Brandi George: I’m always shocked by how much we have in common. We’re both from working-class families in the Midwest, and we’ve both endured childhood trauma. We are the first in our families to graduate from college, and we’re working poets and scholars. And yet, at least for me, this success often feels hollow. It’s tough to write through painful emotions while also teaching, researching, publishing, and competing for academic jobs (what a stressful sentence!). How do you juggle all of these different responsibilities while also writing powerful poems about your past experiences?

Jennifer Schomburg Kanke: I try to give myself the time and space I need for each thing when I need it. There was an old TV show on Lifetime back in the late 90s called Maggie and there’s a dream sequence scene where she’s learning how to spin plates and the secret to spinning plates turns out to be that you don’t have to have your hand on every plate at once. You keep your eye out and see which plate needs your attention and let the others do their thing. And I think that’s how I balance all my responsibilities, just keep my eye out for which plate needs me. Granted though, that’s tough when writing poems about the kind of life I’ve had because opening myself up to certain issues could make me unfit for human consumption for a day or so and you really don’t have that kind of luxury when you have 100 students relying on you. I have a good counselor and a lot of good self-care that lets it happen.

But another part of your question that I wanted to clarify is that I don’t always consider myself to be the first person in my family to have graduated from college (and some days I don’t consider myself to have had a traumatic childhood, but that’s another issue entirely). It all depends on how you define college and first, and even family. Only one of my grandparents was able to graduate from high school, but my father has an associates from a tech school and I always thought of that as “college” until I got to Ohio University and realized that most other people weren’t counting that. And my Aunt Bunky and my cousin Cindy finished their bachelor’s before I did, but they had both taken a lot of time off to have children after high school and came back as non-traditional students. So the joke in the family is that I’m the first non-non-traditional graduate. But according to all the Federal programs for first generation students, I’m a first generation college student because, by their definition, my aunt and cousin aren’t “family,” family is only immediate family to them. And I’m not sure if that definition of family sits well with me. My family is rooted in Appalachian traditions and family is incredibly important to me.

BG: Writing about family members can lead to hurt feelings, conflicts, and often, guilt. We don’t want to hurt the people we love, and yet they have hurt us. How do you hold people responsible for what they have done, while also taking into account their own, often traumatic, lives? What role does poetry play in this process?

JSK: I don’t know if I’m particularly interested in holding people responsible for what they’ve done. It might sound self-centered, but my goal is my own healing and placing responsibility or demanding atonement isn’t a large part of that. Not to bring up TV again, but there’s an episode of Northern Exposure where authorities from West Virginia come looking for Chris and they try him for something he did a long time ago. He’s able to get off by proving that he’s just not that same person anymore and so can’t be tried for the crimes. I can’t try my family for crimes their old selves committed against me. Well, I mean, I can, but I’m not sure what good it does any of us. It doesn’t change the past. It doesn’t change how those things have affected me or how they’ve become part of my own self-perception and self-talk that I have to fight against every day.

What I am interested in being able to do is to have conversations with them about what things were like back then and how those things effect the person I am today and the life I’ve had since then. And that’s where poetry comes in for me. It opens up those conversations in a smoother way than me trying to just brazenly bring it up. Which probably says a lot about my personality that I think it’s easier to write a poem, publish it where anyone with an internet connection can see it than to just say “hey ya’ll, that sucked, let’s talk about it.” Maxine Kumin once said that writing in form helped her deal with tough emotions because it gave her control (or something of that nature) and I think poetry in general also does that for me.

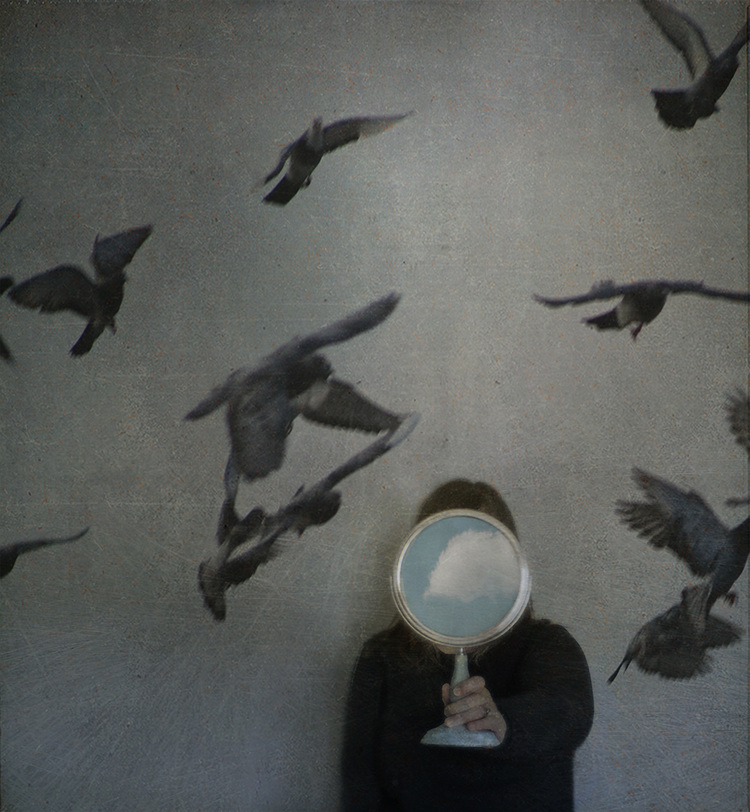

BG: Personally, I’ve found that there is great power in the images that are pulled from traumatic experiences. In your poem, “I Am Not Worth $8.50,” you open with the following image:

The hallway mirror is veined with gold paint,

each square a repetition of the last,

making the distance from the living room

to my bedroom look farther than it is. (1-4)

The image is resonant and unsettling. Would you talk a little about how and why you chose it? Do images do a different sort of work in poems about violence?

JSK: Is it a horrible and unpoetic answer to say that I chose it because it’s just what the end of the hallway looked like? I know, I know, that’s a simplification and there are always layers to any choice that we make. We lived in a three bedroom ranch and the hallway with the bedrooms and bathroom were off the living room area. I spent a good amount of time running from that living room, trying to make it back to my bedroom and get the door shut. That mirror (a sort of ghastly relic from the previous owners) is burned into most of my memories, it was always like I was running toward myself. Safety was my own image. Or at least my own image adjacent.

I don’t really think that images do any different work in poems about violence than they do in poems on other topics. The image’s job is always to give us access to the moment, whether that moment is one of violence or of ice cream and unicorns, or of violent unicorns eating ice cream. The image is like that episode on Charmed when Prue and Piper get sucked into the painting. The image is the magic spell, there to pull us in and not let us go. Or at least part of that spell, the other part being the use of rhythm and sound elements. It can be easy to overthink it all and what those lines are between the image itself and the way the image is rendered, especially when writing violence.

BG: It’s easy to overwrite painful experiences, but “I Am Not Worth $8.50” does a lot of work in a very short space. How did you arrive at the final draft of the poem?

JSK: Would you hate me if I said the poem really only had one draft? There were a few tweaks, mainly with me trying to decide how much a lock cost in the mid-80s and deciding how forthcoming to be about how long it took for the lock to break. In my poems where I’m trying to be honest about what my life was like and how I felt about it, I have to go for shorter because if I let myself think too long or write too long, I start making jokes and referencing pop culture stuff. Which is cool, I love pop culture, especially TV (as I’m sure is probably pretty apparent by my earlier answers), but I use it as a protective mechanism. Which works wonderfully in my fiction ( I think, I don’t know, I guess you’d have to ask editors who are looking at my submissions to get a real answer on that one!), but for poetry I think it doesn’t work as well. It becomes a shield against the pain. And there are days when I really want that, but if I want my poems to do the work I’d like them to, I’ve got to put the shield down and come just with my heart open. My crazy, needy, angsty little heart.

BG: You are one of those lucky, multiple-genre writers. Are there other things you can express in your poetry that you can’t express in your fiction and vice versa?

JSK: I think poetry lets me express things faster. Poetry lets me do a ripple effect thing, it takes five seconds for the pebble to hit, but you’re seeing the disruption on the water for a few minutes after and it’s spreading out over the whole lake. Fiction lets me hide more. And I’m a big fan of hiding. I feel like poetry gives me less wiggle room with the facts. I try to stay as close to the truth as I can with poetry. I know that’s not the way it is for everyone, but it’s the way it is for me unless I’m being very clear that it’s a persona poem. I still honor the lyrical I. I think poetry comes from a sacred place and you defile it by taking too many liberties with the facts of the situation. Those liberties become ways of hiding from the truth and from ourselves. That said, I think a little bit of tweaking (like saying something’s blue when it was really red if that scans better or emphasizes a point or saying it took a month for a lock to break when really it was a much shorter period of time), is okay, but not much more than that. But with fiction I can mix my real memories with other things that are completely made up and no one knows which are which. That makes me feel safe and comfortable and hidden. I’ve been trying to write creative nonfiction and that’s not going so well. I don’t have the “Truth instead of truth” of fiction or the vagueness of poetry to hide behind. I feel a little too exposed in creative nonfiction. I’m also just more familiar with the forms of poetry than with creative nonfiction, so there’s that too.

BG: “I Am Not Worth $8.50” is not written in a traditional form, and yet it has a very strong sense of sound and rhythm, including a few iambic lines. What is your relationship to traditional forms, and what role do they play in your work?

JSK: When I was a kid I was a voracious reader and my wonderful Aunt Jannie, one of my father’s sisters, would take me to the Goodwill Bookstore, which she called “The Day Old Bookstore” (because we’d also usually hit up the day-old-bread store while we were out). There wasn’t a lot of selection for a tween, but there certainly was quantity! For fifty cents you could get a paper grocery bag full of books, but you had no idea what was in the bag before you bought it. I got lots and lots of Nortons and old poetry books that way. So, Thomas Campion was my first poetry love. Not Shakespeare, not even Spenser, nope, Campion all the way. And Campion was also a composer who did music for masque dances and songs for lutes. My parents also loved Steeleye Span, a British folk rock group, and we were in a contra dance band together. The early forms I was exposed to were all musical forms. I don’t think consciously about sound and rhythm too much, I just feel it, I dance it. Of course, I’m also a child of the 80s and 90s, so sometimes that dance is slam and sometimes it’s the pogo and sometimes it’s the Boot Scoot Boogie. But I also love sonnets, but that love came later when I took English classes in college and then studied poetry more deeply in graduate school.

BG: Since you began writing about your childhood, you’ve received messages of gratitude from readers who have endured similar experiences. What poets do you feel thankful for?

JSK: That’s a tough question. I think the answer to that has changed over time I’m grateful to Gwendolyn Brooks because she showed you could take a formal foundation and build something new and powerfully contemporary out of it and also for her poem “a song in the front yard,” which, along with Wordsworth’s “The World Is Too Much with Us,” is one of those poems that just pops into my head when I’m in a bit of a mood. I hear them in my mind and think, “yep, other people were sick of this shit too” and it makes it easier to put one foot in front of another. Catie Rosemurgy’s “The Office Party” is another one of those poems. Her line “I want my maybe back” is pretty much the story of my life and I love her for that line. I feel grateful to Anne Sexton and Marge Piercy because they were the first female poets I read that talked about things I didn’t realize you were allowed to talk about in poetry (because, remember, I’d been reading Campion and Donne, and other members of the Old Bros’ Club).

I’m also thankful for Marge Piercy beyond her work though because she was the first person to tell me that my story needed to be told and that I needed to stop hiding behind poetic craft and just say what things had been like. She, and the other poets that were in her annual workshop in Wellfleet this summer, made me feel that my voice was important and that my story and the story of my family is just as important as others. Because I tend to downplay it. I never became a drug addict or had affairs or did anything all that exciting by the standards of contemporary poetry (I’ve played only in the front yard, in Brooks’s terms). I had a 3.9 GPA in high school and undergrad and went on to get a PhD. I’m the kind of person who people are surprised has had the kind of life I’ve had, probably because I’ve learned to just not talk about it. Marge made me see that that resilience is exactly why I need to be writing about it, to show the variety of experience.

I’m also thankful for Mark Halliday, J. Allyn Rosser, Janis Butler Holm, Barbara Hamby, and David Kirby for not only their great poems, but also for putting up with me in graduate school while I’ve floundered around trying to find my voice. And Josephine Yu,Wendy McVicker, Becca Lachman, Kathryn Nuernberger, Lydia McDermott, and you for being great writing and personal supports as I work on this stuff. The orchestra’s probably about ready to play me off on this question, but believe me, I could go on and on with this. There are so many poets who have made a difference to me with their work and also with their love, support and community. You write poems alone, but you need community to be a poet.

Brandi George grew up in rural Michigan. Her first book, Gog (Black Lawrence Press, 2015), won the gold medal in the Florida Book Awards. Her poems have appeared in such journals as Gulf Coast, Prairie Schooner, Ninth Letter, Columbia Poetry Review, and The Iowa Review. She has been awarded residencies at Hambidge Center for the Arts and the Hill House Institute for Sustainable Living, Art & Natural Design, and she attended the Sewanee Writer’s Conference as a Tennessee Williams Scholar. She currently resides in Hattiesburg, where she is Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Southern Mississippi.