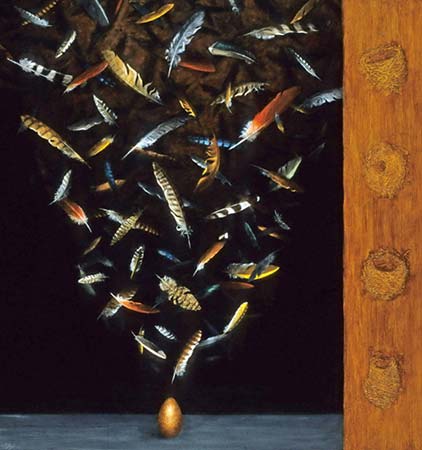

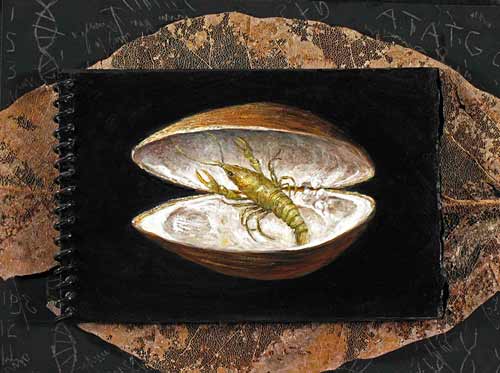

“Facts of Life” by Suzanne Stryk

“…During a summer storm of three or four days of chilling rain, flocks leave the nesting grounds and may fly hundreds of miles until they encounter favorable weather. After the storm, they return in small groups to the nests. In their absence, the young survive without food, becoming torpid: cold, motionless, and barely breathing. Lower metabolism prevents starvation, thus allowing the young to be raised through alternating periods of plenty and shortage.” ~National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds Western Region

“When your mother dies,” Matthew said, “Your molecular structure breaks down and is rearranged. When it’s over, you literally become a different person.”

Matthew is my love. I don’t know what else to call him. He endured the deaths of my father and mother, a year apart, and in between, Zoe’s murder. It was as though a hole opened up in the universe and sucked them all away.

Rather, I should say, Matthew endured my family. And me. My father refused to acknowledge him, and made snide comments about Jews. My mother adored him, but of course, my mother loved everyone. In grief, I became insane.

“Now you will truly be an orphan,” my therapist said, “a real orphan because your parents are dead and dying. And you will cast off your family.”

Cast off my family?

“Your family is the embodiment of evil.” Pam tilted her head, examining me as if for self-inflicted burns, cigarettes crushed out on my belly. “I see you standing on the porch of a burning cabin. You can go back in and rescue everyone. Or you can save yourself. You’ll be lucky to escape with your car keys.” Pam wore a silly purple beret and jaunty scarf. She didn’t care what other people thought about her. “Have you read the Old Testament? You must cleave unto your lover.” That shut me up. Pam quoting the Old Testament. Sucked as I was into the tarpit of my family, it seemed logical I should jettison Matthew. If I increased my losses to the highest possible level, I wouldn’t have to feel anything at all. It was like pressing on a bruise on my wrist to ease the throbbing in my skull.

After decades without drinking or smoking, I wanted to drink and smoke. I’ve never done heroin, but that sounded fine too.

If not heroin, throw myself off a cliff.

“Want anything to take the edge off?” Pam asked. Sweet words. But I knew from long experience that I wouldn’t simply ease the edge.

“I’d take one, then the whole damn bottle, and then crave more,” I said. “But if you give me an IV I can lead around on a leash, with just the right dose trickling in? I’ll take that.”

Instead, I walked for miles in the Olympic National Park. I walked so far and so fast my collie and golden retriever couldn’t keep up. I walked until I reached an altered state. Adrenalin or endorphins or exhaustion kicked in, or the sun streaked through the trees to illuminate a single fire-singed stump, turning it blue and black, and at the same moment, a Pileated woodpecker made its “high clear series of piping calls” overhead.

My toenails bruised and turned blood dark, like those of a marathon runner.

Dad died first. Matthew and I left Manhattan and returned to the Pacific Northwest. It was a long dark spring, or so I remember: rain without ceasing. We were shipwrecked in our cabin, death and darkness folded around us. Sometimes, I wanted to be even more alone, in a tiny space, like a baby’s crib. I wanted to move into our guest cottage, called Eagle Cottage because bald eagles perch overhead. I wanted a cell-like bed separate from all others, to be attached to that bed by a slender chain, floating away from time.

Yet I could not sleep unless Matthew wrapped himself around me, holding me tightly, forming a womb, and even that was not enough. I never lost awareness of my mother, a few miles away. After sixty years of marriage, she slept alone in her own cell-like basement room in the hospice. I wanted to fashion a pouch, like those in which newborns are swaddled, clutched to the chests of their fathers or mothers. I would carry my shrunken little mother twenty-four hours a day, singing to her in her own dying days.

Every dawn, I awakened to a heavy fist of dread striking my heart. I dreaded visiting Mother, and then felt guilty for my dread. I dreaded her actual death. I was sad about my sisters, and how estranged we had become. I fantasized the lovely sisters again united, singing perfect four-part harmony. This happened, briefly, at my father’s memorial down on the shore. After the guests left, the siblings sat on the grey stone sea wall Dad had built by hand. It was dusk. We sang every song we remembered, someone starting one up and the rest picking it up, on and on, until the moon rose red over the horizon.

And then the next morning, the calls and texts and emails began, the awful things this person said, or that.

Sometimes I woke with renewed energy to take action, to quit feeling sorry for myself. I wanted to accept death as a natural, even healthy part of life. I wanted to accept death as beautiful, a way of prayer, a simple cessation of heartbeat and breath. I did not have to die because Dad died, because Mom was dying. Yet the child, alone, without parents, does die. If she can’t find sustenance or shelter, she dies.

When Matthew and I were in Manhattan, I taught a class on addiction, weight and body image. It was nice to be around teenagers. The women, girls, really, were beautiful and brilliant. It was difficult to understand how they could hate their bodies, want to hurt themselves, cut into their flesh, as most did, but Manhattan is filled with ambition, and even the very young are driven to accomplish by thirty what others, in other parts of the country, the Northwest for example, might be content to achieve in a lifetime.

Two days before Matthew and I were to return to Portland, one of the young woman called. She begged me to attend a “ladies tea,” as she called it, in my honor. I had already begun to push the students from my mind, my way of protecting myself from loss. “I can’t,” I said. “I have too much to do. I like clean departures.”

Zoe insisted. Sweet Zoe was spectacularly beautiful, a gifted singer and piano player, on scholarship to Manhattan School of Music. She had a glow about her, the same glow my mother had, but she also had a craziness I couldn’t quite put my finger on, perhaps only my own madness when I was nineteen.

“We want to celebrate your Kirieness,” Zoe said.

And so the dozen women from the class gathered in Zoe’s studio apartment. Everyone dressed up, and perched along two facing couches, and on chairs, chatting about this and that. I was staring out the window at a brick wall, thinking about Matthew and my dead father and my dying mother, and then, as if from nowhere, as if from far away, I heard Zoe say “I trade sex for groceries.”

She needed groceries to feed her child, her scholarship didn’t cover food. Or child care.

I didn’t know Zoe had a child.

“Oh yeah,” she said. “I lost custody. See, when I was eleven, this guy talked me into going to his apartment, and then he raped me. When he was done, he threw, like a hundred dollars on me. On my body.”

“How awful.” My heart went out to her, this beautiful smart young girl, her life shredded. When I was the age Zoe was now, in art school and working as a model, the same thing happened, and the guy threw a few dollars on a chair. This is all I’m worth? I remember thinking that.

Zoe said the man became her pimp. And she was on a yacht one day, and the client left for a moment. She felt something beneath the bed, poked with her high heel, and she saw the body of a woman shoved underneath. Still in her heels, Zoe ran for her life across the dock.

I wondered if this was how I sounded, too, at her age, when I tried to tell my sisters or my friends what had happened. Zoe cried a little, but the tears fell straight down onto her beautiful dress, as if beyond her bidding.

Then Zoe laughed. “I escaped,” she said. “I’m alive. I’m starting over.” She would regain custody of her little girl. She would finish school, support her family. Relieved, we all laughed too, a glitter of sound across the darkening room. Zoe poured chamomile tea into fragile cups, passed around trays of lemon cupcakes.

“Violence changes the brain chemistry,” I told the young women. “Experiencing it, I mean.” I cannot help talking like a professor. It’s better than feeling. “Talking about these experiences with each other lessens the pain,” I said.

“I’m going to be a therapist,” Zoe said. “Like you. I’ll do music therapy with young girls who’ve been damaged. And help them live.”

A week after our gathering, when I was already back west, the story was all over the news. Zoe met a man who was once a client. She met him in a hotel room where they’d often met before. She thought he was in love with her. He was a law student, and maybe he would help her with college, with her daughter. It seemed he wanted to tie her to the bed, or tried to. Zoe ran, actually made it to the door, and then he shot her in the back.

“I’m hysterical,” I told Matthew. “I’m so sorry. I should know better.”

Matthew disagreed about what I was, what I should be sorry for. “Hysteria is deep healing,” he said. “The more deeply you cry, turn yourself inside out, the deeper the healing.” He said grief is like being hit by napalm, immolated and melted. Or boiled to a grinning skeleton of bone.

“I would rather light myself on fire than continue to cry like this.” I put my hand over my belly as if protecting an embryo. “If my molecular structure changes now, what will I be when it’s over?”

“It’s never over,” Matthew said. His parents had died decades before. I’d always felt sorry for him, but now I envied him.

“Was it like this for you?” I asked. “Did you feel like this?” Every day, I asked him that.

As our mother embarked on what the hospice nurse called “active dying,” we four sisters gathered a final time. We sat around our mother’s narrow cot and sang every song we knew, the songs she taught us. We folded our coats into pillows, and slept on the floor, breathing ragged as she did. When she stopped breathing, she looked like herself again. Her folded-up body straightened out. She was beautiful, like concentrated sweetness.

I howled like a baby, a pierced animal.

“I’m not sure I’m coming back this time,” I told Matthew.

“I know,” Matthew said. He reached over and touched my knee. “I’m not sure either. Let’s just go ahead for now.”

When I was attacked, I left my body. I saw the event, but I was outside it, looking down from near the ceiling. I never returned to that body. That girl was dead. I developed the head, the brain, and even some of the credentials to help others. I did help others. I didn’t save Zoe, but I’m sure I helped a few people.

That day, when Matthew touched my knee so lightly, I re-entered my body. Just as the assault took place at a specific time and place, on a specific day, to a specific body no longer mine, so I returned to my new body, this rejiggered constellation of molecules, almost with a thud. It was as if a screen or shroud lifted all at once. Below the cabin, the high tide lapped on the grey stones of the shoreline, and in the Douglas fir and madrona clung small clusters of golden crowned kinglets, bushtits, creepers, and nuthatches with their tumbling chatter, their tinkling descending warble. I shook my head and looked around at the waxing gibbous moon, the turquoise water. The moss was freshly green in the cold spring rain. I wanted to pet it. I wanted to lie down in it and roll around. I wanted to pray to it. I wanted to learn its name.

Kirie Pedersen has work forthcoming or published in Quiddity, Wisconsin Review, Eclipse, RiverSedge, Utne Reader, Folly Magazine, Eclipse, Women NetWork, Alcoholism the National Journal, Northwest People, Caper Literary Journal, Laurel Review, Teachers and Writers, Regeneration (Rodale Press), Glossolalia, Avatar Review, Chaffee Review, Black Boot, Eleven Eleven, Folly Magazine, and elsewhere. She holds an M.A in fiction writing and literature and blogs at www.kiriepedersen.com