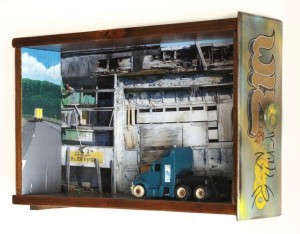

“We Repair Trucks,” by Elizabeth Leader, from the Toyology Series, Mixed media assemblage

Netta dipped inside the case with her metal scooper, fearing she’d perspire right into the barrel of chocolate chip mint. She wiped at the drop of sweat making its way down her nose with the back of her hand. What with the humming and heating of the freezers, she was already dizzy red hot in early June. Only thing cool about her was that one strip of belly that leaned right up against the freezer when she bent in to scoop. It was the coolness right there, where so much hurt and wanting had seared into a congealed mass of love, that made her remember the old truck sitting idle out back.

“You got to get that truck fixed,” she said to Rex, looking so fresh with his hot coffee of all things on such a day. That steam coming up over the rim of his cup just about made Netta swoon. “How you sitting so cool over there, Rex, honey? I’m burning up to hell here.”

“It’s too early for summer fever,” Rex said to her. Netta looked out through the Waratah Homemade Ice Cream sign etched onto the glass of the big plate window. Sky outside was nothing but a suffocating haze of Lake Michigan air, wet and heavy, waiting on something to break.

“You come on over to my side of the counter and try scooping with these condensers heating me up so.”

“I’m reading the want ads, Netta-bird.”

“What you ought to be reading, Rex, honey, is the how-to on getting that truck out there up and running. It’s time.” She turned to the boy, the youngest of the Van Dwek kids, waiting on his cone. “It was the Waratah fortune, that truck was,” she said. “Ain’t that so, Rex? Your granddaddy brought it home spanking new, shining white with blue trim. I saw some pictures. Boy, that was a proud day, wasn’t it, Rex? You want sprinkles, honey?”

“Never was much of a Waratah fortune. My papa should have sold it for scrap.”

“I remember the truck at Pink Lake last summer,” the Van Dwek boy said.

Netta caught Rex glancing up at the boy. He had his palm resting on the paper, a finger extended on the page as if it were the only thing keeping him upright. “You go on down to Mitchell’s garage,” she said to Rex, “see about that refurbished engine we talked about and those spare parts. See if they come in yet. What else you got to do today?”

Smiling at the boy, she said, “Why, you look so like your daddy.”

“There’s a rain coming, Netta-bird. Let me wait it out in peace,” Rex said.

The boy dug into his pockets for loose change. Netta waited. “Skies like blue hope, now, ain’t that what follows a summer rainstorm? Nothing more hopeful than that. Blue skies after a storm. You go, Rex, right after this weather blows through, you’ll get on that truck, go over to Mitchell’s? Get that truck working again.” She winked at the boy. “Maybe put in some working air-conditioning? Now won’t that be something nice.”

“I got a quarter and ten dimes,” the boy said, looking at the change in his hand.

“You sure you don’t have another quarter?”

“Last summer you let me have it for whatever I had in my pocket!”

“Now that doesn’t sound like me. Does that, Rex? Giving away ice cream at bargain basement prices.”

“I was with my brother William, and it was the last time you came out to the lake with that truck, the one you was just talking about. I remember because you dropped William’s cone.”

Netta could see the vein at the corner of Rex’ forehead, on the left side just above his eye, pumping blood fast like he was trying to heat up something that had just about froze over.

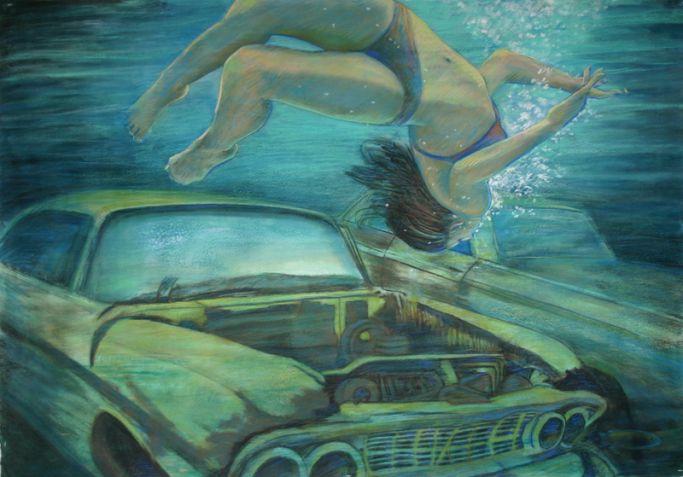

“It was near on to ninety that day. Rex remembers. I was sitting on a whole lot of heat. Stepping out of that truck on to the swelter of asphalt did nothing to cool me. Rex had gone off for water—that damn radiator couldn’t hold more than a one way out to the lake—and I was working the truck.”

“And you scooped William out another and said you can scoop quicker than the one on the ground would melt. That’s what you said to me and William, and you took what I had in my pocket for the $1.50 sized cone. And nothing for William’s second.”

Netta had been half in half out of the side door on that truck pulling on the strawberry ice cream when she felt a sigh from deep within her. She dropped the cone and touched the widening side of her belly where her hand measured the seven months of baby.

The Van Dwek boy was holding out all he had to give to Netta, still short a quarter.

“Now, does your papa give his blueberries and peaches away, and your momma her pies, for a smile, now do they?”

“She’s not baking on account of the new baby. When my middle brother was born, we didn’t have one of her pies until his first birthday. That’s why I came down here. You can’t take a baby to a hot beach, that’s what Delia said when I was looking for your truck yesterday at the lake.”

Rex stood up, cracking his chair against the wall, giving flight to those circled want ads. When Rex had returned to the truck that day with water to quench the radiator, they started toward home. Netta told him to take the Gas Junction Exit and head on straight to the hospital. More than anything she was surprised at the work it took to birth that dead baby, just as much as she imagined it would be one that was kicking and screaming and looking for her breast.

Netta gave the boy his cone. “I’ll take your $1.25 for a $1.50 cone today, young Mr. Van Dwek. You tell your momma and that new baby hey from me, okay? Maybe I’ll make you all a pie and bring it over for church picnic some Sunday. Your family still goes every Sunday, ain’t that so?”

“I knew you’d remember!”

“Now get on going home before the rain starts.” Netta watched Rex watching the boy. The boy opened the door just as a shot of wind came thrusting through. “Here it comes!” the boy shouted as he went running into the beginning rain, the wind slamming at the door. Another gust came just then, and the door got so caught up by that wind it flew back open. The bells on the window over top jangled and the screen rattled. The wind whipped back, doubling in with a blackening sky. Rex jumped to grab the door, but Netta had come alongside him and stood in the opening. Her skirt and apron caught the coiling air and flapped into twists around her legs. Her hair had come loose. She inhaled and felt cool even before she stepped out into the rain.

“I’m not ready for church, Netta,” Rex said.

“You didn’t hear me make any promises, now did you, Rex?”

A shuddering of thunder sounded, and a flash of lightning followed far off in the distance.

“I should have fixed that truck last year, when it was just the radiator. Would have been nothing. Now, it’s the whole damn engine,” Rex said.

“Nothing that can’t be fixed, or replaced.”

“Them doctors didn’t sound too hopeful.” It was at the hospital the truck wheezed its last, and the engine cracked right there in the parking lot. They had to hitch it up and tow it back to the ice cream shop. Took what little money they had saved for a crib and stroller, some cotton tees and diapers, and used it instead for a solid birch box. Netta’s people came, walked with her through the black iron gates of the cemetery so she’d have someone to lean on in the late summer heat when the little box, that little box, was lowered deep into the ground.

“Look out there, Rex, you can see blue sky coming right in behind the storm, just like I said.”

“I wish I could feel it, Netta-bird, I wish I could feel that blue sky coming.”

Netta took Rex’s hand and placed it just south of her belly. His hand stretched out over the flatness of her belly, but just in the center where she had placed his palm, ever so slight, there was a quickening that made her heart race the wind.

“You telling me something, Netta-bird?”

“You’ve got to get that truck up and running. That’s all I’ve been saying. What’re we gonna do, Rex? Let it sit and rot?” They stood in the rain, his hand on her belly, waiting on that blue sky. Netta never took her face from out of the wind. She swayed on her feet, humming with her body, and felt Rex stirring with the heat of something lost between them.

Erica Jamieson writes fiction and creative non-fiction. Her work has appeared in print and online at various journals including Lilith, Spittoon and Self Magazine. She lives in Los Angeles with her family and mentors at risk teen girls through creative writing with the non-profit WriteGirl. She can be reached at ericawjamieson.com

Read an interview with Erica here.