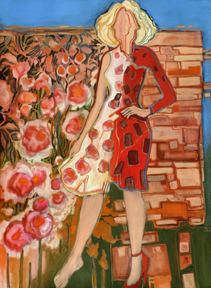

“Four Red Birds” by Marilyn Sears Bourbon

Roshani is going to be an oceanographer. Her mother tries to make sense of this career choice by telling relatives her daughter is going to college to be a scientist, and oh, look at the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico and how useful scientists are in that situation. It’s impressive enough that she managed to raise a child in war-torn Nepal – but to bring her to America and put her through college? That deserves some sort of Nobel Prize.

For the most part, Roshani lets her mother brag when the mood strikes because it doesn’t happen often. Usually she’s agonizing over how Roshani recently dyed her pitch-black hair with the slightest hue of red, or making wary comments about Roshani becoming “just another cushy, entitled American.” When they came to the US a few years ago, a school counselor recommended Roshani take anti-depressants for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and of course, when her mother saw the prescription in the medicine cabinet, she flared into laughter. “Are you serious? You don’t need drugs. These Americans just like to diagnose things.” Roshani watched as she flushed them down the toilet.

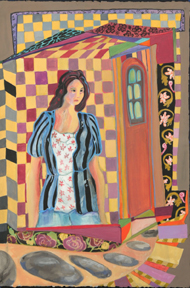

At the same time, her mother seems to have left their past in Nepal. She discourages talking about the day at the market when they saw those dead men, or the long bouts of depression her mother has suddenly shown since Roshani’s father left six months ago. Her black hair has grown unkempt, her body sagging like a frayed tapestry, her oval face—which once resembled Roshani’s—has thinned. The closest she ever came to explaining her overwhelming lethargy was, “Your father, he was usually the one I talked to.” Which leaves Roshani in some position of being the new source of comfort, a job she’s not even sure how to do for herself.

After her mother curls into bed tonight, Roshani slips into her tightest jeans and a shirt that shows just enough cleavage. She pokes her head in her mother’s doorway to wave goodbye and sees her swallowed by the striped comforter, her tulip eyes staring at the ceiling fan. She secretly wants her mother to order her to cover up some of that skin – anything that will indicate she’s seeing the world in front of her.

“I just have a little headache,” she says instead, but Roshani knows it’s something fiercer, more insidious, eating away at her. She’s too afraid to offer her company because she knows she’ll likely take her up on that offer.

“Sleep should help,” she offers. To her, sleep is the act of hushing all thoughts. She and her mother could dangle in nothingness like specks near the deepest ocean shelf. There, sunlight won’t penetrate and life forms numbly float, hoping to crash into an ally or a predator, anything that reminds them that they’re not alone down there.

Outside, Roshani’s date-of-the-week has been patiently waiting to take her to the other side of the Bronx where a small-time street race is happening. She slinks through the heavy summer night humidity to his Dodge Charger, and a burst of air conditioning hits her when she opens the door.

“Hey, Marcus,” she says. He looks slightly different than she remembers from when she gave him her number – more confident, perhaps. His face is strong, with a firm jaw and straight teeth. His eyes are a dark shade of brown, verging on black, and his hair is just long enough for her to let her fingers disappear into it. He’s listening to heavy Caribbean rap, the kind she likes to hear in clubs because the syncopated beat gets everyone moving as one glimmering mass, as if they’re all part of one big flock of birds.

“Damn, about time,” he says. His teasing has a biting undercurrent of impatience. “You ready now?”

“If you’re so tired of waiting, why are you talking instead of moving?” she returns with a smile, slightly taken aback by how unfiltered his tone is. She fingers the side of her seatbelt for a second then opts to leave it off. Speeding without it feels like freedom.

Marcus shrugs away her joke and pulls the car from the curb. Roshani takes a moment to convince herself she doesn’t like guys with a sense of humor anyway, that his impatience indicates a measure of depth and complexity. They met only a week ago at a mutual friend’s party, and they had exchanged looks – then a dance – then a kiss – then phone numbers. Despite their quick connection that night, the excitement of finally being alone together feels stale.

She tries to warm things up. “Are we stopping to grab some drinks?”

“Na, don’t have time,” he says, the irritation blatant this time. He then throws a smile in her direction as if to salvage the mood. “But after?”

“Sure.” She relaxes into the fat leather of the passenger seat. Her arms are folded against the blasting vents, her shirt too small to offer much warmth.

Marcus reaches to the stereo and turns the volume knob down. “So what do you want to talk about?”

The candid question is endearing, in a way. Roshani catches herself stroking the side of her cheek to keep from giggling uncomfortably, her fingers grazing the raised skin of a two-inch scar. She wants to say the right thing. Something interesting but not too personal. Something that will make him remember her when this night is over. Her mind scrambles desperately but comes back with nothing.

“I’ll talk about anything,” she replies, though this isn’t completely true. Thought after thought is discarded: her mother, following the hypnotizing circles of the ceiling fan. Her father, off with another woman, probably someone with soft curves and contagious laughter. Her old friends, still in Nepal, who have fallen completely out of touch.

She could talk about Nepal. About how she used to hide under her covers at night when the rebels spat out bullets or how her mother used to drive her to the market when curfew was lifted for a couple hours each day. One day her mother told Roshani to cover her eyes at the military checkpoint in the road, but she didn’t listen. Roshani opened her eyes too wide and saw men preparing to torch bodies with bloody pinholes punched through, the skin drained to the faded color of shale. It smelled like spoiled lamb and ash, and the hot acid of vomit had burned her throat while she tried to swallow it back down.

“Do you party a lot?” Marcus asks this halfheartedly.

Her mind snaps back to the cold car, Marcus’s indifferent silence. She wonders why his mood is so heavy, if it was something she said. “Once in a while. Do you?”

“Same.”

She fidgets with her hands, tries to find something to keep the silence from becoming too noticeable. Nothing. When she thinks of partying, she’s only brought back to a time before she came to America five years ago. Lately, as she fills out college applications and eats silent dinners with her mother, those are the only memories that matter. She thinks of how when she was twelve in Nepal, she and her neighborhood friends used to line up on a break wall and sip bottles of stolen malt liquor. They’d play balance games: try to walk the narrow strip of crumbling concrete without falling off. She’s not sure why she suddenly recognizes this memory with worry. They were only twelve years old; no one even suspected that alcohol would be on their breaths. Even though those moments already passed without injury, she fears that the children in those memories will unexpectedly stumble and fall off the wall, break the growing bones in their bodies, disfigure themselves.

Marcus and Roshani don’t speak until they get to the barricaded street, where several cars are lined up, their drivers clustering behind them. Marcus pulls up to a starting line of sorts and gets out. The goosebumps on Roshani’s body melt off when she exits the car, and she’s reminded that it’s summer.

Marcus tells her to “hang on” while he steps over to his friends. She leans against his car door as they greet each other, slap bets into firm palms, check out one guy’s new rims. They audibly tease him about being late – to which Marcus clicks his tongue apologetically, jerks his head in Roshani’s direction, and the other guys perceptively go, “Ohh.” It’s only a few minutes before he gets back, but by then, she has thought of something to say.

“How often do you race?”

“Every other week about,” he says.

She smiles. “Then I’m safe with you,” she says lightly.

“Safe?”

His look makes her feel like she’s chock-full of naïveté. She’s bothered for only a passing moment, and then she realizes she’d rather him think that than have her explain why she’s not naïve.

“The cops could bust this at any moment, and you call it safe?”

She shrugs casually and looks down at her shirt as she straightens the neckline. Marcus doesn’t watch; he goes to the other side of the Dodge and gets in to start it. His car purrs like a jungle cat, and Roshani gets in timidly.

She finds the courage to ask, “Something wrong?”

He throws her a look that seems to laugh at her. “I’m just focused on the race. You not enjoying yourself?”

“No, I’m good,” she says. “This is cool.”

Their surroundings are shaken by revving engines. Spectators are sprinkling the sidewalks. Some glance around nervously for flashing police lights, while others quietly study the drivers. Roshani feels misplaced in the passenger seat, as if she’s not supposed to be there. But isn’t this feeling familiar? Hasn’t she felt this way since leaving Nepal? No one ever told her where to be – she just ended up somewhere far away, where the only way to avoid danger is to keep moving, keep occupying herself. She doesn’t want to become like her mother, counting ceiling fan rotations. She wants Marcus to like her. She always wants her dates to like her, but something usually seems to be amiss. She’s narrowed the explanation down to this: she either shows too little or too much of herself.

Marcus is focusing on the road and moving his hands along the steering wheel as if rehearsing every turn. Roshani wonders why he brought her here. To impress her? To see how she’d react to this setting?

Someone waves a flag, Marcus punches the gas, and the car lurches forward. The streets have been scouted out and barricaded, and the four cars take full reign of the four open lanes. Their noses line up for a while, then one after another pulls ahead or drops behind.

Roshani can’t take her eyes off the speed limit. 70…75…80…85…90… The borough is blurring along East Fordham Road: away with abandoned apartment complexes, dimly-lit tattoo parlors, auto repair shops with faded signs. The street lights strobe in and out of the windows; the sheer force of velocity presses her back, wills her to be calm. She thinks of nothing but movement.

In a way, she expects the race to take her somewhere – a beautiful destination, perhaps. Something more than a finish line. But they pass another flag several minutes later, and it’s over. They come in third. Marcus slaps the dashboard but doesn’t say anything. He slows the car, and they’re soon like any other driver on the road. They have to clear out of the scene fast, settle their bets in a parking lot ten blocks away. Again, Roshani waits in the car as things are worked out between the racers.

When the lot clears, Marcus’s mood has changed. He turns to Roshani with new interest, a sudden focus. She can smell the ginger in his cologne. Something inside tells her this is the moment he’s ready to pretend he is interested in what she has to say. She is ready to let him.

“You smoke?” Marcus asks.

“Sometimes.”

Marcus immediately produces a small plastic film case containing weed and a square piece of paper. He rolls the joint like an expert. They light up, and her thoughts ping pong between fast and slow.

She finds herself leaning toward the windshield and looking up at the sky. In Nepal, the stars would stick out like a billion pin pricks in large, sweeping clusters. The Bronx is different. Everything is clouded, smogged-up, bloated with light so that she often forgets there are stars at all.

“What are you thinking about?” Marcus asks, studying her thin face, her wide-set eyes. As she avoids his gaze, she catches the sight of a stray cat creeping from house to house.

For a second, she lets herself sink into another memory of Nepal, of being five years old and watching her mom crack the neck of a chicken. She helped her pluck the feathers in fistfuls. She never imagined being here, with chickens already dead and plucked and stacked in grocery store refrigerators.

Marcus realizes she is clamming up, and he urges kindly, though in a somewhat jocular way, “You can tell me.”

Maybe it’s the weed, but she wants to trust him. She wants to tell him about her future in oceanography, about how she’s finally found something she understands. It comforts her about death, about how they are all just floating crustaceans suspended in slate-black depths of the ocean, and dying is like knocking into an anglerfish’s bioluminescent lantern. There is a magnificent wash of relief at finding a lambent orb of light, the type of relief that devastates the heart with too much happiness. Everyone feels this right before the giant jaws clamp over them, back into darkness, and truth is, in the scheme of things, barely anyone will notice they are gone.

Instead of saying this, she surprises herself. “Just this weird memory, something back in Nepal, where I’m from.”

“Tell me,” he says, though she feels he wouldn’t care either way.

Still, it’s been so long since she’s talked about Nepal with anyone. Her mother treats those memories like garage clutter she prefers to neither examine nor throw out. “I’m just remembering slaughtering a chicken,” she says, almost as if she’s confessing it.

Marcus scrunches his nose. “Why?”

Immediately, she’s angry she said this. She tries to shrug it off, but she doesn’t want to leave without an explanation. “Strange, right?” she tries to laugh, but it sounds unnatural. “I guess I’m just trying to find something beautiful in things.”

“There are plenty of beautiful things about you,” he says, not understanding. He smiles as if to charm her. “You have the prettiest smile I’ve seen in a long time.”

My smile? she wonders. The one with the two-inch scar curling up the side, the one she got from a piece of shrapnel in a bomb blast?

Marcus is just twisting words, but still she gives him credit for being there with her. She knows what he actually wants, so she gives it to him. She lets her dimples show and runs her hand up his thigh to his pants’ zipper, and he smiles back. She goes down on him with her eyes open, but she does not see, like sleepwalking. Being noticed in this moment is the farthest from being alone that she can be; it is the closest to healing she can imagine. Every time he sighs, he acknowledges her, that she’s giving him something perfect in this moment. She’s a frigid, floating crustacean, grasping for something warm to hold onto in metallic water.

When he finishes, Marcus offers to take her home. After giving him directions, she turns up the stereo to make the silence less noticeable. The car rips recklessly through the Bronx, hitting the staccato of potholes, speeding up for yellow lights. This night has given them all it has to offer; in that, she senses an undercurrent of urgency to end it.

When they pull up to her house, Marcus says, “See you around.”

“Yea,” she says, knowing the noncommittal insinuation of that statement.

When she gets inside, she goes to the sink and washes out her mouth with cold water. She wonders if her mother is still in bed. She goes to her to see if her headache has gone away or if she needs ibuprofen.

Her mother is curled up but not sleeping, her arms wrapping around her body to keep the world out or her soul in. The room has the deadweight heaviness of fatigue but the restless feeling of insomnia. Roshani forgets what she came to ask her and just stands in the doorway, adjacent to the dimmed lamp and the tissue-littered nightstand.

Her eyes are open, but she is not seeing. Roshani can tell she is still thinking, still churning her marriage over exhaustively like turning over couch cushions to find missing keys. Nothing was missing from you, she wants to say.

“Roshani.” Her voice is achy from crying. “What is this loneliness?”

The feeling she gets is bare-boned, as if something has been slowly scraping her raw for days, months, years. The man who helped raise her is gone, but it is worse for her mother. The man she loves, the man who held her during the hardest times, has left.

Roshani crawls onto the bed and lies down next to her, cradling her back into her chest like a shell. Her mother’s sobs crescendo, and Roshani squeezes her tighter to let her know she is there to take care of her, still love her. And together, they float into sleep.

Katherine Russell is a freelance writer and editor residing in Buffalo, NY. She’s currently working on finding an agent and publisher for her novel, Without Shame, which looks at the interactions between an American English teacher and pre-independent Bangladesh. She recently came out with a poetry chapbook called Shapes of Water, which chronicles “coming of age” with cystic fibrosis, a genetic lung disease. She maintains a blog for cystic fibrosis patients at www.lifewitheverybreath.com.

Read our interview with Katherine here.