My second husband left me when I brought home an adopted three-hour-old daughter. A male colleague asked, “Were you raised to be independent?” I answered yes, though the thought was buried in my subconscious. The biological mother took the baby back, and I kept teaching.

My second husband left me when I brought home an adopted three-hour-old daughter. A male colleague asked, “Were you raised to be independent?” I answered yes, though the thought was buried in my subconscious. The biological mother took the baby back, and I kept teaching.

When I was hired to teach at The Hockaday School, a girls’ school founded in 1913, the headmaster said, “Kay is a role model for our students.” I’d lived in Viêt-Nam where my husband Jon was a pilot for Air America, a subsidiary of the CIA. Jon was killed flying in Laos. I returned to Dallas, a widow with PTSD, and began teaching at Hockaday in 1973. No one knew I lived with PTSD. No one knew I’d suffered a nervous breakdown. No one knew I was learning disabled. No one knew I’d washed sheets in a bathtub and ridden buses in Bangkok, burned a body in a Buddhist funeral, snorkeled off Con Son Island near the Tiger Cages, witnessed Vietnamese strippers dancing in my dining room for my husband’s Captain’s Party.

In 1970 no one knew about PTSD. Gold Star Families weren’t yet created. Nevertheless, my stomach kept hurting, I froze whenever sirens screamed and ambulances and fire trucks drove by. Once a tornado siren was wailing, and I stood frozen on the sidewalk until a neighbor took me by the hand and led me to safety. My internist kept testing me for Asian bugs and found nothing. I finally did biofeedback and starting writing. I had Agent Orange on my legs, my nerves were shattered. After the nervous breakdown my junior year at TCU, I had my father’s words seared in my brain: The first one is free. The second one they cancel your insurance. My psychiatrist lessons apply today: 1.Learn to say no. 2. Tea Kettle Theory: Let off steam. 3. Ladies don’t have much fun.

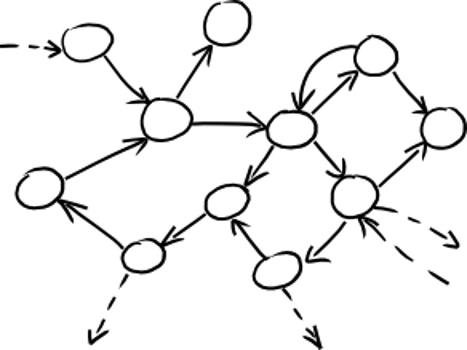

At school, I found a mentor, the lesbian English Department Chair, who suggested we read WOMEN WHO RUN WITH THE WOLVES (Clarissa Pinkoa Estes). “Be wild; that is how to clear the river.” No encouragement needed. War is fun—unless you get killed. THEY PUT ON MASKS (Byrd Baylor) explained to my sixth-grade students that we separate ourselves with masks of makeup, clothes, cars, religion, politics. I knew about masks. While teaching English to Middle School girls, I defended my thesis and published THE CONSTITUTION OF ADVANCED OBJECTS: A THEORY AND APPLICATION. Reading T.S. Eliot, W.V. Quine, and Melanie Klein, I created a reading paradigm to teach reading using objects viewed in a circular direction rather than in the traditional Fictean graph. Reading with a learning disability is an arduous task. I read from object to object, stringing leitmotif “beads” on a necklace, the topic sentence wrapping with the concluding sentence, as James Joyce FINNEGANS WAKE—

A way a lone a last loved a long the

wraps back to the beginning—the piano recital and the forgotten notes—the nervous breakdown—Jon’s death.

A last loved a lone.

A journey back to Southeast Asia

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s

from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of

recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

I gain entry to an hermeneutically sealed text—a Gadamerian notion in Quinean terms—by viewing the writing as a seamless web of objects.

Another faculty mentor twenty years my senior gave me a poster with these words—

Writing is easy: You just open your veins and let the blood drip out.

This mentor helped me apply for a grant and attend my first Writing Project. “Enjoy the journey on the ‘write’ track” became my motto: WRITE is displayed on my Texas license plate. My unpublished novel titled Z.O.S., “Zone of Silence,” the acronym for the CIA’s subsidiary, is a personal mantra. I write to know how I feel. I write to quiet my anxieties. I write to keep depression at bay. I write to come home to the Texas red dirt.

Thai temple rubbings Jon made were stolen. Letters of his were lost. I feared one day nothing would be left of my husband. “Painting the Elephant Gold,” originally a haibun—a writing combination of prose and haiku—wrote itself when I dropped the ceramic elephant purchased from Udorn Thailand days following Jon’s death. After being shipped around the world, residing in multiple apartments and homes, moving the elephant one night, my treasure crashed into pieces at my feet. I glued the pottery back together, painted it gold, and wrote the pain away. Kintsugi—like my life—gluing heart break together with American blood and Asian gold.

–Kay Merkel Boruff @KayMerkelBoruff http://www.writeink.org

Deep water!

Pingback: “Painting the Elephant Gold” by Kay Merkel Boruff | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal