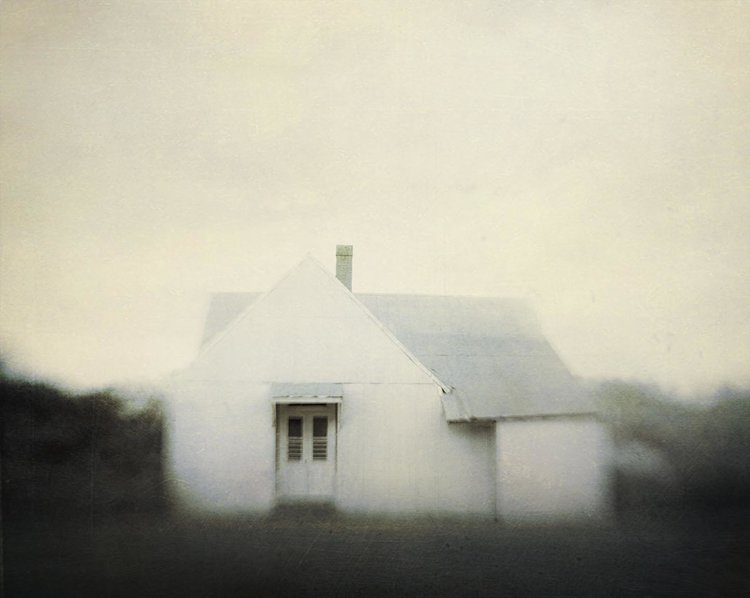

“What We Leave Behind,” Image by Dawn Surratt.

(See also “Those Who Once Lived There Return” by Wendy Miles.)

When my fifth grade English teacher, Mr. Garabedian, asked me to stand, the room went suddenly quiet and still. Everyone in the class turned their attention to me, and holding my breath, I stood wondering why I had been singled out. Was I in some kind of trouble, and if so, what had I done wrong?

Mr. Garabedian handed me the homework assignment I’d given him the previous day. “I’d like Margaret to read her poem.” My class had recently begun studying poetry, and this poem was our first homework assignment. “Live from the Bijoux Theatre,” Mr. G. said with a swish of his arm, pausing dramatically, theatrically, and drawing out the syllables of my name, “Maaaaargaret Maaaaaginnis.”

I confess to finding this kind of attention slightly intoxicating. I wanted more of moments such as this, and I’d read and write anything he wanted in exchange. Modeling my teacher’s behavior, I silently summoned what was dramatic and theatrical in me, and read,

I watch the waves roll out to sea,

and wonder what the ocean thinks of me

in my faded rolled up jeans

and a beach hat ripping at the seams.

“A beach hat ripping at the seams?” my father said. “Where did you get that idea?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t know where it came from.” I didn’t even have a beach hat. The poem was about me and not about me. My father asked if the ocean represented God.

“I don’t know what it represents,” I said. “Maybe it’s you.”

He laughed. “Maybe.”

Maybe it did represent him; maybe everything represented him—the waves, the sea, the ocean, the faded jeans, and the beach hat ripped at the seams. Or maybe I sought to represent not my father but myself in that which was faded and ripped and alone in the cold vastness of the ocean. It was hard sometimes to distinguish where he ended and I began, that is if he ever really ended, and if I ever really began. I’ve spent my life trying to discern this.

The night I’d written the poem had been a typical Saturday night at my house, everyone in bed except me. As usual, I had been waiting up for my father to come from his AA meeting since for me there was no sleep until my father was safely home. As a young child, I used to keep my mother company while she waited. We would sit huddled together on the couch with only the glow from the TV illuminating the darkness. This had been our nightly ritual for years, but at some point she stopped waiting. I cannot say exactly when or why she stopped, all I know is that I am forever alone at that kitchen table, either reading or writing, forever ten, forever reading Judy Blume and rereading Laura Ingalls Wilder, learning from them what I could not learn in a house where the deepest and truest thoughts and emotions had been relegated to the realm of the Unspoken. Before Mr. G.’s poetry lessons, I read as I waited, raising my head from the pages before me whenever I thought I heard my father’s car in the driveway. After the poetry lessons, I would write while waiting for my father’s return. Thirty years later, I’m a light and restless sleeper, part of me waiting for a car that will never come again.

The night I wrote that first poem for Mr. G., my father had come home. I’d read the poem to him, delighting in the expression on his face—the soft glow in his eyes, the gentleness of his smile. He had this peculiar way of looking at me in the dim kitchen light, staring really, as if he were seeing me for the first time, or the last. It’s hard to know. This look haunted me then, and haunts me now. This look was one of the reasons I couldn’t go to bed until he came home. Every time he left the house, I was afraid I’d never see him again. But this night the look had a little something different in it, and he said softly, “It’s a very good poem, Margaret.” Margaret. He always called me by name. “Maybe you’ll be a writer someday.”

~

I cannot remember which came first, fifth grade or that little pink hardcover book on my mother’s nightstand. Fifth grade memories of Mr. G. and his poetry writing lessons are among my most vivid; they appear fully rendered in the florescent light of my fifth-grade classroom. The pink hardcover, however, is a dimmer memory that flickers in the shadow of a bedside reading lamp my mother seldom turned on—she was too busy, too anxious, too preoccupied to read to me or my younger sister. My father was the reader, disappearing for hours with a book or two, reappearing in time to read something to my sister or me. Yet it was on my mother’s nightstand I found the little pink book of poems. I picked it up. The cover was shiny and smooth as were the pages. I wasn’t supposed to be in my parents’ room if one of them wasn’t there. I was snooping. I was a snooper, my nana, with whom we lived, used to say, whenever she caught me rummaging through drawers, cupboards, and armoires. I didn’t call it snooping; I called it searching. I was searching for all that went unspoken in our house.

I stood alone on my mother’s side of the room, transfixed by my latest discovery, slowly turning the smooth pages of the book. I don’t remember the book’s title or anything I read on those pages except for the poem:

Though my soul may set in darkness,

It will rise in perfect light.

I have loved the stars too fondly

To be fearful of the night.~ an old astronomer to his pupil

The child I was had not yet imagined that a poem, someone else’s words on paper, could articulate my feelings before I myself could, but the minute I read these words I knew it was true.

~

When my father was a boy of sixteen, his sister Margaret died when the passenger door of a girlfriend’s car opened and Margaret fell out, hitting her head against a guardrail. She died on impact they said, which was supposed to make everyone feel better. Who would want to consider Margaret lying in the road, half-alive, waiting while a friend ran to someone’s house to call an ambulance? Because she died on impact, she did not have to endure death’s cliché, watching scenes from her life as she began to die, seeing things she never wanted to see again. She was just eighteen. How much of life existed beyond the family parameter? Not much. It’s the pain and disappointment she’d see again as she tells her parents she’s leaving home. She cannot live with such anger and resentment; she cannot watch them further destroy each other; she cannot watch as her brother’s pain turns to self-destructive rage. She never asked to be the favored child. She didn’t ask to be spared. She would have traded places with him. That’s how much she loved him. She is dying in the street and the memory of her brother’s detached vacant stare makes her shudder. Her last thoughts will be of him. What kind of man will he become? She thinks she sees him approaching and dies straining for his hand.

But this is not what happened. Margaret died on impact. But my father had been approaching her. He reached across death for her and kept reaching for the rest of his life, and this is what I heard in his voice, every time he said my name.

At the end of the fifth grade, I wrote a poem about my aunt and wanted to present it to my father as a gift. But I showed my mother first, sensing on some level the significance of her role the Keeper of the Unspoken. I found her in the upstairs hallway. Because I interrupted her sweeping, she barely read the poem before she handed it back to me, but she’d read enough to say, “Hide that, Margaret, or throw it away. Please don’t show your father.”

My hands trembled as I folded the poem, but my eyes remained dry. I swallowed the lump of tears in my throat. I wouldn’t disobey my mother, not in that moment, because I didn’t want to upset my father, and clearly my mother thought I would if I showed my poem to him. So, I tucked the folded poem in a drawer and didn’t look at it again. I cannot remember what I wrote in that lost poem, but I must admit that I’ve been trying to recapture it for thirty years. It grieves me that I never showed the poem to my father. Never told him that his pain was mine.

~

In a somewhat passionate burst of inspiration, I wrote another poem for my father. This time, however, I didn’t go to my mother with it first. I was twelve now. I didn’t want to hear that I couldn’t or shouldn’t show my father. I didn’t want to relegate the poem or my feelings to the back of the dresser drawer, where they would lay tucked under scarves or underwear, seemingly forgotten. I titled my poem “The Last Time I Saw Paris” after the 1954 film that had inspired it. The film starred Elizabeth Taylor and Van Johnson as Helen and Charles Wills, the tragically flawed and ill-fated main characters of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story “Babylon Revisited.” Child actor Sandy Deschner played the couple’s young daughter, who lived with her aunt and uncle after her mother’s death. Charles has returned to Paris to reclaim his daughter and make peace with his memories. I cannot say with whom I identified more: Charles, Helen, or their daughter, who was called Vicki in the film and Honoria in Fitzgerald’s story.

At age twelve, I hadn’t heard of Fitzgerald or his celebrated story, but years later, as an undergraduate English Literature major, the story had left me weeping over the bible-thin pages of my Norton Anthology. My grief was raw and real: two years prior to reading “Babylon Revisited,” my father had succumbed to his Unspoken, ultimately taking his own life.

I cannot say which precise moment in the film provided the inspiration that made me run for a pencil and paper, or if there wasn’t one at all; maybe it was the story itself that moved me, a story of grief and regret and recklessness and love, the kind of love that manages to grow in the midst of such suffering. Though the daughter clearly loved her mother, she thrived on her father’s love and attention; here was her source of joy. Twenty-eight years later, I do not remember the poem in its entirety, but I recall the first stanza:

The last time I saw Paris,

I was free and young at heart.

I didn’t even think of us

As so very far apart.

I don’t know where my mother was, but I found my father in bed with a book propped open across his chest. I handed him the poem and he read it, and then asked if I would read it to him. Then he asked if he could keep the poem. Of course, he could, it was his. “Thank you. I’ll treasure it,” he said, and at his words, I felt a palpable joy. In that moment of shared words and feelings, my life made sense. My father folded the poem and tucked it in the top drawer of his bureau. When my parents weren’t home, I used to go into their room and open my father’s drawer to make sure the poem was still there. Every time I saw it lying there in the drawer, I remembered the passion I felt in the classroom and the passion in that burst of inspiration. I remembered the joy and pleasure I felt sharing my words with my father, such deep satisfaction, the writing itself an act of defiance in the face of the Unspoken.

Margaret MacInnis’ essays have appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, Brevity, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Gettysburg Review, Gulf Coast, River Teeth, Tampa Review, and other literary magazine and journals. Her work has been distinguished by Best American Essays (Notable Distinction 2007, 2009, 2011) and Best American Nonrequired Reading series (Notable Distinction 2009), and is anthologized in the 2015 Love & Profanity and the 2009 River Teeth Reader. She lives in Iowa City with her partner, Ryan, and their daughter, Lila. Since 2010, she has worked as personal assistant to Marilynne Robinson, American novelist and essayist.

This piece first appeared in The Briar Cliff Review