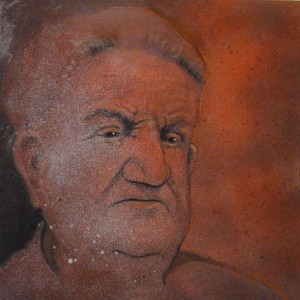

“Who Will Build the City Up Each Time?” by Elizabeth Leader, Acrylic & spray paint with recycled wood

Please, folks. Please, if you’ll only grant me a moment, I can straighten this whole mess out.

The man in Room 12 is my grandfather. I’m Terry’s youngest grandson, Donal Bradley. I live over in London. I came in Tuesday, and since visiting hours finish by—what time is it now? 2am—seriously? That’s… that’s later than I thought. My point is this: I’m a daytime visitor, so you wouldn’t necessarily know me.

Terry practically raised us after Dad died. When we were kids, I was his favourite. Kick the ball around on Sunday mornings; down to Cork Con after mass; drive back through Cobh, cast off from the pier. Terry’s boy, I was. But I grew, and the years passed, and we stretched far apart. Stretched thin. Finola gave him great-grandchildren, and of course, Susan took the teaching job here. And what was I? An investment banker with JP Morgan won’t hold a candle to the Headmistress of Castlegyleen Primary School.

It took me a while to come back. Susan told me what was happening, but sure, what could I do? It’s not like I could unfrazzle his brain.

By the time I arrived at the nursing home, Terry had suffered seventeen strokes. I brought Mayan gold chocolates and a Get Well Soon Granddad! card—a musical fancy that chimed Louis Armstrong’s What a Wonderful World. Susan warned that he might not know me, but he seemed alright.

‘There you are!’ he boomed. ‘Donal, come in—excellent! I trust the cats haven’t been too noisy?’

‘What’s that, Granddad?’

‘The cats. They’ve not been causing a nuisance?’

He kept tigers. That’s what he said. Had four of them, out the back of the car park. Was minding them for the Maharajah, someone he’d worked with in the past. And then he winked, as though I should understand.

‘The Maharajah, right… Is he from the Central Statistics Office?’

A deep belly-laugh shook his frame. ‘Ah, that was a good cover—lasted me years! The Maharajah is moving palaces at the minute, and the elephants are his prime concern—fierce sensitive creatures. At least I’m not stuck with the white peacocks—can you imagine fifty of those feckers running around here!’

I replayed Susan’s words in my mind. She’d not mentioned Terry had gone stone-mad.

‘Gold’s a devilish sort of a thing,’ Terry declared, eyeing me. ‘Gold-greed rots the soul like a cancer. Not the Maharajah: that man treats gold with respect; uses it with wisdom; dispenses it with kindness. Thus has it ever been.’

I opened the chocolates and listened to his tales of the tigers. The kitchen porters of Castlegyleen Lodge Nursing & Residential Home sneaked out food for the cats. I was made lean out the window to the left, to Car Park B. Could I glimpse a striped tail between the Volvos and the hatchbacks? Only last week, one of the consultants discovered a scratch down the length of his Saab. The ex-wife was blamed, but Terry knew better. ‘Those cats have been through an ordeal to get here. Sure, they’re bound to act up some.’

When the nurse came in to change his drip, I peeked at the clipboard on the end of the bed. Not one of the medications was familiar to me.

Terry’s IV drip talks to him—did you know that? The thing is American. Broadcasts news reports about his food: ‘Good afternoon, this is CNN Special News. We’re going now live to Nutrition Inc., where Head Chef Bob Billywig will take us through the dish for the day. Bob…?’ Granddad hears background sounds: a busy kitchen, with things sizzling on hot grills. Then Bob Billywig speaks: ‘Well folks, Terry Bradley has a treat in store today! Elmer’s cooking up a quarter-pound sirloin burger with spicy fries, and there’s a slice of Martha’s key lime pie to follow—sheer heaven!’

‘It was blueberry pie yesterday,’ Granddad says, worry darkening his eyes. ‘I don’t know that I like key lime…’

The absurdity of it! That instant, my fears broke open and fell away from me. ‘You’ll love it, Granddad,’ I said. ‘Key lime pie is delicious.’

Terry looked at me, nodded. ‘You know that Bogart only played Sam Spade once?’ I relaxed back into the chair, taking a moment to trace the connection: key lime… Key Largo. ‘Just that once. The same with Philip Marlowe: played him one time and pow! The part was his forever. Once was all it took for Bogie. Indelible, that man was. Indelible.’

We chatted all afternoon, making our way through half the chocolates. Granddad might have been sitting up at the bar in Con. Easygoing, confident, affable. And I loved him this way—loved him—even if he was talking unadulterated shite.

The nurse finally came and ousted me. As I went to leave, Terry told me his Admission Form needed updating. He spoke four languages now: they should add Urdu, and Luxembourgian.

I grinned. ‘Isn’t this place fantastic?’

Granddad leaned back, his thin head sinking into the pillow. ‘They need to keep me safe. I’m important to them, to the Tribunal.’

That evening I stopped by Susan’s, where Granddad stayed until he was beyond her help. The caring had taken its toll: there was neither fondness nor pleasure in her voice. ‘Spent his days looking out to sea. Kept remarking how many dolphins were around. He thought every white horse was a dolphin; thought the sea was chock-full of them! I told him, but he wouldn’t hear it! Like that with everything, he was. Insisted the evening swallows were giant bats. Over from East Africa, he said. Wanted to point it out on a map! To me!’

On Wednesday, I brought yellow balloons and a copy of The African Queen. Thought I could read aloud, if Granddad didn’t feel like talking.

But he did: about how he worked with a secret government department; how his testimony would be crucial to the Tribunal. ‘Gold diggers and back stabbers, the lot of them! What gold does to a man’s soul, Donal, and he only falls the harder for it. A dangerous game…’ I suspected he was conflating the Tribunal with The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, but maybe not. I’ve been out of Ireland a long time. ‘Do you know, in all my years I’ve never heard the saxophone played live?’

I jumped over to the new conversation. Some Sundays, I brunched in Camden, at the Jazz Café.

‘Do you know that the man who invented the saxophone survived multiple assassination attempts? Even shootings,’ said Terry. ‘That man had enemies. His whole life, he was a victim of crooks and slanderers and jealous men. But that music…’ he shook his head slowly against the pillow. ‘Those notes. Haunting. Like starlight in a lonely place. And all those feathers…’

I stayed until he drifted off, mumbling the words that were coming from the IV drip, Bob Billywig describing the late-night snack that Elmer was fixing for Terry: a cup of Wisconsin Blue Ribbon chilli and golden sweet cornbread.

That night, Susan wept. She just wanted things back the way they were before.

Funny thing was, I almost felt they were.

When I opened his door on Thursday, Terry’s bony frame cowered under the covers. ‘Help me, Donal!’ he begged, tears streaming down his face. ‘For God’s sake, close the blinds!’

There was a sniper outside, waiting to take his shot. It was because of the Tribunal: Granddad had been tracked down. ‘I’m too big a threat,’ he said. ‘They sent me a warning, took out the white tiger with the blue eyes. Bang bang goodnight.’ The other cats remained in danger. Their food could no longer be trusted; the porters had been bribed.

I said I’d take care of the cats, but he turned on me. ‘And how will you feed three Bengal tigers? With your fancy investment accounts and your City of London. You’ve no local connections!’ Granddad turned his face from me. ‘What am I going to say to the Maharajah!’

I watched my grandfather weep.

Later, he was easier. He described his magical stay at Susan’s house: how the dolphins careered through the waves like a scene from a Grecian vase; how the bats swooshed through the twilight realm. Closing his eyes, he murmured. ‘I wish I’d heard the saxophone live. Wish I’d spoken to your mother before she died. Wish I’d sailed to Tangiers when I had the chance, traveled by caravan over to Casablanca. I could have gone to Luxembourg; to Lyme Regis. But the cards are dealt the other way now, dealt for the last time. There’ll be no more shuffling.’

I couldn’t tell what desires were real or imagined. What did it matter? I asked about the saxophone, the feathers. ‘Have you never seen, Donal? The notes transform into feathers, drifting across the air, soaring, swooping… And bullets can’t get through them, not saxophone feathers! The inventor saw to that. Survived multiple assassination attempts, he did.’

That evening, the IV drip came to life as Terry nodded off. It said men were coming for him. They would never let him testify, it promised. Soon he’d be sleeping the big sleep.

I watched him, remembering the pride welling as I walked into Cork Con beside that man. Terry’s boy, I was.

I started making calls on the way back to the hotel. It still took me a full day to organise everything. I practically hijacked Caroline and Soweto. We didn’t make it back from Dublin until after 11pm. The three of us sneaked in, with two rolling suitcases and the saxophone case. And the bin-bag stuffed with feathers.

Caroline went first. She explained that the Tribunal’s judge took a call last night—from the Maharajah. He explained Terry’s special circumstances. She would take his statement in Urdu—to keep it on the QT. She’d bring it straight to Dublin to be entered into evidence.

Granddad nodded, like he’d expected it all along. ‘That’s friendship for you! Half a world away, Donal, and it’s as if he’s in this room with me! We were no angels, back in the day. I got him out of a tight spot, helped him through a dark passage. And he’s not forgotten me!’

He started to speak, low and serious. Soweto put in his mute and warmed up. I unpacked: laid out the cake box; let out the goat and the rabbits—they were all I could get my hands on at short notice. I thought they’d reassure Granddad that the tigers would be cared for. I settled the animals as best I could, then blue-tacked up the pictures of Tangiers and Luxembourg and Lyme Regis.

The testimony brought Granddad some relief, I think. He checked over Caroline’s work, said she’d done a fine job. I witnessed his statement, along with Soweto here—on alto sax.

Then Soweto played. From the first sonorous note, Granddad was enthralled. I used four pillows’ worth of duck down, following the music rising and falling and whirling around the room. Long ostrich feathers did for the sliding glissandos and soaring crescendos. The whole time, Granddad stayed fixated on that golden swirl, big watery tears blurring his pale blue eyes.

I’m… I’m so sorry for all the inconvenience, especially the feathers, and the goat—I’d have been in and out if it weren’t for him. Caroline and Soweto came to understand my motives, but there was no winning over that feckin’ goat. The commotion started when he made a bolt for the cake box. The poor rabbits took fright, tripping up Caroline, who fell back on poor Soweto. Listen, I know I’ve a cheek to ask, but could someone see that Granddad gets to taste the key lime pie? It’s on his locker, a bit battered now…

I can go in myself? How’s that? You remember me from Con—a young lad sitting up beside his grandfather?

Ah go on. I’ve changed a bit, surely?

Orlaith O’Sullivan is an award-winning writer with a PhD in Renaissance literature. Her short story Gilt won joint first prize in the inaugural Fish-Knife Award (2006). Louisa and the Sea was short-listed for the 2007 William Trevor International Short Story Competition. Her short story A Tall Tale won The Stinging Fly prize 2008. She currently lives is Dublin, and is editing her first novel.

Read our interview with Orlaith here.

Beautiful, quirky, kind, eloquent, heart softening, wonderful images 🙂

Pingback: Interview with Orlaith O’Sullivan | Rkvry Quarterly Literary Journal