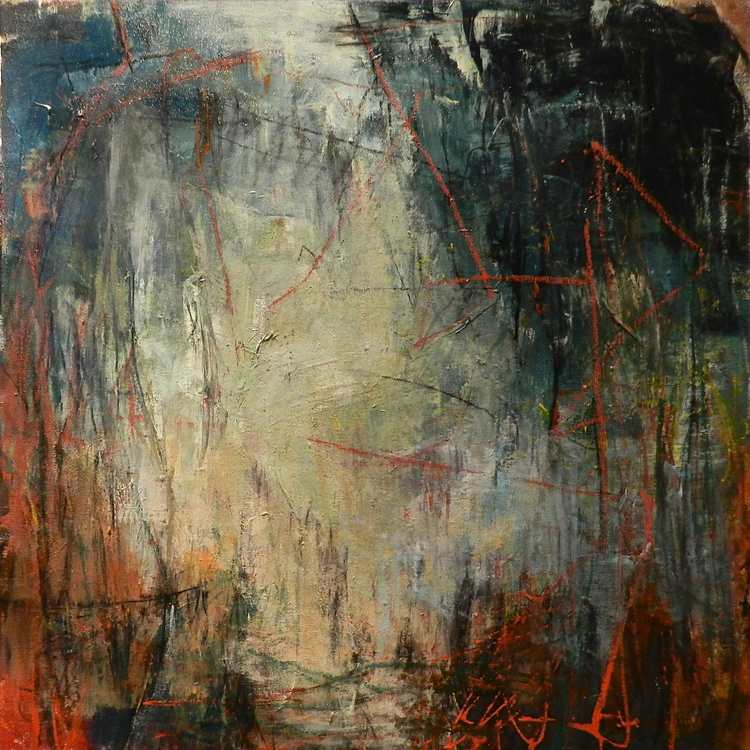

“Tomoka Trail” by Pat Zalisko, 24×24, acrylic, mixed media on canvas

Kimo and I stretched out long in my bed. I ran my finger over his arm wrapped around my waist. I traced the edges of the blotches on his skin, milky white patches blossoming against brown. “It’s what Michael Jackson said he had,” Kimo said when Kayla asked him what was up with his skin. I’d hushed her: That’s rude. But Kimo, he didn’t mind. “It’s just the way I am.” People call him Hapa Kimo. Hapa is what locals call folks who are half Caucasian and half something else. Half haole, half Japanese. Half haole, half Samoan. Kimo’s mom was haole, his dad Filipino. “Guess my skin wanted to keep Mom close by,” he said.

Kimo came by every Tuesday. It was the day he delivered bottled water to the Lawa‘i Valley. I once asked him if he had a woman for every day of the week, for every part of Kaua‘i. He laughed. “You’re crazy. You think they knockin’ down doors to get to Kimo?” I wasn’t sure what that said about me, or him. He also taught surf lessons and did handyman work. That’s how it is here: you have to work three jobs to get by. I only worked one, giving massages at a hotel spa, because John was paying enough child support for me and Kayla.

“Almost Kayla time,” Kimo said. I slid out from under his arm. We were always sure to make the bed back up by the time Kayla was home from school. Most days, my daughter came home covered in the island’s red dirt. It was on her ankles or her elbows, sometimes on her knees. When it got into her shorts and shirts, there was no cleaning it out. Kayla used to wear white, when we lived on the mainland. She had white dresses and frilly white tops; little white Capri pants and even white sandals. But since we moved to Kaua‘i last year there was no point. The island made its mark on everyone and everything.

Kimo and I sat on the porch, not saying much, just listening to the way the trade winds swished the palms, when Kayla came walking up the road in her shorts and T-shirt and flip-flops. Slippers, Mom, she always reminded me. That’s what they call them here.

“Howzit?” she said, plopping her backpack on the porch.

“Hey, little wahine,” Kimo said. “You ready to hit some waves?”

“I need a snack,” she said and headed inside.

“Little grind!” he called after her. “No want your stomach too full.”

I waited until Kayla was in the kitchen, away from us. “I’d like it if you didn’t talk Pidgin with her,” I said.

“That’s how people talk round here, Dorrie,” Kimo said, just looking out at the breeze, making me believe it was possible to see a breeze. “You been here long enough to know.”

Nine months. At first it didn’t take me long to slip into the island ways, the slow talk and the slow walking, slang that seemed easier than saying the real words. But after John left us, my attitude went back the other way.

“How about when she needs to get into college?” I asked. Or how about if we’re not forever stuck on this island? Someday we might just get back to the mainland, and kids would tease her.

“She’s twelve,” Kimo said. “Plenty of time till college.”

Kayla came back with a fruit roll-up in one hand, her surfboard tucked under the other arm. “Let’s rip,” she said. “You coming, Mom?”

“You bet.” There was no work that afternoon, no tourists wanting me to rub their muscles with coconut-scented oil. The three of us squeezed in the front seat of Kimo’s rusted pick-up and drove down the curving road to Po‘ipu.

~

When John and I moved to Kaua‘i we bought a small house in Kalaheo, in a valley away from Po‘ipu’s tourists and desert landscape. Kalaheo is carved out of jungle, blanketed by bamboo and monkeypod trees and philodendrons with leaves like giant flat fingers. On Po‘ipu’s south side, it’s just dry red dirt and cactus. It’s barren like the surface of Mars, except where a mainland developer came in and planted palm trees and thick-blade grass. Orchids, plumeria, yellow hibiscus. If you went the other direction from our house, you’d be in Waimea canyon, deep walls carved away by the river’s erosion. If you want something different on Kaua‘i, you don’t have to go far. John went North, to Leilani’s house. It’s rainier there, but greener, too.

Kimo and Kayla took to their boards, paddling out to waves. I sat on the beach with the tourists lazing in the sun. They bring that fake coconut smell with them, painting them slick and brown. When I was fifteen, sixteen, I’d sit in my backyard coated in baby oil, trying for a Valley Girl tan. I thought the burn would wear off into luscious brown. It never really happened that way, but I kept on burning my flesh anyway.

Kimo paddled ahead of Kayla, sometimes looking back for her. Little waves rolled towards them, and Kimo and Kayla slipped over the tops. Like riding a bucking bronco, but gentle. Sometimes a bigger wave came, but too close to the shore, so they grasped the front of their boards and dove under. “Always better to go under or over a wave than through it,” Kimo would say.

John didn’t want Kayla surfing, still wouldn’t want her surfing if he knew she surfed. “It’s too dangerous for a young girl,” he said. Kayla had been trying to wear him down since before we moved, since we were on the plane. She kept talking about a girl from Kaua‘i who lost her arm in a shark attack. “She started surfing again only one month after the shark bit her arm off,” Kayla said. “And she’s a professional now.” The argument did little to sway John, and who could blame him? But for every surfer who gets mauled in a shark attack there are hundreds of thousands who never do. John would never see it that way, but after he left us for Leilani, I figured how he saw things wasn’t the only way.

Kayla and Kimo were so far out that I couldn’t hear them, they couldn’t see me. Not that they were looking for me. I wondered why Kimo never had any kids of his own. Then again, I didn’t know that he didn’t. I didn’t even know if Kimo had ever been married. Hell, I didn’t know what he was doing with me, some uptight, middle-aged haole.

Kimo waved a windmill through the air at Kayla. Take this one. She paddled to catch the lip of the wave. Then she was up on her feet. Sometimes I imagined her on that board when I did Warrior Two in yoga. I’d imagine the salty spray around my face, a roar so loud I couldn’t hear. No mirrored walls in front of me, no click-click-click of the overhead fan, no rubber mat sticking me to the ground.

Her first few seconds upright were a fight between Kayla and the wave: who would ride who. She gave a good knee bend, and won that battle. The wave pulled her along, like she was tethered to the other end.

Whatever tension had been keeping Kayla upright was severed, and the water tunnel crashed down. I shielded my hands over my eyes, afternoon sun grimacing back at me. Kimo paddled toward where Kayla had gone down. Her yellow board popped up, and then her head. The ocean spit her right back out. Kimo held out his hand and pulled her on her board. The two paddled back out again. They went to fight another battle against the sea.

~

John had Kayla every other weekend, more if he wanted. There was no official custody agreement. That could have never happened on the mainland. John would have had one of the partners at his firm draw up reams of paperwork. Everything would have been official, from the separation to the division of assets to the final divorce. But after we moved to the islands, John lost that drive. Killer instinct, he used to call it.

Every Friday John drove clockwise around the island to pick up Kayla from my house. On Sundays, I drove counter-clockwise to retrieve her. His way was worse, getting choked in Friday rush hour in Lihu‘e. Nothing like L.A., of course. This traffic was just one long lane going one way, one long lane going another. When I drove up on Sunday, the worst of the traffic wasn’t in Lihu‘e, but up North. Tourists heading for Hanalei beaches and the Na Pali Coast. Pulling their cars aside to snap pictures of rainbows.

Leilani’s house was inland, surrounded by mango trees. “We eat a lot of mangos when I’m there,” Kayla told me. “Like, all the time. It drives me crazy.” I knew she just said this for me. Leilani’s three mangy dogs barked and followed my car up the long driveway to her house. Wagging tails, ears forward. No teeth bared.

“Are you early?” John was on the porch, wearing a shirt bursting with orange plumeria.

I looked at my watch. “Not really.”

“Kay, your mom’s here!” John yelled into the house. “Get your stuff together.”

“Yeah, coming!” my daughter yelled back.

John stood against the porch railing, looking out at the mangos like I wasn’t on the top step, my arms folded across my chest. “You want some tea?” he said. “Or juice? Hey, Leilani!” he called behind him. “What kind of juice do we have?”

“Why you yelling?” Leilani stepped through the front door wearing peach-colored scrubs. I couldn’t tell if she was coming from the hospital or going. “Hi, Dorrie.”

She wasn’t pretty like the word Leilani makes you think, long and thin, on an exotic postcard. But she wasn’t some big Samoan either, a formidable force of womanliness. She was an average woman. Except she was more.

“Bring some juice out,” John said. “We can sit, talk story.” It—talk story—sounded stupid coming out of John’s mouth. It’s what everyone said around here, Kimo all the time, Kayla, and even me, but from John it sounded like trying to force a round peg into a square hole.

“I’m not thirsty,” I said.

“Maybe some cookies, then?” John said.

“John, come inside,” Leilani said. He followed her in.

All the windows in Leilani’s wood house were open to capture whatever breeze made it that far inland. It also pushed out John and Leilani’s voices.

“What are you doing, trying to get us to all sit and grind?” she asked.

“There’s no reason we can’t be friendly,” John said.

“You left her for another woman,” Leilani said. “She doesn’t want to be your friend.”

“She’ll get over that,” John said. “She’ll move on.”

He didn’t know about me and Kimo. I didn’t want him to think I’d moved on.

“John, just let her be,” Leilani said. “Show her respect.”

It made me want to say, “Yeah, I’ll have some mango juice,” to sit on Leilani’s porch and eat coco-mac cookies, just to prove her wrong, because it pissed me off that she was right. But Kayla skipped through the front door, carrying her backpack and duffle bag. “Okay, Mom,” she said. “Let’s go.”

There was hardly any traffic on our side as we drove clockwise again. I’d gotten hungry, standing on that porch, so we stopped at a roadside stand in Anahola for burgers and shakes. We ate at a round picnic table with tourists. Two wild chickens and a rooster wandered around our perimeter, waiting for us to drop a piece of meat. The island was overrun with feral roosters, crowing day and night. We watched the birds scratch and scrape, waiting for their prey.

~

Next Tuesday, when we were still lying in bed, Kimo said, “Let’s you and me get some dinner on Saturday. While Kayla’s with her dad.”

“Why?” I asked. Kimo and I had never been outside of the house together, not unless we were at the beach with Kayla, getting shave ice, eating Puka Dogs.

Kimo pulled himself on top of me and kissed my lips. “If you’re this pretty in the daylight, you must be a goddess at night.”

There wasn’t much more to say, really.

~

We ate at a Chinese barbeque joint in Lihu‘e, but didn’t eat barbeque. There were too many places to get island barbeque, so we shared shrimp with choi sum and sizzling scallops with black bean sauce. Fried coconut ice cream for dessert. The place was full of brown-skinned locals, a few haole, like me, and some tourists brave enough to go off the beaten path. I kept thinking that most of those locals were technically hapa, but none of them looked hapa like Kimo. His brown and white skin, the way he didn’t care much about it, made him seem royal. Maybe Kimo was right, maybe there was something about seeing each other in nightlight that made us divine.

We went back to Kimo’s place, a house he shared with two other guys. One was tending bar, the other waiting tables. The living room furniture was worn wicker, dusty walls covered by tapestries of whales and sea turtles. The air smelled like old apple cider vinegar.

“It’s how locals live,” Kimo said, even though I’d said nothing. I got the feeling that he could read my thoughts. That maybe he had some sort of island mojo.

His bedroom was small, but immaculate. No clothes on the floor, no clutter on his nightstand. The bed made with crisp-looking sheets. His mattress sat on a bed frame of carved koa wood.

“It was my tutu’s,” he said, as I ran my hand over the reddish-brown wood. “She gave it to my dad, and my dad gave it to me.”

My grandmother gave me a brooch, once. It was gold-plated, shaped like a snowflake, mindlessly picked out of her jewelry box. Here, she’d said, you can have this. I lost it in the backseat of some guy’s car years ago.

Kimo’s bed was bigger than a back seat. We stretched out and up, laid flat and round. We bathed in the scent of plumeria and sex. We were royalty.

~

Next Tuesday I worked at the spa. Another massage therapist called in sick and I had to cover her shift. I don’t know if anyone really got sick—more likely someone was heading to big waves on the north shore. “Cough, cough,” they’d spew into the phone. “I have a sore throat.” It meant I wouldn’t see Kimo, but he was going to drop by the house and pick up Kayla for surfing anyway.

I gave massages to three couples that day, folks who just got married or wanted to pretend like they just did. Olina and I worked together, standing side by side in a thatched hale. Her hands glided over one client, mine over the other. We worked separate, but moved together. The rain beat outside.

Olina and I were standing outside the hale, waiting for the couple to put on their long terry robes. Rain smacked the tops of broad leaf plants, then slid into the garden. There was water from the waterfalls, water from the sky. When it rained like this, it was easy to believe the island would just return to the ocean.

“So, I hear you were out with Hapa Kimo the other night,” Olina said.

“Where did you hear that?”

She waved a hand. “Oh, you know how people talk. Nothin’ better to do.”

“We had scallops,” I said.

“Just scallops, yeah?” she poked me in the ribs. If Olina knew that Kimo and I had Chinese BBQ in Lihu‘e, then could the news travel to John? Sure, it was an island of fifty-thousand people, but only fifty miles of road between us. Maybe there was some math, some physics, some law that made information travel faster. Then John would think it was okay, dragging me and Kayla all the way across the ocean, only to leave us amid giant leaves for mango trees.

“Hey, Dorrie?” It was the receptionist who stood behind the spa’s front desk looking impossibly pretty. “Phone call for you. Says it’s an emergency. About your daughter.”

All the smells and sounds of the island shut down. I could have been on the surface of Mars, ice cold and airless.

~

Kayla was at Mahelona Memorial Hospital in Kapa‘a. She got hit by a big wave, and then another, and she couldn’t grab her board. The waves kept coming, and one finally threw her into the rocks. Ancient lava, black and jagged, tearing into my baby girl’s skull. She was bleeding in the brain, needed surgery to stop it. I signed the papers, called John. Waited for him to show.

I sat next to Kimo in the waiting room. His hair was still wet. “Why is she here?” I asked.

He put his hand on top of mine, but I refused to give him a hand. Just a fist, so his hand was more like a piece of paper in rock, paper, scissors. “I know. It’s hard to understand.”

“No,” I said, pulling my fist away from him. “Why the fuck is she here? On this part of the island? Why were you surfing up North?”

“She wanted to surf where Bethany surfed,” he said.

“You mean where Bethany got her arm bitten off by a shark?”

“That’s not what happened,” Kimo said gently.

“I know what happened.” I stood. “You took my daughter someplace dangerous. You let her do something that could kill her.”

“Dorrie . . . .” Kimo reached up, pulled my hand. “She’s going to be fine. She’ll be fine.”

Kimo didn’t know if Kayla would be fine. I didn’t know it, John didn’t know it, and Leilani didn’t know it either. Even if Kayla was fine, John would be pissed. Pissed enough to take Kayla away from me.

Leilani walked around the corner, just wearing shorts and a T-shirt, like it was any old day. “John’s on his way,” she said. “Had his phone turned off. Just got the message.”

“Have you checked on Kayla yet?” I asked. “How is she?”

“The surgery’s coming along,” Leilani said. “Right now she’s okay.” Then Leilani turned to Kimo. “You have that looked at yet?”

“No time,” Kimo said and touched his head. I didn’t see them before, the scrapes and scratches on his forehead and his arm. Red bleeding into the borders of his brown and the white.

She said something in Tagalog, and he said something back that I couldn’t understand. She stood at Kimo’s side, peeked closely at his skull.

Kimo put Kayla in the ocean, and Kimo pulled her out. But it didn’t feel like a zero-sum game. Especially since I knew John could turn back to his killer-instinct ways. If he took Kayla away, I’d have no reason to stay. But I still couldn’t go back to the mainland, where plants were small and turned brown and dry. I’d stay here, alone, just for those two weekends a month when I could drive counter-clockwise for my daughter. I’d be stuck with half of me on one side of the island, half of me on the other.

The elevator bell dinged down the hall. I waited for a doctor or a nurse to deliver the news. I waited for a priest to take my hands. I waited for John to be harried and irate. I waited for John to punch out Kimo. I waited for John to take Kayla away. I waited to be expelled from this uncertain paradise. I waited for my daughter, dressed in bright white.

Liz Prato is the author of Baby’s On Fire: Stories (Press 53) from which this story is reprinted. Her stories and essays have appeared in numerous journals, including Hayden’s Ferry Review, Iron Horse Literary Review, The Rumpus, Hunger Mountain, The Butter, and Subtropics. She is Editor-at-Large for Forest Avenue Press, and teaches at literary festivals across the country. Liz is currently working on an essay collection that examines her decades-long relationship with Hawai‘i, using the prism of White colonialism.

Read an interview with Liz here.