The Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

The minute we turn off Meathouse Fork Road, the Appalachian mountain roads go all one-lane and twisty. My night vision isn’t good, there are deer around every turn and switch-back, and locals who could drive this stretch of road blind are impatient behind me. But my friend Brad is kind. He just laughs a little when I say that this might be the scariest part of our planned ghost-hunting adventure.

By the time we arrive in Weston, WV it is good and truly dark and I can’t see far enough beyond the gleam of headlights to get my bearings, so Brad takes over as navigator.

“Which way should I turn?” I ask.

“Left,” he answers.

“And now?” I ask.

“And now?”

He guides us to a CVS, though how I don’t know. Something about the way the streets lay out makes sense to him in a way it doesn’t to me. I buy flashlights, because it’s only just now dawned on me that the old state hospital in which we’re about to spend the night probably doesn’t have electricity. We’ll be glad for them later, because—except for a break room and two bathrooms—it doesn’t.

The guy at the counter is in his mid-fifties, with the lilting accent of central West Virginia, and so I tell him where we’re going because I hope he’ll have stories.

“You’re doing the ghost hunting tour at the old hospital?” he asks, after I’ve just said we are. He doesn’t say asylum, like the website does, or mental hospital, the colloquialism with which I grew up in hills not far from here. The hospital—first, the old one we’re going to visit, and then the new one which took its place a little more than a decade ago only a few miles away—has always been the lifeblood of this little Appalachian town, and so the locals afford it as much dignity as they can.

“I remember when I was about fifteen or sixteen,” he tells us, “walking down the sidewalk beside the fence at the hospital when I should have been at school. There was this lady there, one of the patients, and she kept pulling up her skirt and her stockings.” He pantomimes a woman lifting her skirt up above her hips and showing off the tops of her stockings seductively. “I said, ‘Lady, I’m only about fifteen years old. You ought not to be doing that’.” He laughs. “But I remembered it all these years. Yes sir, I never did forget it.”

This may be the only true story we’ll hear tonight about the patients at the Weston State Hospital, now a “historic” and “paranormal” tourist destination operating under its original name: The Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum.

Arriving

Copperhead, a man with long red-grey hair in faded jeans, boots, and lots of faux-pagan jewelry, calls everybody out into the main hallway when it’s time for the tour to begin. “We got a few rules we need to go over first,” he says, his thumbs hooked into his belt loops. The rules are simple. Don’t take food out of the break room, because they’re tired of having to clean up after people. Don’t smoke except in the two designated areas; outside through the doors behind us or on the second-floor balcony just off the old doctor’s quarters. No drugs or alcohol, even if you brought enough to share. He explains that we’ll be split into two groups of twelve. One group will start on the first two floors, the second on floors three and four. After an hour or so with our guide, we’ll be free to split up and explore those floors of the hospital on our own. After four hours, at 1am, we’ll switch floors. The tour lasts from 9pm to 5am. “And be respectful,” he says. “These ghosts were people. Are still people. Don’t provoke them.” Then he smiles a carvnival-barker smile and says, “If you want to know what I mean by provoke ‘em, I mean don’t act like Zak.” Everyone else in the crowd laughs. Brad and I look at each other. Neither of us has any idea who Zak is.

The Guide

Sarah, a short middle-aged woman in sweatpants and an OK Kitty scarf, tells us she drove for more than an hour to be our tour guide, spending pretty much all of the sixty dollars she’ll be paid for the night in gas to get here. When I ask her why she’d do that, she says she loves the building. And it is an amazing building, nearly a quarter mile long, with beautiful hand carved woodwork and unexpected beaux-arts touches. Sarah says it’s the largest hand-cut stone building in North America. Even this claim, when I try to verify it, proves illusive. It all comes down to how one defines largest.

“I read that the workers who broke ground on the hospital were ‘Negro convict labor’ (I make air quotes because I’m incapable of using the word Negro without them), slaves who’d been set free when West Virginia broke with Virginia, but who were then immediately arrested for being vagrants and put to work by the new state,” I tell her. “Is that true?”

“Oh, God, I never heard that,” she says, shaking her head. “It could be. We don’t like to talk about the more unpleasant parts of the hospital’s history.”

Floors 1 and 2

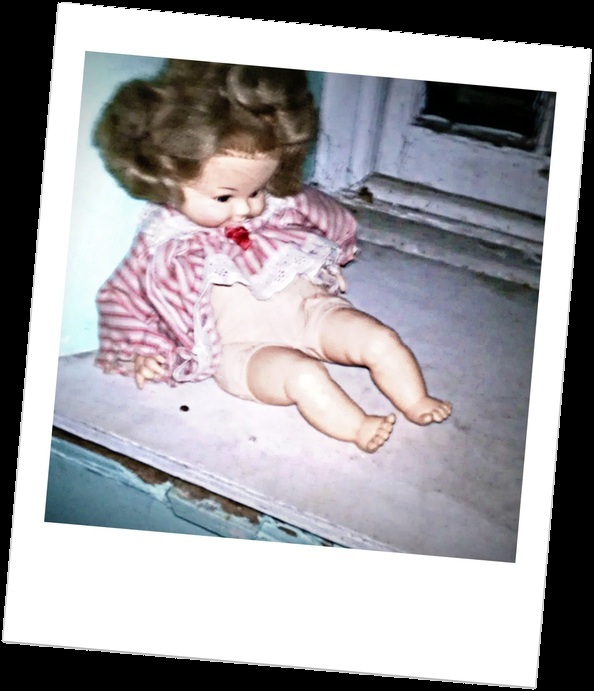

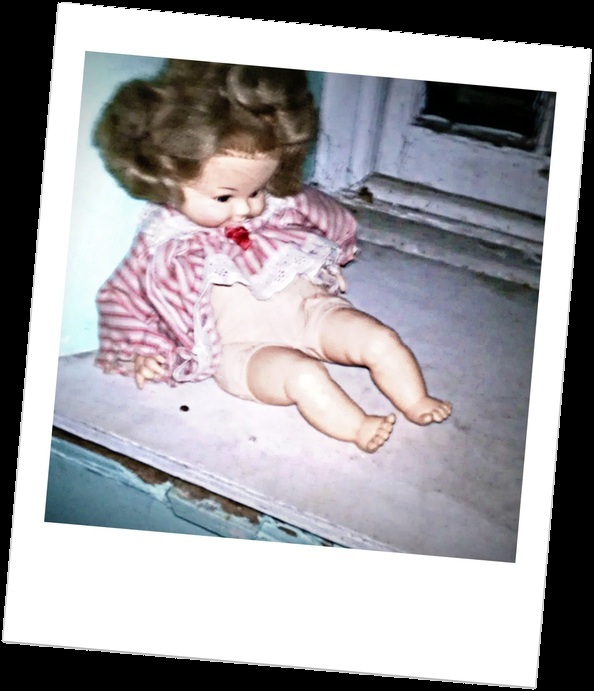

The first ghosts Sarah introduces to us are Lilly, Ruth, and Emily. Lilly and Emily are both little girls, and both—they say—will come out to play with lucky ghost hunters. Ruth is an old woman, and the only impairment we’re told about is that she was confined to a feeding chair, a sort of wheelchair with a tray attached to the front. The guide suggests that sometimes visitors hear the sound of it going up and down the halls. We’re told she’s protective of the child-ghosts. A domestic haunting. There are music boxes in the rooms both girls are said to haunt; the cheap reproductions every little girl has with the plastic ballerina en pointe twirling in the middle. In Lilly’s room, there is also a toy box full of cheap plastic toys, which our guide tells us have been brought and left for the girl-ghost by visitors. Someone in our crowd says, “Like she’d even know what to do with toys from the twentieth century.” I want to answer, “There were children here until 1994, as patients,” but I’m still trying to behave, to blend in, so I don’t. Instead, I ask Sarah, “Were these real patients here? Do you know when and why they were here?”

“We don’t talk about patient history,” Sarah tells me. “That’s not what people come here for. Even on the historical tour, we stick to talking about the building, about the treatments, and about some of the notable staff.”

The only other named ghost on the first two floors is Jacob, an alcoholic who responds well to being offered whiskey. Which, of course, we’ve been told it is against the rules for us to have. And maybe it really is, because although there are many moldering and melted pieces of candy on the windowsills of the girl ghost’s rooms, there are no half-full whiskey bottles in Jacob’s.

After about an hour of this, Sarah lets us loose on our own, allowing us to wander the entire building—save for a few rooms whose doors are locked because the floors have become unsafe—unescorted. The building is 242,000 square-feet; most of the time we are too far away from the other ghost hunters to even hear them.

“This is the part that feels really transgressive,” I say to Brad as we wander alone down a dark corridor. “It doesn’t seem like we should be allowed to do this.” I open the door to a large bathroom with several toilet stalls, baths, and sinks.

“Yeah,” Brad says. “But I guess there isn’t much we could do to the place.” He shines his flashlight into a pile of debris in the far corner of the hallway.

I step into the bathroom. “You know, I was always too afraid to do this as a kid,” I say and then look into the mirror. “Bloody Mary,” I say and then spin around. “Bloody Mary.” Spin. “Bloody Mary.” Spin. No apparition appears in the mirror. I knew it wouldn’t, but for a moment there had been a frisson of fear in my belly, an echo of a younger me who was capable of believing in ghosts.

What I Know of Madness 1

I am in an unlit room, sitting on a rocking chair in front of a barred window, looking out over a darkened lawn. I wear a white cotton nightgown with flocking around the banded collar, and hold my mother’s old porcelain doll—the one she named Baby Brother—in my arms. His skull is bald and crazed with age, the paint that gave detail to his face long ago rubbed away. I have wrapped him in a white blanket, and I am singing tunelessly to him while I rock.

In this dream, one I’ve had now and again for twenty years, a series of doctors come into the room and insist Baby Brother isn’t a real baby, that I must put him down and come away, and I will be locked in this room until I do. I both know and don’t know the doll is not a real baby. That it is not my baby. It doesn’t matter. The idea of letting him go is a searing pain across my chest. Each time they try to pry him from my arms, I want to scream, the pain so strong it takes my breath away. It is unbearable and I turn my head to look out into the starless night.

I want to say, “I know he isn’t real, and it doesn’t matter.” I want to say, “This isn’t something you could understand.” But I can’t, because every time they walk into the room they reach for the doll, and then I have no breath for words.

Asylum Visitors Leave Dolls for Lilly and Emily

What Lingers

For the first hour of the tour, I think that the most abject thing about the old hospital is that it still stinks of stale sweat and filthy bodies. But then we’re allowed to go off by ourselves, and the smell dies. When we get back together, I realize it’s one of the other tourists…a big guy in unwashed jeans who has been here before and who believes not only that there are ghosts here, but that he has a special ability to find with them. He calls himself a ghost hunter with pride, not irony.

The Lobotomy Recovery Ward

The lobotomy recovery ward is not on the walk-through of the first two floors that Sarah lead us on, but neither is it off limits, so we ask Copperhead to tell us how to find it. “I’ll walk you down,” he says. I try to ask him questions, but he’s got a salesman’s heavy handed way of answering that always turns the question back around to his own prowess as a ghost hunter. “We find the ghosts from talking to them, interacting with them, not by reading the records. But often, we can match the ghosts we find with someone in the actual patient registry. Like Jacob,” he says, referring to the one male ghost in the first two levels. “We found that there was in fact a Jacob here being treated for alcoholism, and that he was obsessed with talking about whiskey.” This is rural Appalachia. If there had never been a drunk named Jacob in treatment here during the more than 100 years the hospital operated, that would be the coincidence worth noting.

Lobotomies at Weston Hospital were most often performed by Dr. Walter Freeman, the doctor who “pioneered” the ice pick lobotomy. He traveled around the country in his personal van, which he called the lobotomobile, performing procedures at a number of institutions.

“When did they stop doing lobotomies here?” I ask Copperhead. A few yards ahead, he points to a plaque about Dr. Freeman, which says he performed his last lobotomy at Weston in 1967. “There, see, it says. 1967.” But I know this sign elides a more difficult truth. Dr. Freeman’s last lobotomy procedure at Weston was in 1967, but a I know a woman who was the lead nurse in the lobotomy recovery ward in the 1980s. I tell Copperhead this.

“That can’t be true,” he says, turning his back to me and walking on. “The sign says right there, the last one was done in 1967.”

Freeman was no longer performing the surgeries, but other physicians were. I don’t think Copperhead is lying, I just don’t think he knows very much about the actual history of the hospital. Or cares, and that troubles me more.

Brad and I have borrowed something called a “k2,” a meter that’s supposed to read electro-magnetic energy and thus identify the presence of ghosts. It looks like a television remote with no buttons; just a row of five lights: green, light green, yellow, orange, and red. Just what these lights mean is vague, except that the more of them that are lit up, the more it suggests the presence of a spirit. The whole time we’re in the lobotomy ward, all five of the lights on ours stay lit.

“What kind of activity do you get down here? Do the ghosts speak to you?” Brad asks Copperhead.

“No. I mean, these guys were pretty much brain-dead, so we don’t get much from them,” Copperhead says.

A Heart-Breaking Sign Over A Sink In the Children’s Ward

What I Know of Madness 2

In my dream, the bars on the window blur, and I stare beyond the darkened lawn to a row of Bald Cypress trees. These twisted giants shielded my childhood. I remember playing in their towering ranks, hiding with Felicity when we were still small enough to stand among their knees and not be seen.

I am not at Cypress Manor, although these are my grandfather’s trees and not simply the same kind. I don’t know how they have come to line the lawn of this sterile place, with its white blankets, white paint, and doctors in quiet white shoes. I’m not sure if the trees are meant to keep me safely here or mark the border to the place I could go if I would just put down the doll. It doesn’t matter.

I hold Baby Brother in my lap and stare out over the darkened lawn at the silhouettes of these magnificent trees until the doctors give up and leave the room. In the quiet, I weep at the sweetness of being among the cypress again, and now it’s the pain of their beauty that takes my breath away. I can’t imagine wanting to leave this place, to ever again live beyond the reach of their long shadows. I laugh at the doctors for threatening to keep me locked in. If they want the doll, they should threaten to throw the door open wide.

I rock the doll, my lips against the warm, downy skin of his scalp. He smells of sweet milk and talc. I hum the song of the wind in the boughs of the trees, rocking back and forth in rhythm with their gentle sway.

The One Story They Claim is True

“Dean,” Sarah says, “was a mute. This story, we can document. This one, we know is true. His roommates hung him from the ceiling with a bed sheet and beat him, beat him real bad. One of them realized that they were going to get in big trouble, so they decided they better kill him. Dean was unconscious, so they laid him on the floor and put the leg of one of the beds on his head. Then they jumped up and down on the bed until they had pulverized his skull.” She pauses for effect. “Then one of his two roommates ran down the hall to the nurse’s station and said that the ghost in this room had killed Dean. One of the men who did it, a man named Myers, just died at the new Sharpe state hospital a couple of weeks ago.

“When we first started coming through here, Dean was real friendly. He’d play with us and joke around. But over time, he got quieter and quieter until finally he just stopped interacting with us at all. We asked him if we’d hurt his feelings, or offended him. It took Copperhead a while to get him to talk to us, but finally he said no, we hadn’t hurt his feelings or anything. It was just hard for him to listen to us tell his story over and over again. So we asked if he wanted us to stop telling people his story. ‘No,’ he said. ‘I think it’s important for people to know my story. But could you tell it in the hallway so I don’t have to listen to it?’ And that,” says our guide, “is why we’re standing out here instead of in the room.”

Brad asks, “Does he communicate any differently with you than the other ghosts, since he couldn’t speak?”

“No, I don’t think so. What do you mean?” Sarah asks.

“Well, because he wasn’t able to talk in life. Like, how did he let you know that he didn’t want to listen to you tell his story anymore?”

Sarah is visibly flustered. “Well, Dean has never spoken directly to me. But I’m pretty sure Copperhead and some of the other ghost hunters were able to get his voice on EVP.” She explains that it’s a sort of tape recorder that can capture ghostly voices and make them audible to us.

I ask Sarah for the full name of Dean’s killer, the one who has just died, but she doesn’t know. Later, I ask Copperhead. “Michael David Myers,” he says. This is the name of the non-speaking serial killer who escapes from a psychiatric hospital to find and kill his sister (and a lot of other people) in the movie Halloween and its nine sequels.

Ghost Adventures

Zak, it turns out, is Zak Bagans, one of the hosts of the show Ghost Adventures. I find parts of a seven hour live broadcast they did on Halloween, 2009 on YouTube. A former employee of Weston Hospital talks about Ruth, remembers her as a violent old woman who would bang on the tray of her feeding chair whenever a man walked past.

Sarah had shown us the seclusion cells, told us that anyone could have a patient put in one, that patients sometimes stayed locked inside for months at a time. That some of them died. Near midnight, Zak locks three volunteers in the seclusion cells and then starts yelling at a ghost he believes has said “fuck you” to the ghost hunters. Nothing much happens. One girl says she felt something brush her hair, tug on her jacket. Zak calls out to the ghost he imagines is there, offering to keep the girl locked up in the seclusion cell for the rest of the night if he will only show himself.

I do a web search. Although fans have requested it, none of the many ghost hunting shows have ever gone to a concentration camp.

According to the Ghost Hunters, the “Orb” in this Photo I Took is a Spirit

What I know of Madness 3

A Story I Believe My Father Told Me Once, But That He Says I Made Up:

“I was in high school,” my father said, “and working in the afternoons, driving the truck to make deliveries for Dad.”

My grandfather was a grocery wholesaler. Not the grandfather whose cypress trees guarded my childhood, but my father’s father, who was the worst sort of bastard; mean and bigoted and dumb. Who never guarded anyone’s childhood.

“And I remember coming home from school. Mom was passed out drunk, and when Dad got home, he said, ‘I’m not doing it this time. Johnny, you’re going to have to take your mother up to the State Hospital. Just pull up and tell ‘em you’ve got Bonnie Einstein, they’ll know what to do with her. Lord knows they’ve seen her enough times before.’ And then Dad and I put her in the back of the truck, with all the empty pallets from the day’s delivery, and Dad went off to play golf.”

I think my father was drunk himself when he told me this story, in the first years of a decade-long bender that would end only when we, his adult children, committed him to a rehab facility. “I also had to go pick her up. Had to take her something to wear, because they just dumped the patients in these big wards, men and women together, and after not too long the clothes they were wearing when they were admitted would rot off their bodies. They didn’t give them hospital gowns or anything. Just left them in those big rooms, naked.”

Years later, when he tells me that I’ve made up this story, I don’t question him. I hated my grandmother—a mean old drunk with a sharp tongue and filthy mouth—and by then she’d been dead long enough that he’d taken to calling her my sainted mother. And he’s haunted enough without my insisting on seeing ghosts he doesn’t believe are there.

Sarah Einstein lives in Athens, OH where she is a PhD student in Creative Nonfiction at Ohio University. Her work has previously appeared in Ninth Letter, Fringe Magazine, PANK, and other journals, and has been awarded a Pushcart Prize. Her micro-collection, Remnants of Passion, is upcoming from Shebooks.

Read our interview with Sarah here.