Maiden Estep leads the Red Hat into Number Six at Bear Town, where the mine starts. They walk at first, back to the crawl, miles deep inside, under the town of Grundy. Already, they have cut a strip in both directions, and soon they’ll be coming back through the middle, robbing pillars it’s called, the most danger any of them have been exposed to except the old guys, the robbing line and the dynamite guys. Maiden runs the scoop, loading what they dig and blast loose onto the conveyor that carries it out through the mountain and into the yard. A couple times a night, he climbs off the scoop and crawls along the belt throwing pieces back on that have fallen over, up and down the narrow gangway.

The Red Hat’s name is Charlie Hawkins, barely out of high school. Most of the men know him already. Got a little girl pregnant his junior year. Who hadn’t gotten a little girl pregnant at some point?

The kid’s tall, six-five or six, there abouts, and carries it all through the legs, not the trunk of his body as some men do. From the knee to his hip, he is nearly as tall as the mine is deep in this section, so the crawl behind Maiden is cumbersome.

“Don’t bow your back,” Maiden warns. “4160 running overhead.”

Maiden is only a White Hat himself. This is the first time he’s been part of robbing pillars, and he is uneasy, even though the actual pillar robbing is not his job. Once they’ve humped out the vein they’re working on, the robbers will come behind and start pulling the pillars, the mountain collapsing at their heels.

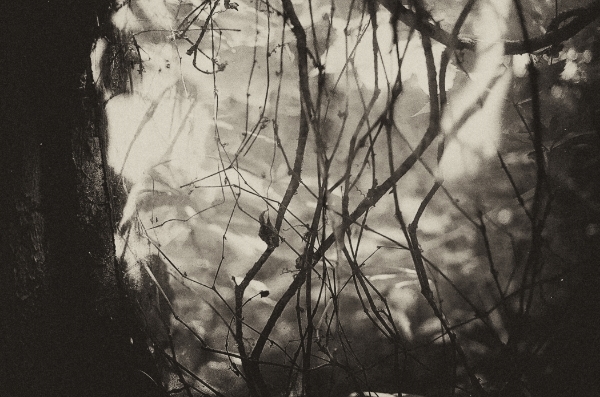

There is water standing in ruts along the crawl, which dampens the knees of their work pants. Occasionally they hear a drip, but once they travel deeper inside, the floor of the shaft becomes dry again. Visibility is only possible by the dim lights of their miners’ caps, powered by wet-cell batteries. Overhead, the 4160 hums in Maiden’s ears.

The only other thing so far that has spooked him is the blasting. When the dynamite men come in, the others hunker down where they are and protect themselves as best they can. The only real thing between them and fire-in-the-hole is prayer. Not even the unbelievers chance it. “Faith can move mountains,” the miners say. “Just pray like hell it don’t have to.”

A case of the nerves makes the Red Hat natter on about something or other behind Maiden. Baseball. Goose Gossage. Maiden has never watched a game of professional baseball or any other sport, on television or anywhere else, but he can’t imagine pulling for a player from New York City. He likes only westerns and war movies, though he doesn’t mention it to the Red Hat. Maiden lets him blather on, respectfully saying nothing, only occasionally issuing a calm reminder now and again about the current running overhead.

The Red Hat is having trouble, though, and somewhere deep in the pit of Maiden’s stomach he knows something’s going to happen. Something bad. It’s as if a ghost has suddenly whispered in his ear. His flesh crawls all over and he throws another piece of slab up onto the conveyor. Then he turns to look at the Red Hat, low-crawling for every penny he’s worth. Maiden thinks of learning to low-crawl himself at the boy’s age, nineteen or there abouts, in the army, basic training, under concertina wire, fake rounds fired overheard and only sporadically. Nothing nearly so dangerous at 4160. The Red Hat hasn’t thrown the first chunk of coal up onto the belt, but Maiden does not reprimand. The boy is scared. Maiden lets him prattle on.

“Got an aunt over here in Grundy,” the kid says. “Reckon we might be up under her house?”

Maiden doesn’t answer. Says only again, “Watch it there now.”

“Hard to say, I guess. Never know though. Could be we are. Right up under Jimmy’s old room. Jimmy’s gone off to Beckley. We got people there. Know anybody in Beckley? I knew this one girl from War, nearby you know, and buddy I’m telling you she was abou–.”

And then, just like that, Maiden sees things happen twice before his eyes. One version takes place quick. In an instant, he sees the Red Hat stretch forward with one arm, his head buried into the earth. Then he bows up for leverage to push off again. And just as he pitches back on one knee, he arches his spine and the wet strap of his mining belt draws too near the 4160 and sparks. “Oh, Lord!” the boy cries. “Oh, Lord! Oh, Lord! Oh, Lord! Oh, Lord!” Over and over and over while Maiden screams back down through the shaft that a man has gotten tangled up in the wire. “Kill the switch!” Maiden screams. “Cut the goddamn juice! A man’s hit! A man’s hit! Good, Jesus, a man’s hit!”

“Oh, Lord! Oh, Lord! Oh, Lord!” the Red Hat seems to say, even though he is a puddle of flesh, melting like cheese in the damp but smelling of meat. Maiden knows he’s dead, but the kid keeps talking and Maiden just lies there, waiting helplessly as he was taught to do in miners’ school. He does not extend a hand. He doesn’t rush to the boy’s side, though the urge to is overpowering and Maiden just screams his guts out and cries for God in heaven to have mercy. He’s just a kid. Nineteen. Twenty at most. A big, gangly-legged kid whose knee caps have been blown off. “Jesus! Oh, Jesus! Hurry the fuck up down there!” Maiden calls again and again before the power is thrown and the Red Hat stops chattering.

~

In the other version, Maiden had seen a ghost behind the Red Hat. Some kind of phantom. A wisp or something. It was blurry but distinct enough that Maiden had fixed his gaze upon it while the kid had talked on and on about his cousin Jimmy going off to Beckley. Maiden’s wife begs him every night to quit. Number Six is about to shut down soon anyway, she tells him. When Maiden dons his carbide light and packs his dinner bucket with water and leftovers, she resorts to threats, name-calling. Maiden, you sonofabitch! Maiden! Maiden! He lets her speak her peace. Goes on to work. Someone has to run the scoop.

Today they are coming back up the middle, robbing all the pillars. Number Six will chase them tunnel by tunnel as they pull timbers and wait for the roof to collapse one room at a time so they can mine the fall. That’s money standing there, supporting the roof, and the company wants every square inch.

The Red Hat is not the first man Maiden has known about dying, nor the only one he’s witnessed firsthand. Parmelai Cline was caught between two cars on the tipple of a breaker. Clarence Price was killed by a rush of slush when water forced it out the gangway. Julius Reed was tamping a hole when powder in the tunnel exploded. During miners’ training, Maiden heard about men suffocating when they walked into pockets of gas, being struck by frozen slags of culm or being smothered by a rush of dirt working at the culm bank. Men had been run over by loaders, crushed by cave-ins when ribs gave way. They’d been burned, mangled by machinery, and electrocuted like Charlie, the young Red Hat.

When Maiden runs the scoop back through the shaft where the boy died, he wonders about the aunt’s house in Grundy and whether or not they had indeed been somewhere under it when the kid had gotten caught up in the wire. It’s risky, thinking about the dead so soon, if old wives’ tales are to be believed. Bad luck. Better if he thinks of something else, just in case, but the Red Hat consumes his thoughts. Goose What-was-his-name? And then the boy melting like a Popsicle before him. He wonders where the boy’s aunt might’ve been standing. Had she felt something, deep in the earth, some pull on her like a dowsing stick drawn by a vein of ground water?

The robbers begin taking out a few of the timbers as Maiden waits near the other room with the scoop and watches. Those remaining start to buckle under the weight of the roof, but the process isn’t as fast as he expects. The roof does not cave in immediately in order for them to load the fallen coal onto Maiden’s scoop and send it out into the yard. The robbers go one timber at a time, striking with their hammers, prying and shoving on each one until it kicks loose from the floor and the weight of the rock above their heads is redistributed to the others still standing. It’s a game of Russian roulette, no telling when the roof will fall, so they work slowly, pulling one timber and then watching, listening as the other supports begin to splinter and crack in the dark around them. There is nervous energy between the robbers. They talk casually together, laugh loudly, estimating if they should maybe pull another one. Watching by the dim torch of his carbide light becomes unbearable for Maiden. He can feel the weight pressing down on them, inch by inch, timbers slowly splintering and buckling all around, but still the roof is content to hold.

“Son-of-a-bitch,” one of the robbers says. “She ain’t budging. Run the scoop up here, hoss, and let’s see if we can shake this bitch loose.”

Maiden realizes he is being addressed, but still he hesitates. “What’s that?”

“Run the scoop this a’way and see if it don’t shake the ground just enough.”

All four of the men, including Maiden, are working on their stomachs. Whenever the roof does decide to fall, they won’t be able to run. The robbers can’t risk pulling out another timber. Maiden watches as they make their way toward him to the other room, a safe distance away from the shattering timbers. At least he has the scoop, which might be fast enough.

He wedges himself into the machine and drives forward cautiously as the robbers tell him how to proceed.

“Tap on that one right there,” says Arbury Massey. “Easy ought to do it, and then hightail it back.”

Goose Gossage was the ball player’s name, Maiden remembers. And then he is caught by a feeling of being drawn upward. He hears a low growl of thunder and looks around to see that the cap boards have begun to twist and rip. The watery contents of his stomach seem to rise like a wave in his diaphragm. But it’s not only that; the blood in his heart and veins pools at the top of his head, in both arms and legs.

The Red Hat’s aunt is standing directly over him, he realizes. Maiden closes his eyelids, lifts his face, and as the tears well in his eyes, they too are drawn up in streaks that wash the coal dust from his temples and over his forehead. The woman kneels to the floor and places her hand, just there, on his cheek. And then the earth rains down.

Sheryl Monks is the author of Monsters in Appalachia, published by Vandalia Press, an imprint of West Virginia University Press. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Queens University of Charlotte. Sheryl’s stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Electric Literature, The Butter, The Greensboro Review, storySouth, Regarding Arts and Letters, Night Train, and other journals, and in the anthologies Surreal South: Ghosts and Monsters and Eyes Glowing at the Edge of the Woods: Contemporary West Virginia Fiction and Poetry, among others. She works for a peer-reviewed medical journal and edits the online literary magazine Change Seven. Visit her online at www.sherylmonks.com.

“Robbing Pillars” is excerpted from Monsters in Appalachia (Vandalia Press/WVU Press, 2016) and first appeared in Split Lip Magazine. It appears here, courtesy of the author.