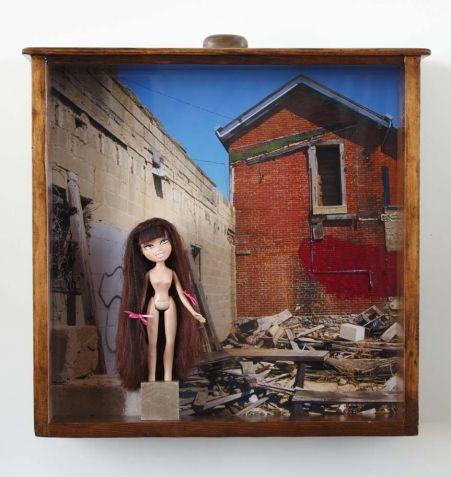

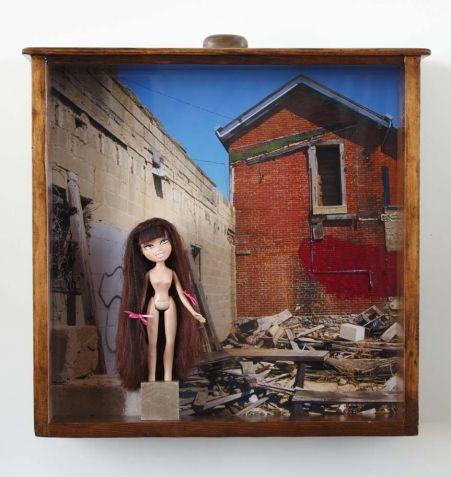

Jade-Bratz from the TOYOLOGY series, by Elizabeth Leader, 2011, Mixed Media Assemblage

Continued from Part I

The freckled boy locked the door behind them. He was sweating. “It’s amazing you’re even alive,” he said. “We saw a whole cow fly by. A whole entire cow.”

“This is my husband,” she said to the fat boy. To her husband, she said, “This is the boy that put Coke in my iced tea.”

They shook hands.

“It wasn’t dead,” the boy said. “Its hooves were stomping the air.” He demonstrated with his puffy fists.

“Thanks for that, Skippy,” she said.

Dmitry made a beeline for Kenny, throwing his arms around him. Tera supposed that it was odd of her to call Kenny for help, but she had known he would come. Men want to rescue you. And sometimes you want to be rescued.

“The phone lines are down or I would have called you,” Kenny said after they’d settled in a booth. He gave a nod in the direction of his quivering vehicle. “I’d have told you to stay at the facility. The reports say this one is a monster.” He nodded his head in a different direction. “Julio has a radio. We got an update before the batteries gave out.”

“Tornadoes are mercurial storms,” Dmitry said. “They may destroy a single house in a neighborhood and leave all the others untouched.”

“There’s a bottle of whiskey in my car,” Tera said. “Do you suppose Skippy would be willing to fetch it?”

“We’ve missed you,” Kenny said to Dmitry. “The whole department. Students ask about you daily.”

“Students,” Dmitry replied. “There’re so many of them. Aren’t there? Generation after generation of students. We should probably all gather in the bathroom, don’t you think?”

Kenny sent her an S.O.S. but she was making sense of hubby by this time.

“The safest place in a storm,” she said, “is the bathroom.”

“Of course,” Kenny said, relieved. “Why is that I wonder?”

“Small size,” Dmitry said, “wall strength, the fixtures.” After a moment, he added, “Interiority.”

It was then that the immense funnel showed itself in the windows of the Hardee’s, a great undulate of white rope. Some bored god with a lariat the size of the Sears Tower.

—

Skippy and his gang claimed the Guys, which left them with the Gals. A small, translucent window covered with chicken wire let in smeared dollops of light. Dmitry sat on a toilet in the handicapped stall, and Tera sat on his lap. Kenny was in the adjacent stall. If she ducked her head low, she could see his sneakers. The bathroom tile and metal stalls turned their voices hard and made them bounce like rubber balls about the room.

Her men talked for a while about changes in the department, how one of Dmitry’s enemies had made a push to usurp the planned hire. The sociology department was divided along theoretical lines, much like Europe in the first half of the twentieth century, and battles periodically erupted. Dmitry and Kenny tossed volleys back and forth over the metal wall about internecine hostilities. Tera had studied in the department for three years, but she was content to listen, recalling the afternoon in his office that she told him she was quitting the program, and how he took her into his arms (they were lovers by this time) and she curled into his lap, smelling the leather of his chair. The toilet wasn’t quite so comfy, but she felt finally at ease. He sounded so much more himself talking about an assistant professor who did arbitrary interviews with the poor and published them as research, validity and reliability be damned, and how another colleague, who collected and analyzed monkey sperm, hated the assistant professor so much that he hired undergraduates to answer her ad and pose as the homeless. Universities were home to the most extreme kinds of idiocy.

Dmitry said to Kenny, “I’m aware, of course, that you and my wife had intercourse.”

She kept her head bent against his chest. The other stall fell silent. They could hear things outside bumping against the shabby building. Girders squealed, as the wind tried to rip the lid from the box.

“Sexual intercourse,” Dmitry clarified.

“I understand you,” Kenny said. “What do you want me to say?”

The next silence was even longer, but the world happily stepped into the gap, and it occurred to Tera to say that the wind was the sky’s way of complaining. She had confessed to Dmitry some weeks ago, during one of her visits to the farm. He hadn’t responded, and she hadn’t been sure that he was tracking the conversation.

Finally, she said, “I’m sorry.”

“Yes,” Dmitry said. “You told me that.”

“Something’s happening underneath,” Kenny said. “The water’s rocking.”

“Don’t you lose your mind, too,” she said, an inconsiderate remark, considering.

“The water in the toilet is full of waves,” Kenny insisted.

They stood, lifted the lid, and looked.

“It seems to be rising,” she said.

“It’s attempting to communicate,” Dmitry said. “It’s weary of its life. We only think of the sewer when we have something foul we wish for it to take away.” He leaned lower. “Forgive us,” he spoke this directly into the open mouth of the toilet.

Strange spears of light entered the stall, and Kenny stepped in, joining them, latching the door behind him. He pointed upward, but stared at them. “We should hold each other,” he said.

The ceiling was rattling, and a peculiar, strained light leapt in the gaps. Wires, electrical coils as thick as Tera’s arms, held the hovering ceiling, kept it from continuing its levitation. Everywhere beneath them, chained to them like the famous cannon ball, was the betrayal, in which Tera and Kenny did terrible and wonderful things behind Dmitry’s back while he continued to do nice things for them.

And that second betrayal, when she refused to continue loving Kenny despite Dmitry having removed himself from the picture; that was there, too, in the darkness beneath their forked bodies.

“It may be a septic system out here,” Dmitry said, clutching her tightly. “Not a sewer system, per se.” His face was lit by an unholy flash of light, as if by divine touch, and then it went dark. Her men crowded around her, holding her tight.

The howling was suddenly fierce, and Tera yelled out that she loved him, without saying which him, and held tight to them both.

—

Skippy was unconscious, and the place was a certifiable mess. Much of what had been the top of the building was now in the parking lot and on the highway, and rain fell through the gaps. All the loose furniture—the freestanding chairs and tables, the newspaper rack, and the March of Dimes candy dispenser—were gone, erased, still whirling over the Midwest somewhere beyond their ability to see. The booths were missing their tables. The seats and backs had inflated with water, and damp stuffing burst from the seams like sea creatures emerging from primordial caves. A great blossom of grime was laid over every item that remained in the room. There was no litter on the floor, only puddles, streams, tributaries, and poor fat Skippy, lying on his back, Dmitry and Julio kneeling over him, while Kenny and a spare Hardee Boy used mops and towels (the storage room was undamaged) to keep the growing flood away from his great, beached body. Tera’s cell phone no longer worked and the landline didn’t even offer static.

The men pumped furiously on Skippy’s chest, as if he were deflating. During the height of the storm, he had inexplicably left the Men’s and darted out into the chaos.

“He didn’t say nothing,” Julio offered, apologetically. “It was no way we could go after him.”

After a long while, they gave up their efforts.

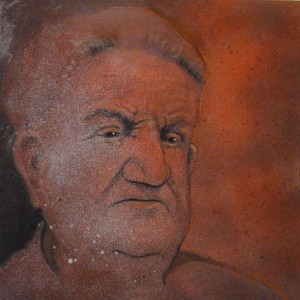

Tera had expected death to lend them a sense of wonder, to provide a spectacle, or at least a profound moment or two, but he merely looked cheapened, like a toy the day after Christmas.

“He’s peed himself,” Julio said, backing away.

The storm had been kind enough to bring Tera her car and nudge it up against the flagpole. Unfortunately, it was parked upside down. The passenger door was gone, but the glove box was intact and shut, and when she popped it open, the fifth of whiskey plopped into her waiting palm.

Dmitry took too many swigs of it. The liquor emitted a mixed set of signals to his brain, some of them sane but unkind (he punched Kenny in the chest) and some of them insane but helpful (when the rain abated, he filled his shoes with grease from the kitchen spill and built a fire in the parking lot, where they roasted frozen meat patties). His conversation rambled from sharp-edged replies to meaningless, idiosyncratic comments. When his mind had been clear, his intellectual passion was a fearsome thing to behold, a deep well of icy water, frigid to the skin and almost too cold to drink, but as clear as snowmelt and as quick as death.

At some point, Julio took each of them out to the road to see: the tabletops from the booths were laid out on the highway in a row, like the keys to a piano.

It was the smell of flaming meat, they would later speculate, that brought Skippy back from the dead.

“God, that smells good,” he said, stumbling out of the ruined Hardee’s and into the parking lot, sopping wet and walking funny but undeniably alive. The fire provided the only light, and in that grease-fed blaze, he looked pale and otherworldly, and Tera knew she wasn’t the only one who thought he had taken a journey and returned.

“Jesus shit,” Julio said. “You all right?”

“My chest hurts is all.”

“We thought you were dead,” Tera told him. “Dead dead. Not like, dead for a while.”

“Holy cow,” he said. “Dead.” He made an awful face. “You just left my body in there?”

She shrugged. “We were sort of hungry.”

“Kinda sucks that nobody even, you know, sat with the body.”

“We’ll do better next time.” She crossed her heart.

Stars emerged, pricking the dark, but there were too many of them. “The constellations are gone,” Dmitry said, pointing. “They’ve been cut loose. They’re all on their own.”

“What’s it like to be dead?” Tera asked.

Skippy shrugged. “I didn’t feel any difference.”

“Why you run out into that shit?” Julio demanded.

Skippy pondered that for awhile. “Something I’d forgotten,” he said and then snapped his fingers. “My umbrella. It was under the counter, and I thought I ought to get it.” He smiled and shook his head in something like wonder. “All other thoughts left my brain, and I just ran out after it.” He looked up at the nameless stars for several seconds. “It has a silver tip,” he clarified. “That umbrella does.”

Tera was young enough and she had extended her education long enough that she could still say that she had been a student for most of her life. Unless she went back to school, though, that would change, and how would she think of herself then? Sometimes she seemed like a sheet of music on which someone had typed prose, and so, on fresh blank paper, she worked to create a narrative, but what came out was a set of lyrics. It seemed likely that her tombstone would be covered with finger-paint.

In the days to come, she would find that her husband was both eager and apprehensive to return to his old life, where he was exceptional and treated with deference, where the possibility of being undone by a foolish girl he had taken into his home was as unlikely as the presence of thieves who break into your house to leave gifts. Eventually, he would become himself again, the revered professor of sociology, loved by students and admired by his peers. Except he would no longer care for research. He would give up his great theories, the beautiful speculations on the causes of heartache and suffering among the masses. He would quit opening the journals that arrived in the mail, never ripping off their transparent covers. He would even give up the newspaper. He’d had such a specific and specialized view of the world, and yet he ditched it without so much as a whimper. Tera could only imagine the outlook he had abandoned, where events of the world conformed to reasonable inquiry. While most saw chaos and irrational grief, he had seen reasons, a hidden order, and irrational grief.

One night, years after the storm, Tera and Dmitry would go to a revolving restaurant in a high rise, and beyond the window radiant droplets streamed in unison on the distant freeway, and she realized this was how she thought of his research, the view it gave him, things boiled down to their essences and moving in a pattern. He had this view while the rest of them had to walk the streets. It seemed like a lot to abandon.

“It wasn’t dark,” Skippy said suddenly. “Being dead. It was real colorful, like magazine pictures tossed ever which way. And I wasn’t fat, so much. But it was real loud. Lots of voices saying things in two million languages, and there was construction going on. I knew if I hung around I’d have to pitch in.”

“So you came back alive instead,” Julio said. “Being a lazy bastard finally paid off.”

Skippy had this way of shrugging that made his neck disappear. “It was more like there was a spring, a coiled metal spring, with like a steering wheel on the end of it—is my car out here at all?” He glanced about for only a second. “I clung to that steering wheel, and the spring was, you know, thrusting me out, but I didn’t let go and it sprung back, and that’s when I smelled burgers and opened my eyes.”

The night air had been softened by the parade of large objects flying through it, and a mist settled about their faces and skin and clothing, and an owl started in with a lonesome hoot that was almost mechanical in its alteration of pitch.

“That must be the cops,” Julio said.

“That’s a siren?” Tera asked.

Dmitry said, “I thought it was an owl.” He laughed at himself.

She didn’t tell him that she had made the same ridiculous mistake, but it pleased her that they shared that error and made her optimistic that they might make a go of it after all. There appeared then little moons of lights, to go with the siren, twin moons, as if they really were on a foreign world. And then twirling blue beacons took over the sky.

Kenny would finish his PhD that May and go on the market. Dmitry would write an enthusiastic letter of recommendation, and Kenny would take a job out West. They would hear about his marriage to a blandly attractive woman and the fact of their children, but he did not send cards or email photographs. He and Dmitry would occasionally run into each other at professional conferences, but Tera has not seen Kenny and has not heard from him in all these years, and while she had worried that she might be tempted to cheat on her marriage again, it never happened. She can say for sure that it will never happen, as her husband lies in the next room dying, and she works on these pages between visits. This is a new hospital, and she can see the river from the waiting room, a curling blackness that winds through the city. But it’s not Dmitry’s dying that she wishes to write about, and not the past several years, which have been like any couple’s years—a song with a good chorus but mixed verses. They never had children and that is both a relief and a regret, and Dmitry never wrote another professional word, which is unquestionably Tera’s fault but she has made her peace with it. She doesn’t care to write about any of these things, just that night, all those years ago.

The woman’s nose has been reconstructed to look like a pennywhistle, her ears unnaturally flat against her head, like cloth flaps. She no longer looks like a koala. She looks like gecko. Tera goes online to find a phone number for the Hardee’s, which she has passed maybe fifty times since that night without ever making a return visit, a brand new and equally hideous building having replaced the old one. No one at the new Hardee’s was employed fifteen years ago, but the manager is interested in her quest and willing to go through the employment files. “That storm,” he says while perusing the records, “I was in college at the time, but my mother witnessed the funnel. As tall as skyscraper, she said.”

Julio’s number belongs to his parents, who reveal to Tera that he has moved to Los Angeles. They provide the number.

“There wasn’t no Skippy,” Julio says.

“The freckled boy,” she explains. “Overweight? He died and came back to life?”

“Oh, him,” Julio says. “He died again a couple weeks later. Went in his sleep.” He sighs and adds, “That’s how I want to go.”

Dmitry will almost certainly go in his sleep. He rarely opens his eyes. Yet she believes he can hear her, and she recognizes his attempts to respond, though they are the smallest of diminished movements. She will try to be beside Dmitry when he dies.

“Poor Skippy,” she says.

“It wasn’t Skippy,” Julio says. “It was like Larry or Lance or something.”

“Lazarus?”

“You got a bad memory on you.”

She wants to know why he died.

“The doctors said internal injuries. That was some storm, all right. What I remember most is the tabletops on the highway, just like stair steps, only not going up.”

She thanks Julio and says goodbye. In another moment, after she has composed herself, she’ll go in and read to her husband what she has written, but she is not quite finished writing.

Out there in the Hardee’s parking lot, she had felt drowsy and sluggish, as if she had been living another person’s life. The dark was returning everything to its proper shape, erasing the magic, the stars settling again in their familiar patterns—though there were more stars than she had ever seen. Even the shyest of the celestial eyes had stepped forward to look.

Without any of the human forms of illumination, save for the fire, the bandage of night was complete, and Tera and her men stopped bleeding. They stood near the heat with their hands to the flames in the gesture of stop, as if they wished to hold back, to limit the influence of light a little while longer. She imagined them as the first humans, walking upright but communicating by crude gestures and guttural noises. The margins between the past and present had been blown away, and they huddled together as several forms of themselves. Tera was at least a dozen women standing before the fire, and some versions of Dmitry loved her and some hated her, and some had not noticed that she was there. And the Kennys and Julios and Skippys and those other working stiffs all gathered at the flames, a bundle of humanity. They had become a crowd, a crown, a vast recollection of life, which was what Dmitry studied, what he had used that precious mind of his to investigate and analyze. Bodies of people.

Her epiphany in the Hardee’s parking lot, a half-dreamt vision. Write about that night, she would say to Dmitry in the years to come. He would just smile and rock his head to one side, content in his textual silence. You write about it, he would say.

“What I’d like to do next,” Skippy told her, “now that I’ve been dead and all…” He paused to bite the burger in his hand. They had no buns, and his patty was hot. Grease on his jowls glistened in the firelight. “What I’d like to do next…”

But the sirens grew suddenly louder and the gaudy light show ended the adventure. They were packed off into cars, and Tera fell asleep in the back of a police cruiser, nestled between Kenny and Dmitry, the bodies of people she loved.

Robert Boswell has a new novel, Tumbledown, from Graywolf Press. He has published three story collections, seven novels, and two books of nonfiction. More than 70 stories and essays have appeared in the New Yorker, Best American Short Stories, O. Henry Prize Stories, Pushcart Prize Stories, Esquire, Colorado Review, Epoch, Ploughshares, and more. He shares the Cullen Endowed Chair in Creative Writing with his wife, Antonya Nelson. They live in Houston, Texas; Las Cruces, New Mexico; and Telluride, Colorado. They also spend time in a ghost town high in the Rockies.

Read our interview with Robert here.