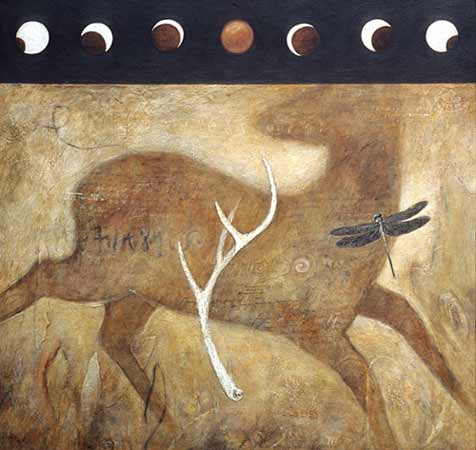

“Eclipse” by Suzanne Stryk 1998

Prologue

The last time I served on a jury was in 1977. I was an alternate. For two weeks I drove to felony court in Harvey, Illinois and listened to testimony in the case of the State of Illinois v. Melvin Thigpen. Mr. Thigpen was charged with abducting a high school girl from cheerleading practice, driving her out into the country, where she was raped, thrown into a ditch and shot three times.

The state laid out their evidence. For two days we heard testimony from police, evidence technicians, and medical professionals. Some of the witnesses were clear and precise, others fumbling and inarticulate. The evidence was delivered without emotion or drama. On the third day we heard from Carly Simmons. She was the victim.

Carly was poised and soft-spoken, but her voice carried, perhaps because it was so quiet in the courtroom. She had given the police artist a detailed description of her assailant. The sketch that the artist created bore a striking resemblance to Mr. Thigpen.

Carly described how she had been grabbed in her high school’s parking lot, held at gunpoint, and driven off into the country. She described the nubby texture of the car’s upholstery and the paisley pattern of her assailant’s nylon shirt. She explained in extreme detail how she was raped and then dragged from the car and thrown into a ten-foot drainage ditch. As she lay in the muddy ditch, she heard a gunshot and felt a burning sensation in her side. Then two more shots. One bullet hit her in the thigh and one grazed her neck. She played dead, and after several seconds she heard the car door slam and the sound of spitting gravel as her attacker drove off.

When she had finished testifying, the State’s Attorney asked if the assailant was in the courtroom. Carly looked at the defense table, raised her arm, and pointed to Mr. Thigpen. Her face betrayed neither anger, nor hate. She was not afraid. She was serene, triumphant. She had survived and now she had her day in court. That was thirty-five years ago.

The next five days of the trial were taken up with procedural arguments and we spent much of the time in the jury room, not discussing the case. The defense took one day to present their case and we listened to impassioned closing arguments by both sides before the judge gave us his instructions. The jury was escorted back to the jury room and I, as an alternate, was sent home, like one of those Survivor contestants who don’t make the grade.

The next day I called Ron, the foreman of the jury and an insurance adjustor for Allstate who I had lunched with on several occasions during procedurals. He told me it had taken them three hours to find Melvin Thigpen guilty on all charges. There had been no dissent among the jurors, except towards Ron who insisted they go through all the evidence before they voted.

For weeks I checked out the local news to see if there was a report on Thigpen’s sentence, but there was none. I figured I would never learn what happen to Melvin Thigpen.

Ten years later I was reading an article in The Wall Street Journal on career-development in prison. In their lead they featured an inmate in the Joliet Correctional Facility named Melvin Thigpen, who was serving fifteen to twenty years for rape. The Journal writer reported that Mr. Thigpen had become an accomplished watercolor artist.

Jury Duty – The Notice

Last month I received a notice from the court that I had been selected for jury duty again. In the intervening years I had been called several times, but was never needed. Just as well. I had bought an engine remanufacturing business in Arizona, which consumed all my time. It would have been difficult to be stuck on a jury for two weeks.

But my work schedule these days is more flexible and I wouldn’t mind serving on a jury in Skokie or even in the Loop. The notice indicates I’ve been drafted for criminal court on the southwest side, thirty miles from home. When I call in the day before, a recording tells me that if my last name starts with the letter D through M, then they want me. So I cancel my Friday activities – spin class and a personal training workout – and figure out when I need to leave the house to make it to the courtroom by 9:30 a.m.

The Questionnaire

Jury notice includes a questionnaire, which we are to fill out and bring with us. They want to know such things as age, occupation, marital status, age of children, whether we have ever been convicted of a crime, or been a party to a lawsuit, or whether we have any family in law enforcement. And the last question is whether we or any member of our family has been a victim of a crime. I have to think about that.

When I had the business in Phoenix, we were the victims of crime every week. Our plant was in a rough industrial neighborhood. Scavengers would scale the razor-wire fence and dump our valuable engine cores so they could steal the wood pallets. Most of our employees were honest, but like any business, a small percentage was not. Our trusted core buyer embezzled $50,000 and one of our financial managers falsified borrowing certificates.

Those weren’t trivial offenses, but they are nearly forgotten. What I remember from those fifteen years is the murder of Alma Hernandez.

Alma was eighteen years old. She had just started working for us as a piston installer. One day in August her ex-boyfriend came by during the morning break and asked to see her. When she met him in the parking lot in front of our office he shot her in the head and then made an insincere effort to shoot himself, but missed. One of the customer service reps rushed to Alma’s aid, but she died before the paramedics arrived. There were over a hundred employees at Alma’s funeral.

I know it was Alma and her family who were the victims of that crime, but her murder touched everyone in the company. Even so, I decide it doesn’t qualify as a crime against me or my family so I check the “No” box.

The Commute

There are six million people between me and the Criminal Court building. Half of them are on Interstate 94. It’s a one-hour drive if I leave at 6 am, but then I’d get there before the building opens. I roll out of my driveway at 7:30. It takes ninety minutes, but I’m sitting in the Jury room by 9:10. I’m the third juror to arrive. The lady at the front table takes my questionnaire and hands me a sheet of paper identifying me as part of Panel 3. I take a seat in the back behind the vending machines, next to the window.

The Vending Machine Challenge

I’m ten feet from the coffee machine. I know the coffee will suck, but it smells really good. The machine is complicated. There are different sizes and the usual choice of sugar or cream-like substance or decaffeination. There are a bunch of options for flavoring the coffee with hazelnut or maple or chocolate so it won’t taste so bad. I just want black. The coffee is hot.

A few minutes later, a stout black woman, who has squeezed into jeans several sizes too small, approaches the snack machine. She stares at the selection of chips and cookies and candy and looks very confused. Finally she turns and mumbles something at the professional-dressed young lady who is tapping on her laptop at the table next to me. The woman stops tapping, but doesn’t look up. “I don’t know,” she says. She sounds unnecessarily harsh, and maybe she realizes that because then she adds, “Sorry,” but the other woman has already turned back to the machine.

I look for someplace to perch my coffee so I can help her, but then I hear the sound of Doritos falling from their hook into the bottom of the machine. Vending success achieved, the woman ambles back to her seat.

The New Yorker

I have two dozen unread novels on my Kindle and I’ve brought five magazines, The Wall Street Journal, and the Chicago Tribune. I could be sequestered for a year and not run out of stuff to read. All I really need is The New Yorker. It has everything. I always check out the short story first. As I’m thumbing through to the story, I see an article about a convicted hit man serving a sixty-year sentence.

It’s a typical New Yorker feature. About twice as long as it needs to be, but fascinating. The hit man is candid with the reporter. He describes his crimes in great detail. He worked for drug dealers who hired him to kill other drug dealers. He just walks up and shoots them. Several times. Other than the fact that he has committed, by his count, a dozen murders, he seems like a nice guy. Good family man. Doesn’t do drugs or alcohol. Loyal to his wife. Devoted to his five-year-old daughter.

The Call

At 11 a.m., a young man in a wrinkled suit stands at the front of the room. He delivers a speech that sounds memorized. He thanks us for showing up and plays a video about what to expect if we are called for a trial. My panel is called. They line us up in two rows, like a kindergarten class, but instead of marching us to our courtroom we are told to go to lunch and report back at 12:45.

Act of Kindness #1

I opt for the cafeteria on the second floor, grab a roast beef sandwich, chips, and a lemonade. The woman from the vending machine is two ahead of me in line. She has eight dollars’ worth of food and hands the cashier four crumbled one-dollar bills. The cashier, a pleasant-faced white-haired lady tells her she needs more money, but the woman just frowns, confused. The cashier hesitates, then smiles and waves her on through. She tells her she will take care of it, but the woman doesn’t hear her.

Act of Kindness #2

The lady in front of me gives the cashier an extra dollar. “For that woman’s bill. That was a very nice thing you did,” she says. The cashier thanks her.

The Courtroom

After lunch we’re escorted to Courtroom 206. It looks like a small chapel, with stone walls and windows on the west side. It’s bright and cold and the acoustics are bad. The judge tells us we have been called to serve as jurors in the trial of William Bancroft and Ronnie Washington. The two men have been charged with first-degree murder. The judge explains that Mr. Washington will have his own jury, but for some of the testimony both juries will be present.

The judge introduces the bailiff, the court clerk, the stenographer and the three state’s attorneys – two men and a woman. The judge introduces Mr. Bancroft and his two attorneys. The defendant, when introduced, turns to the jurors (we’re seated in the gallery) and says, “Good afternoon.” He’s a young black man. Good looking and fit. He wears a dark suit with a white shirt and tie. He looks more professional than the two male state’s attorneys, who both have a stubby, rumpled Chicago-pol look. Actually, he looks a little bit like the hit man in The New Yorker article.

Bancroft’s lead attorney looks like Linda Hunt, the diminutive actress who plays the boss on NCIS: Los Angeles. Hunt always plays smart characters and I find myself thinking that Bancroft has a good lawyer.

The Judge

The judge is affable and also sort of rumpled, but robed, which helps. He acknowledges the room’s poor acoustics, then does nothing to help us hear him better. He talks fast and has an unusual cadence so it’s hard to realize he’s asking us a question until he finishes and says, “Anybody have a problem with that? Okay, no hands, no questions. Moving on.”

He asks us to stand to be sworn in. A juror raises his hand. Glasses, salt and pepper short-cropped hair. Earnest. Sort of a bookkeeper look. “Your honor, no disrespect, but I can’t take an oath.”

The judge sighs. “Can you affirm?”

The man repeats that he can’t take an oath.

“Whatever,” the judge says. He is clearly annoyed, but moves on to his next order of business, which is the pep talk.

The Two Brians

The judge tells us a story about two Brians. One, we’ve heard of, Brian Urlacher, and one we’ve never heard of, Brian Anderson. Long story short, one day the judge is watching television and sees Brian Anderson get off a plane returning from Iraq. He’s a triple amputee and his message is, “Life is good.” The judge tells us if Brian Anderson, with all he has endured, can have that kind of attitude, then we jurors have no reason to complain about the inconvenience of spending a week on jury duty.

It’s a good point. Perhaps he might try to slant it a little more positively. After all, none of us have complained or raised any problems (other than the guy who can’t take an oath). It takes the judge ten minutes to tell us the story. When he finishes I’m still waiting to learn what happened to Brian Urlacher. I decide not to ask.

The Lottery

There are sixty jurors in the two panels. The judge shuffles the questionnaires and picks fourteen. I’m the third juror called. There are eleven women and three men. When the recording asked only for jurors with last names from D to M, I wondered how that might affect the jury pool. None of those great Chicago names that start with Z or W or X are in our pool. But the fourteen of us called are a cross-section of Chicagoland. We are Irish, Polish, Lithuanian, Black, East Indian, Hispanic; employed, unemployed, retired; a tattooed biker, a white suburban dude (that would be me), a PTA lady, an insurance adjuster, and a legitimate blonde babe wearing tight-fitting jeans with lots of holes in the thighs.

The judge interviews each candidate. If we are married, he wants to know our spouse’s occupation. If we have married children he wants to know what their spouses do. He asks what we watch on television, how we get our news and what we read. No one has been the victim of a serious crime, although the biker had a cousin murdered twenty years ago.

The judge asks me what kind of work I do. I tell him I’m a writer. I figure this is not the time to share my angst over whether I should call myself a writer or say that I’m TRYING to be a writer. He asks me what I write and I tell him I’ve written a novel about a minor league baseball player. He asks me who it is, and then he says, “Wait, you said it was fiction. Never mind.” So I miss the opportunity to plug my book. Then he asks me what I’ve been reading. I suppose technically I should reveal that I’ve been reading about the hit man from Detroit who looks like the defendant. But I don’t. I just say fiction and the judge moves on.

The woman who had trouble at the vending machine is one of the fourteen selected. He asks her if she has ever been on a jury. She huffs something that sounds like it might be yes. He asks her if she reached a verdict. She doesn’t say anything. He frowns at her for upsetting his timetable. “Did you listen to testimony and decide whether the defendant was guilty or innocent?” She still doesn’t say anything. Finally he concludes she was just in the panel but had not been selected. I think he’s probably right, because I can’t imagine anyone accepting her as a juror.

We are given a ten-minute break while the judge and the attorneys go into his chambers to discuss us.

Thirty minutes later we’re back in the jury box waiting for the judge and lawyers to emerge from the judge’s chambers. The judge instructs us to follow the clerk to the jury room and says the clerk will read a list of those who will be given a check and dismissed. Those not called should report back to the courtroom at 10 a.m. on Tuesday to begin the trial of Mr. Bancroft.

My guess is they will keep everyone except the biker, vending machine lady, the black woman who said she read the bible every night, and maybe the Indian woman who ran the mini-mart with her husband.

Biker dude is the first name called. He smiles and wishes us all a happy week as he takes his check. The next name called is the blonde with the nice jeans. I have to admit I’m a little disappointed—she could make a good character if I write a story about this experience. The bible-reader goes next. And then the clerk calls my name. She hands me a check for $17.20. I feel like I’ve been fired. Vending machine lady makes the cut.

I am disappointed, but after two hours in bumper-to-bumper traffic on I-94, I start to feel a vague sense of relief. Someone – from the defense or the prosecution – decided I wasn’t a good choice to sit in judgment of William Bancroft.

I think they’re right.

Len Joy lives in Evanston, Illinois. His novel, “American Jukebox,” about a minor league baseball player whose life unravels after he fails to make it to the major leagues, will be published by Hark! New Era Publishing in 2013. His blog, “Do Not Go Gentle…” chronicles his pursuit of USA Triathlon Age-Group Championships. In June 2012 he completed his first Ironman at Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

**Note: All the names were changed, except for Melvin Thigpen’s.

Read an interview with Len here.