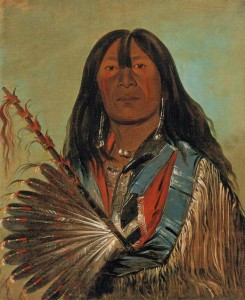

“Collecting the Wild I” by Suzanne Stryk

Looking back through the history of poetry, many of our great writers have been described as haunted (Coleridge, Berryman, Plath, etc). If not haunted by actual ghosts (or witches or demons or God), they were at least haunted by their own desires, contradictions, inconsistencies, successes, and failures.

Haunted poems (whether or not they are written by haunted poets) fuse with our imagination and become something well beyond the sum of their parts. But how does one define hauntedness as it relates to poetry and language? What’s the difference between a poem we read and like and one that becomes fused with our imagination in a way that unsettles and prods and cajoles us? How does the transference happen? How does a poet connect with his or her reader in this intense way? Is there some key to making a poem more haunted? Ambiguity? A missing puzzle piece? Automatic writing?

To explore these questions, we’ll examine a few works for their hauntedness and see if the ghosts of these poems translate into something we can use in our own work—something useful to “haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights.”

First, I’d like to propose and consider a few definitions. Hauntedness is the manifestation of the thing behind the poem (or poet) that makes it impossible, that makes writing a poem a nearly supernatural act. (By impossible I mean something like: irreducible to a set of articulable, rational gestures, motifs, or reproducible machine parts.)

Hauntedness is the most important, unsayable, unpinnable (to the butterfly wall) piece of what relates the poem to the poet. It is “that quality of witnessing something that eludes description— glimpses, the idea of seeing something elliptically,” says poet Matthew Guenette, and he believes childhood memories are a good example: “…one kid hitting another with a brick; something dangerous ducking in and out of the trees in the woods across the road; a ghostly reflection in the windows on my mother’s porch a few weeks after my stepfather’s death.”

So hauntedness in literature could be the perceptible presence of an absence, the Frankensteined breath in the poem’s structure that leads us to its ontology, the metaphysical building blocks of its reality, the ghost in the machinery that makes it alive.

“Hauntedness,” says poet Nick Sturm, is the “breath of life behind the words.” It is the witch behind the craft. Robert Bly, in his essay, “A Wrong Turning in American Poetry,” puts it this way, “A human body, just dead, is very like a living body except that it no longer contains something that was invisible anyway. In a poem, as in a human body, what is invisible makes all the difference. The presence of poetry in words is extremely mysterious.”

We can’t get to the invisible foundation of being, which is why we need poems in the first place. With poetry we have to fill in the blanks and imagine new ones. We have to “live in the gaps and walk or dance along the cliff edge in the dark” (Alexis Orgera).

As writers—working and reworking the same subject, the same form, the same set of aesthetic concerns—we never quite get to the meaning deferred, never quite say it right or exhaust its possibilities.

The really interesting thing about this sort of failure is that it’s existential. Trying over and over again to say the unsayable is a clear indication that we aren’t dead. I write, therefore I am. I read the same poem for the two hundredth time, and even though I’m unsettled by it, even though I never quite get it, my failure—the missing piece of the puzzle, the mystery, the disquietude— points the way toward a next time. I begin again. I’m in shock or in awe. I am ALIVE! Poems that boil down to a clearly connected set of finely machined parts aren’t nearly as interesting. As Dean Young puts it, “[In poetry] We’re trying to make birds, not birdhouses.” So as readers and writers we’re trying to get at what animates the bird, the music in its heart.

Hauntedness ranges backward into the past and forward into the future. I am the ghost of my own future self—and eventually the self that was and is no more. Time passes, life happens, we get old. The owl comes to take us. The house settles in an inexplicable way. No more dog. To be haunted, then, is a quality of existence, since as far as I can tell, the dead don’t haunt the dead, only the living. Therefore, if you’re haunted by something, you’re still breathing. It’s one of the ways of being sure you’re still not NOT (at least not in any significant sense), because you have a consciousness, a “you” to write home to.

~

A man has reached middle age when he is haunted by his youth and also by his death.

~

As poets we have an opportunity to capitalize on both the loss of the past and the dread of the future, as a way to turn both into something cathartic and hopeful in the present. But hauntedness is the unsettling quality of all this, our recognition that life, meaning, the whole wild mess of nonlinear, non-rational bullshit is impossibly irresolvable.

Of all the poems I’ve read and liked, perhaps 50 have become fused with my imagination, entangled with my life, my writing, and my teaching to the point that they define me in ways that I probably couldn’t identify or explain. How does such a transference of spirit—an entangledness of writer, poem, and reader—occur? It occurs in defiance of rational thought, of our knowing better—or knowing at all.

The poems that stick with us are the ones we never entirely figure out. They are unsettling and electrifying. They radiate, rather than delineate, meaning. At the heart of every haunted poem is a mysterious something, a living, strange and unfathomable—even supernatural—secret. Their energy never dissipates, and they come to resemble not just poems, but POETRY.

POETRY: the language of ghosts that activates and conjures the ancestry of words via non- rational imaginative play, music, association, and rule breaking. This galvanization of the otherworldliness of language is the spirit of what we do as writers and what we encounter and hold onto as readers.

~

To write a powerful poem is to cast a powerful spell, and to read one is to come under its influence, to be haunted by its charms and/or its curses. Poems catch us with the incantatory witchiness of words, of sound as much as sense. “The slightest loss of attention leads to death,” said Frank O’Hara. And yet, as readers and writers, what a thrill to be so taken. The suspense is killing me. Let’s look at a poem.

ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA

by Noelle Kocot

Here in this room I slept in

As you lay dead and alone

After you died, while I, superstitious

Peasant, slept, slept through

Phone call after phone call from

Detective after detective, finally

Waking to Daniel’s simple and beatific

Damon’s dead, and me waking up

Lizzette, breaking the news,

Making arrangements like a cop

Or fireman, taking a few minutes

To say I love you to the morning sky,

I still have never let anyone see me cry.

Never having been one of the fully

Living, I live, half of me in

A cornfield filled with skyscrapers,

Half of me in that place we are

Before we’re born and after we die.

Tonight I was outside thinking

Of that holy drunken terror

Jackson Pollock. Fuck you, moon,

He’d shout and cry. A big dog

Came running up to me and his owner

Shouted, Jackson, come back here.

You my teacher, died unknown

And there’s nothing for me to do

About it right now except to write

Your legacy no matter how inept

I can be. My phone rings.

I slide across pink ice to get it.

The splotched cat returns home.

When I asked you for a sign,

The fireplace doors shattered.

You are a dead musician who died

Alone. I wait to go to you,

Smoking and breaking curses under

The Jackson Pollock fuck you moon.

In this poem, Kocot recounts the moment of being told about the death of her husband, the composer Damon Tomblin (who died tragically, unexpectedly, in 2004). The thing that’s striking immediately here, beyond the explicit absence present in the memory of her loss, is the presence of the absence of togetherness via Death, the great separator, “Here in this room I slept in/as you lay dead and alone/After you died, while I, superstitious/ Peasant slept through/Phone call after phone call.”

When she finally wakes, “to Daniel’s simple and beatific/Damon’s dead” her world has changed, and she breaks “the news” to others, as later in the poem she smokes and breaks “curses.” To wake up alone, a widow, is for Kocot to suddenly live as torn apart, “half of me in a cornfield filled with skyscrapers,/Half of me in that place we are/Before we’re born and after we die.” And there the surreal collision/juxtaposition of the rural and urban landscape is compared and contrasted with a sort of liminal in-between-ness. Before we’re born and after we die is significantly nowhere. Kocot relates the experience of being everywhere and nowhere, at once.

Everything is connected—even her thoughts of Jackson Pollock to a dog named Jackson that just happens to run to her as she’s thinking about the artist, and later her sliding “across pink ice” to answer the phone (now an echo of the previous call, the only one that will ever matter, the one that changed her world permanently). Kocot is haunted by her own life in the face of Damon’s death. The thing she longs for isn’t to bring him back from the dead (she’s too smart for that); what she longs for is her own death. “Damon’s dead” and “I wait” to go to him beneath a “Jackson Pollock Fuck you moon.”

That ending (like all endings) is haunted. Endings mark the conclusion of something—“that’s all there is and there ain’t no more.” Is the “Fuck you moon” full and round or a middle finger sliver? And what of the notoriously cantankerous painter having, as it were, the last word of the poem, after muscling his way in via the speaker’s thoughts, and then eerily, coincidentally embodied in the body of a runaway dog? Yeah, this poem ends badly, beautifully. It’s an elegy— a tragedy—presided over by an angry-artist-moon.

Poetry often operates on the basis of malfunction. The poet misuses language extraordinarily— associatively, connotatively, figuratively—to create aesthetic affect, to cast (or be cast within) a magic spell of words—where meaning exists in metaphorical/imagistic terms.

~

Translations are haunted by their originals.

~

Every word is haunted by its own etymology. Its historical origins linger connotatively. These origins color the atmosphere of the language while remaining largely invisible. One doesn’t need to know, for example, that the word “haunt” derives from an old Norse word heimta meaning “to lead home, to frequent,” and yet these meanings are present in contemporary usage as a trace, an echo, a ghost. Every word is haunted by its past uses, and is also itself a haunting, a visit from the past into the present.

Poems deploy, destabilize, and explode the meaning(fullness) of language, creating fields of connotation, ambiguity, and metaphor, while playing on the history of words in the service of multiple possibilities. These are the ghosts of every line, every sentence.

Words are also haunted by other words, which in turn are haunted by still other words, and all of them are haunted by other languages, and language is haunted by human utterance as longing (a desire to meaningfully mean). This is art.

Words can even be haunted from the inside in ways other than connotation or etymology, for example: the “hunted” in “haunted,” the “error” in “terror,” the “owl” in “bowl” in “fowl,” even the “beasts” in “breasts.” This inner machinery of language becomes part of its associative atmosphere. Which leads me to…

A MOWN LAWN

by Lydia Davis

She hated a mown lawn. Maybe that was because mow was the reverse of wom, the beginning of the name of what she was—a woman. A mown lawn had a sad sound to it, like a long moan. From her, a mown lawn made a long moan. Lawn had some of the letters of man, though the reverse of man would be Nam, a bad war. A raw war. Lawn also contained the letters of law. In fact, lawn was a contraction of lawman. Certainly a lawman could and did mow a lawn. Law and order could be seen as starting from lawn order, valued by so many Americans. More lawn could be made using a lawn mower. A lawn mower did make more lawn. More lawn was a contraction of more lawmen. Did more lawn in America make more lawmen in America? Did more lawn make more Nam? More mown lawn made more long moan, from her. Or a lawn mourn. So often, she said, Americans wanted more mown lawn. All of American might be one long mown lawn. A lawn not mown grows long, she said: better a long lawn. Better a long lawn and a mole. Let the lawman have the mown lawn, she said. Or the moron, the lawn moron.

In this piece, Davis unpacks the associative etymology of a “mown lawn” via anagrammatic play and wild association, reminding us in the process (because process is often more important to Davis than narrative, character, scene, etc.) that well-groomed tidiness may be a front for the absence of substance. What haunts the ghostly narrator is pretense and the image, presented by a well-kempt, mown lawn, that all is well. The surfaces (as many American suburbs and the dysfunctional inhabitants therein attest) aren’t a reflection of the depths, or a reflection of anything at all. Davis’s lightly heavy-hearted critique of good clean American values suggests that good clean American values are often a series of moronic postures, a wasteland of appearances masquerading as success, prosperity, equality, and good neighborliness. The lawns are mown. To mow is to moan.

What Davis sees in the phrase “mown lawn” is the presence of possibility, a series of shadows in the grass of language itself—ones that can be sussed out by moving the furniture around, exposing all the dust bunnies.

~

Words on the page are haunted by the margins, by the periphery, by white space.

To be a poet is to tap into the shadow sides of us: obsession, memory, habit, personal history, value, belief, DNA.

The spirit comes rushing through the doorway into our hearts. In the beginning was the word. It’s all contained in the words.

The opposite of hauntedness is sobriety.

~

There is a concept called “poetic dictation” which Jack Spicer wrote about in the 1960s that posited (essentially) that anyone writing really good poems is merely a receiver, a medium, taking down as best as he or she can transmissions from what Spicer referred to variously as spooks, ghosts, and Martians. As he put it “[In poetry] …we are crystal sets, at best.” This reference to the old do-it-yourself crystal radio kits implies that poets need only tune into the invisible static and interference of the universe and take down whatever is overheard. Poems, it implies, don’t come from inside the poet, but from outside. The great aesthetic crisis, then, becomes how to capture as accurately as possible what those spooks, ghosts, and Martians are trying to tell us.

A related and more useful notion is the idea that sometimes one has to get out of the way of the poem—to pay attention to what it wants and needs to be rather than what we want it to be. Practically speaking, this is a matter of seeing where the poem leads us in the process of writing as opposed to sitting down to write a poem about grandmother’s sock drawer, the metaphorical meaningfulness of peonies, or paradise lost. One way to write a poem is to look inside yourself; another is to listen with your face against the ether. Both prospects seem pretty terrifying. In one you hear voices; in the other you have to make them up.

~

To be haunted is to be entangled with an image, idea or event so completely that one is transformed—imaginatively rewired to it and through it. The demonstration of the inherent hauntedness of language is (capital P) Poetry.

Hauntedness occurs (and reoccurs) at the level of the word, the poem, the writer and the reader. “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Even form is haunted and enlivened by its previous uses.

Imagine Ted Berrigan’s masterpiece The Sonnets without the sonnets of Shakespeare, Sidney, Keats, and others that came before it. The family tree of the sonnet—its ancestry—haunts Berrigan’s every word. And, weirdly enough, now Berrigan’s sonnets haunt (and inform our reading of) Shakespeare, Sidney, Keats and others.

~

The opposite of hauntedness is Wordsworth.

~

Literature is full of haunted and haunting people, places, /images, and ideas. They stick to us like a second, inspiriting skin and reoccur at the strangest times, in the most unpredictable ways, often when we’re “alone with the alone” as James Tate might say (and did say, but I don’t remember where—it haunts me).

Hauntedness relies on memory, especially memories that are fundamentally traumatic or mysterious in terms of what they mean in relation to who we are in the present. Haunting memories are shifty, significantly insensible, irreducible, and indelible. To be haunted is to be forced to confront again and again an impossible-to-make-sense-of image imaginatively. Logic fails us. We are haunted.

I SEE A LILY ON THY BROW

by Dean Young

It is 1816 and you gash your hand unloading

a crate of geese, but if you keep working

you’ll be able to buy a bucket of beer

with your potatoes. You’re probably 14 although

no one knows for sure and the whore you sometimes

sleep with could be your younger sister

and when your hand throbs to twice its size

turning the fingernails green, she knots

a poultice of mustard and turkey grease

but the next morning, you wake to a yellow

world and stumble through the London streets

until your head implodes like a suffocated

fire stuffing your nose with rancid smoke.

Somehow you’re removed to Guy’s Infirmary.

It’s Tuesday. The surgeon will demonstrate

on Wednesday and you’re the demonstration.

Five guzzles of brandy then they hoist you

into the theater, into the trapped drone

and humid scuffle, the throng of students

a single body staked with a thousand peering

bulbs and the doctor begins to saw. Of course

you’ll die in a week, suppurating on a camphor-

soaked sheet but now you scream and scream

plash in a red river, in a sulfuric steam

But above you, the assistant holding you down,

trying to fix you with sad, electric eyes

is John Keats.

“I See a Lily on Thy Brow” is one of the most haunting poems I know. It is written in second person, and essentially begins with “you” in 1816 getting a “gash in your hand unloading/ a crate of geese.” But you have to keep working, because, the poem tells us, you’re poor and fourteen, and as a result the gash becomes infected and eventually gangrenous and so needs to be amputated if you’re to have any hope of surviving.

This poem graphically depicts the squalid living (and dying) conditions of the poor during the industrial revolution, and it is also a reference to and a reminder of the fact that John Keats was a student of medicine, studying to be a surgeon, and part of his training was as a surgical assistant at Guy’s Infirmary in London. “I See a Lily on Thy Brow” isn’t really about “you” at all, nor your soon-to-be phantom limb, but about Keats’ poetic sensitivity and sensibility. The speaker is unflinchingly, clinically descriptive until the doctor starts to saw, at which point we are rushed forward into the shock and awe of irreparable loss.

Poems remind us of things we’ve lost and of how lost (and sometimes found) we are. As Young notes in his brilliant discourse on poetics The Art of Recklessness, “The highest accomplishment of human consciousness is the imagination and the highest accomplishment of the imagination is empathy.” Through empathy we find our feet with the world, connecting the self to the other viscerally, “suppurating on a camphor-/soaked sheet […]/plash in a red river of sulfuric steam.”

In the end, what the poem says more than anything else is that John Keats was a human being capable of intense feeling and sensitivity, including pain, suffering, love and all the rest of it— which is to say that the poem, like a lot of poems, is a little (history) lesson about our common humanity that comes to us via the demonstration (on Wednesday) of a poignant series of disconnections (the limb from the body, the poet from the surgeon, 2013 from 1816, me from you and you from me and Dean Young from John Keats!). The poem operates on us literally, palpably—to make red life stream in our veins—without the benefit of anesthesia.

~

Phantom limbs:

~

THIS LIVING HAND, NOW WARM AND CAPABLE

by John Keats

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d–see here it is–

I hold it towards you.

John Keats wrote two of the weirdest poems in existence in his “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” (The beautiful woman without mercy—which is where Dean Young’s title “I See a Lily on Thy Brow” comes from: “I see a lily on thy brow,/With anguish moist and fever dew;/And on thy cheek a fading rose/Fast withereth too.). Most scholars now believe that Keats never intended for “This Living Hand” to be a complete poem. As a result, our reading is haunted not only by our not knowing what Keats intended for the piece—since most of the time we don’t really know what an author’s intention is—but also by our deliberate persistence in reading “This Living Hand” as one of Keats’ truly haunting later works. Every reading we give it is a mistake.

Which isn’t to say that we shouldn’t read “This Living Hand” as a poem, only that when we do we’re probably bringing more to it—investing it with more sad electricity—than Keats ever did. To him it seems the poem was a body part—a fragment—a disembodied reaching hand— a monument to the witchery of poetry. The poem is a testament to both the alchemical ability of poetry to change language into life, experience, and feeling and to the idea that the best poems are the result of that quality in any great artist. Keats referred to it as Negative Capability (which, funny enough, might also be a mistake): “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact or reason.” No matter what Keats intended, we are fortunate to have the power of “This Living Hand” to haunt our days and chill our dreaming nights.

~

Hauntedness is hiddenness. It requires that we be in the dark about something—that we remain unable to resolve the phenomenon or experience that unsettles us. Something hidden is potentially terrifying, because we can’t attend to it—can’t plan for it. Poems that haunt us often create a situation or an atmosphere of hiddenness, a sense that the most important thing is not in the poem, but hovering in the atmosphere of connotation and possibility created by the language beyond the page.

THE FEAR

by Robert Frost

In Frost’s poem “The Fear” from his 1914 book North of Boston, he hides almost everything, ratcheting up the poem’s tension and strange ghostliness to a Twilight Zone pitch. He provides only enough narrative puzzle pieces to make us wonder what the hell is going on, but not enough to give us a clear sense of the various characters, their motives or the reason for their strange behavior. As a result, we make assumptions about both the couple who are the poem’s protagonists and the man from nowhere wanting “nothing” who is (potentially) the poem’s antagonist. The facts don’t add up—not for the reader or the characters. To further confuse us, Frost drops in odd details—suggestive, but ambiguous—and casts them in shadow and darkness. The only light in the poem comes from a lantern, which in the end clatters and goes out, leaving the woman (and the reader) alone in the dark.

In “The Fear,” Frost has provided the basic plot of a thousand slasher movies: couple shows up at old abandoned farmhouse in the middle of nowhere; psychopath appears and kills everyone. As the drama unfolds, one gets the sense that there’s a lot the poem isn’t telling us, and it’s exactly this withholding of information that gives the poem its terrifying, eerie power.

What is the “business” the woman alludes to? Who is the “he” that she implies has come to spy on them or sent someone else to watch? The paranoia becomes palpable. And yet, why is the woman so anxious for Joel to “go in—please”? Is the couple having an affair? Is the woman trying to escape an abusive relationship? Joel could be her brother. We only know that the woman and Joel seem very nervous about being found out. And what happens to Joel in the end? Where does he suddenly disappear to, and why does the woman drop the lantern?

We can make guesses, but the poem is unresolvable. Essentially Frost creates a dramatic abstraction, a gauzy scene reduced to an outline—a paper yet to be written, a lecture yet to be given—which is terrifying. It’s quite literally a ghost (of a) story, disguised as a poem.

~

A poem without a ghost is a dead poem, or even worse it’s just the facts. Just the facts: (Are there are ever just facts)? What use are bald facts in literature? One is always looking for what’s more than meets the eye. Perhaps I’m being prescriptive. I like puzzles—ones with missing pieces, ones I can’t figure out.

~

And now, to end things—and why here?—when this could go on, and happily ever after. To live “happily ever after” is also an ending—a presence becoming an absence. Sometimes it stays there, hanging in the air and thus becomes a haunting thing. Sometimes it goes into the void, which isn’t very happy at all.

~

In this case, “The End” is to stop typing or talking, to undo this voice (whatever it is) using language in a living way to make of it an object, a trace of what was, a sound fading out completely, or, if I’m lucky, expanding forever exponentially.

~

“The End” precedes a ghost, so I avoid it. “Parting is such sweet sorrow” etc. Also scary: the soul/mind from the body.

~

A longing is always haunted. Unrequited is always haunted.

~

“A lack long after”—Pianos Become the Teeth

~

“(now again)”—Sappho

~

So an ending is always a haunting thing in that it stops something breathing and makes of it a corpse. It’s an event, one worth mourning and celebrating. And while it’s true that endings often make way for new beginnings, they also allow the dust to settle. We get to remember and re- imagine what has already been (but which isn’t any longer) and to wonder where it’s gone, to consider what it points to, and to sometimes, nevertheless (never-the-less), be startled by the feeling of its absence as a presence.

~

Now. What can we make of the dust?

Matt Hart is the author of four books of poems, Who’s Who Vivid, Wolf Face, Light-Headed, and Sermons and Lectures Both Blank and Relentless, as well as several chapbooks. A fifth collection, Debacle Debacle, is forthcoming from H_NGM_N BKS. His poems, reviews, and essays have appeared in numerous journals, including Big Bell, Cincinnati Review, Coldfront, Columbia Poetry Review, Harvard Review, jubilat, Lungfull!, and Post Road. His awards include a Pushcart Prize and fellowships from both the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the Warren Wilson College MFA Program for Writers. A co-founder and the editor-in-chief of Forklift, Ohio: A Journal of Poetry, Cooking & Light Industrial Safety, he lives in Cincinnati where he teaches at the Art Academy of Cincinnati and plays in the band TRAVEL.

Read a conversation with Matt Hart here.