should sell the house. Though other siblings enjoyed the place with their kids, he and I didn’t use it much, as it was too far away. Any time we went, it always seemed to ensnare him in a D-I-Y home improvement project, eating up our few precious hours. And it didn’t hold childhood memories Neil wanted to relive: the youngest of the clan, being dragged there by his mother every summer, far from his hometown friends.

But it is a family house, owned jointly by the four distant siblings after the death of their grandparents, who had bought the house in the 1940s, and then their parents, who inherited it first. Global climate change, Neil would whisper in their ear whenever he could, at a rare family event, over an occasional email correspondence. But the idea never took. Even with the framed black-and-white photos in the sun porch that showed the storm of 1962, which tore off the original sun porch addition, projecting their wisdom down upon us as we lazed in that outermost room against the shore, inertia reigned, as it is wont to do.

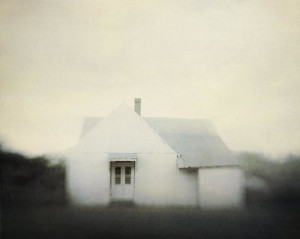

It was a dark house with small windows, wood-paneled walls, and castoff antique mahogany furniture from fancy aunts. It was not a modern beach house, not a place of new-fangled things. It did not try to put on airs; to say, I’m better than you because I’m taller, wider, fancier, or closer to the sea. It was none of those things. It was old money, and old money does not brag. Old money buys one of the first houses in Normandy Beach, not to keep up with the neighbors, because there aren’t any, but because the air is good for lungs and the sea is easy on the mind, and because it is a slightly eccentric thing to do during a war. Old money was Neil’s maternal grandfather, a banker in Trenton, and when he bought the house, the beach now crowded with Spanish-tile- and faux Tahitian-thatched-roofed mansions was empty, flat as a surfboard against all horizons. From the kitchen window, Grandmother could see him coming down the road in his car from miles away.

Another thing old money does is not try to be young again, not sell out to the highest bidder. It understands that new, brown cedar shakes will go grey with time, salt will corrode anything that shines, and that, with dignity, old money will die on its own terms.

So the siblings—the descendants: unflashy, unassuming, middle-class—did not really consider (not now, not just yet, the time is not right) or agree on selling the oceanfront double lot for one-and-a-half million dollars or two, the lot made of sand dune so deep and vast they we never really knew—until all the sand was gone, like if we were to shave our furry cat and suddenly see its real, skinny form underneath—that the wood pilings holding up the front half of the house had stood in sand 12 feet deep; that the sand at that depth had once stretched more than 70 feet across the property. The house was scantily insured. When it was all over, the family would receive the amount that the tiny, old cottage alone without its oceanfront land was probably worth, for wind and rain damage (the policy did not cover flooding), calculated based on the depreciated value of the property lost. Checks disbursed stood in for commiseration, and correspondence between the four siblings mostly ceased thereafter.

Each year since the early 1990s, each sibling has had to pay a few thousand dollars in property taxes to the state of New Jersey. The tax rate on second homes in New Jersey is high, as is the benefit for those who make use of the place—and the risk. We paid for a constant stream of new shingles, shutters, and appliances; cleaning, construction, cable, and spotty Internet, and the opportunity to go whenever we wished. It was an investment, we reasoned when the payments came due; an always-open option, a future, and a family peacekeeping measure as well.

The giant, towering house next door, two stories higher than ours, which we dubbed “The Monstrosity,” looked down upon us, out the second or third story windows, and called our place “That Thing,” for its relative shabbiness. In mid-October, a week before the storm, the last time anyone inhabited our house, when my dad and stepmom used that fateful empty week for their autumn getaway, the owner of The Monstrosity casually mentioned to my dad that he’d like to buy our shore house land. He said he’d like to raze the building, pave the grounds, and turn it into a parking lot to give his guests from New York City more room for their cars.

5. On Wednesday, October 24, unbeknownst to any of us in Virginia, or Philadelphia, or possibly even in the various places where Neil’s siblings live, near and far from the Jersey Shore, Weatherboy—a news personality on Facebook—predicted that Hurricane Sandy would strike the northeastern United States with “brutal force,” “perhaps being one of the most catastrophic fall storms in the region on record.”

On Thursday, October 25, the day my dad, stepmother, and I definitively decided we would rather not spend the weekend at the shore in the rain, which was the weather forecast we had heard—whether on the radio, on TV, or the Internet, I don’t remember—Weatherboy wrote that Hurricane Sandy would bring widely scattered tornadoes, widespread destructive winds, and extremely high storm surges, on top of high astronomical tides.

“Residents of …New Jersey…should rush their hurricane preparation plans to completion as soon as possible—your life and property is at risk from a potentially historic storm,” Weatherboy reported on Friday, October 26, when I would have been making the five-hour drive, either alone to meet my dad and stepmom, or with Neil, had we been the travelers. I had not yet subscribed to Weatherboy, however, and none of us—which is unbelievable in retrospect but 100 percent accurate—had heard the dire predictions for the storm. “In the primary impact area,” Weatherboy warned, “people should be prepared to have no electrical power (and perhaps water, gas, and heat) for many, many days…Historic disaster unfolding,” he said. “Its trajectory onto the Garden State is a ‘worst case scenario.’”

And further: “Beaches will have life-threatening conditions for a prolonged period of time—do not visit nor stay near beaches!”

On Saturday, October 27, what would have been the second day of the trip that very nearly happened, Weatherboy announced that “Hurricane Sandy continues its forward march, gaining size and intensity as it does so… with a storm force wind-field of historic proportions.” It is the “second largest tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Atlantic” at this time and is “on track to become the largest ever.”

Neil’s sister and husband and family, local to the Jersey Shore area, finally corresponded with us about the dire predictions, and on Sunday, October 28, descended upon the shore house to board up the oceanfront windows. On the same day, Weatherboy reported on Governor Christie warning New Jersey residents statewide to expect power outages lasting up to 10 days, with roads blocked due to downed trees and wires, and basic services “unable to function for a prolonged period of time due to power outages: gas stations, banks, and food stores.”

At the end of that day, the shore house stood dark and alone, abandoned, its future depending solely on Neil’s sister’s last-ditch storm preparations, a contractor in the 1960s for its sun porch re-construction, and some unknown builder in the 1920s who saw fit to locate a seasonal family cottage at the lip of the ocean—“frighteningly close to the water,” as a friend once told me.

“Brace for impact!” Weatherboy warned on Monday, October 29 and predicted that the storm would make landfall around dinnertime. Then the web site fell silent for the night, as if a hush had settled over the land.

6. If the stranger had picked Monday, October 29, 2012, to drive to her beloved shore house rental and hang herself in the basement, it would not have been a smooth transition from one life to the next.

She would have heard the surf alright, but it would have been rougher than expected. She would have heard the howl of the wind, felt the vibrations in the earth from the pound of waves, even through the concrete floor.

If she had gone out on the deck first, before her final gesture, for one last look at the landscape she once found so serene, she may have been scared for the first time at the shore house, scared to see the ocean coming ever closer to her sanctuary. Scared at the way her hair swirled around as if her finger were stuck in a socket, scared that the flagpole at The Monstrosity next door would fall. Scared to see the snow fence that once held back our big dune getting undercut by the water, starting to lean into the beach, then getting dragged away into the darkness.

If she stayed outside long enough, holding on to the rail of the deck to keep her steady, she may have begun to feel the deck move beneath her, like the rumble my dad and stepmother felt when they were at the shore house during the Mineral, Va., earthquake the previous year, an uncomfortable undulation, as if the deck were supported by rolling logs. The pressure and vortex of the wind may have begun to hurt her ears. The blowing sand would have stung her face.

At some point, she would have had to run inside because it would have been much too frightening to allow the storm to have its way with her, the uncertainty and chaos of it all, and if she had run early enough back into the house, she would not have quite have seen how the ground, the earth, that solid yet moveable stuff that the deck and walkways were built on, was melting into the sea like sugar crystals dissolving in hot water—right under the sun porch door. Looking out into the abyss, the new ground far below would have been like looking down from a high dive onto the bottom of a pool. The sea scoured the shore as flat as the highway onto the island, now busted and breached by the waves.

Perhaps she would have already been indoors when the wind lifted up the first of the roof shingles, tore off the first of the side cedar shakes, broke the first of the unboarded-up side windows, uprooted the first of the dune plants, scoured away the first of the side stairs, split the first crack into the concrete furnace-chimney, sprayed the first of gallons of rain water and sand into the living room, or heaved the first of six inches of the sun porch apart from the rest of the house.

Only one thing would have mattered, if she had been in the house that night: Was she in the basement, the garage, when the ocean—freed from the protective barrier of dune—laid out its thousands of pounds per square inch of weight and collapsed the cinderblock wall to allow the salt water through the foundation. Because if she were already in the process of arranging her final fate or already martyred, the ocean would have pummeled her like a deranged husband or waterboarded her to death.

But the stranger was not in the basement that night, had entered her own heavenly home years before. She did not get an earthy or on-the-way-to-heaven-ly view of the ocean’s lashing tongue pushing the washing machine and dryer out into the street, along with the bikes and boards and old lamps and fixtures and all of Neil’s late father’s old tools. She did not have to endure the indignity of wooden doors and sheets and towels and bottles of sunscreen gushing past her in a fast fury, with seaweed wrapping around her neck and legs. She’d never have to report that the Cadillac a neighbor had stored in our garage, to protect it while he wintered in Florida, was stripped by that ocean thief and abandoned in the middle of Ocean Terrace like a beached whale.

And she would never have to know that the bathroom with a cinderblock shower with sand in the paint to prevent slippage and a countertop that Neil and I made love on during the wild summer nights when I finally could be that bouncy, bronzed beach beauty I never was would end up in pieces scattered across the street in the neighbor’s yard.

The suicide would remain a private affair. If she had been there that night, the body may still have been attached to the pipe, waterlogged, for all the world to see—those few who stuck it out on rooftops or in fire halls, the rescue squads searching for survivors. The storm surge and record-high tide drove straight through that lower level of house, tearing a hole through it like a fist, leaving behind a floor-to-ceiling view from street to sea, an uninhabitable body of broken bones. A thread—golden, faded, or black—pulled forever from the fabric of our lives.

Years later, it sits there still; a wound still raw, a salvation waiting to be salvaged.

Sue Eisenfeld is the author of Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal and a contributor to The New York Times’ Disunion: A History of the Civil War. Her essays and articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Gettysburg Review, Potomac Review, and many other publications, and her essays have been listed among the “Notable Essays of the Year” in The Best American Essays in 2009, 2010, 2013, and 2016. She is a five-time Fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and a member of the faculty at the Johns Hopkins M.A. in Writing/Science Writing programs. www.sueeisenfeld.com